Little Round Top. May 4, 2017. The hillside has been restored to its July 2, 1863 appearance.

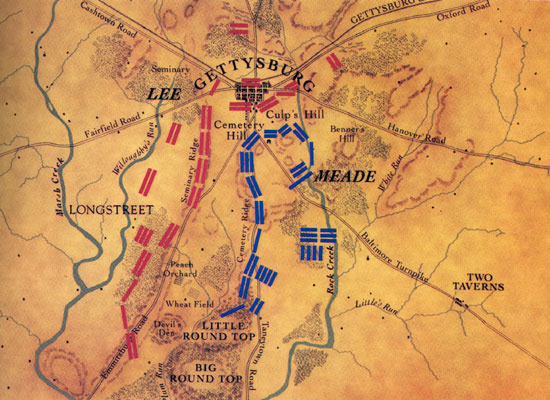

On July 1, 1863 the Army of Northern Virginia commanded by Robert E. Lee had engaged elements of the Army of Potomac west of the Pennsylvania college-town of Gettysburg, eighty miles northwest of Washington City. By nightfall the confederates had driven the federals back through the town into defensive positions on a series of hills and ridges stretching southward.

Overnight the federals dug in. By morning the Union line resembled an inverted fishhook. Its eye dangled perilously to the south, around a pair of small hills known as the Round Tops.

Map of the disposition of the Union and Confederate armies at Gettysburg. July 2, 1863

Map of the disposition of the Union and Confederate armies at Gettysburg. July 2, 1863

While Lee seemed to concentrate his attacks to the north at Cemetery Ridge and Culp’s Hill, Longstreet’s Division attempted to repeat Jackson’s victorious maneuver at Chancellorsville two months prior, by embarking on a circuitous flank-march concealed by Seminary Ridge. Lee’s tidy left-right punch was distracted by Sickles’s corps advance into a peach orchard half a mile west of the federal lines. Sickles lost a leg. His troops were driven back to their starting-points, but the fighting cost Lee a modicum of momentum. As a former member of the elite Corps of Topographical Engineers, keenly aware that his talented opponent possessed an uncanny sense of terrain, federal commander George Meade dispatched another Topog—G. K. Warren to reconnoitre the ground around Meade’s exposed left flank.

Gouvernor Kemble Warren. (1830-1852)

View from Little Round Top. May 4, 2017

Surveying the fields and tree-lines from the summit of Little Round Top, Warren confirmed its vulnerability. Strong Vincent’s Brigade was rushed south to its defense. Rocks were hastily piled into makeshift breastworks on the slopes and summit. Posted on the far left of Vincent’s line was the Twentieth Maine, commanded by Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain who before the war had taught rhetoric at Bowdoin College.

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (1828-1914)

Repulsing furious confederate attacks, running low on ammunition, Chamberlain ordered his men to fix bayonets and charge. The vertiginous slope was wooded and littered with bounders. As the guns fell silent and the smoke cleared, a regiment of Alabamians beheld hundreds of Down-Easters leaping from boulder to bounder, rushing downhill at them with sharp, naked steel. Many broke and ran. Others threw down their weapons. No further attempts were made by confederates to take the position. Many historians credit Chamberlain’s quick thinking with the salvation of the federal army on the second day of fighting at Gettysburg. Eleven months later Chamberlain was seriously wounded in front of Petersburg. During his long convalescence Chamberlain traveled with his wife, back to Little Round Top. Twenty-five years later, veterans gathered to dedicate a monument to the Twentieth Maine. A modest block of Maine granite was unveiled on October 3, 1889, at very spot where the regimental colors had stood on July 2, 1863. During the ceremony Chamberlain rose to address his comrades in arms.

“In great deeds, something abides. On great fields, something stays. Forms change and pass; bodies disappear; but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls… generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field, to ponder and dream; and lo! the shadow of a mighty presence shall wrap them in its bosom, and the power of the vision pass into their souls.”

Kathie at Little Round Top. May 4, 2017

Kathie and I visited Little Round Top on May 4, 2017. Over the past ten years the National Park Service has been restoring the battlefield to the same configuration of fields, tree-lines and woodlots that existed on July 1-3, 1863. The removal of the scrubby tangle of brush, briars and vines that had clung to the hillside for more than a century revealed the haphazard defenses assembled by Vincent’s Brigade just before they were stuck by Longstreet’s relentless flank-attack. These physical memories of bloody conflict; earthworks borne of mortal necessity are far more compelling than stone and bronze memorials.

Breastworks on Little Round Top erected by Vincent’s Brigade. July 2, 1862

Fanciful depiction of the breastworks at Little Round Top from Frank Leslie’s Newspaper.

I have visited Gettysburg National Military Park more times than I can remember. Among hundreds of markers, statues and Beaux-Arts baubles scattered across the battlefield, none possesses greater modesty and dignity than that humble grey block, its capstone like the roof of a fisherman’s hut. The means were on hand, but not the desire to commission a weeping angel, or soldier swinging a musket.

To Yankee fishermen, sawyers, lumberjacks, clerks and professors who had suffered and survived. who had seen friends torn apart by volley-fire, or perishing with fevers, there was no point in glorifying what they achieved. It was enough to say we stood here, fought and bled, and did what needed to be done.

Twentieth Maine Monument, Gettysburg National Battlefield. Dedicated October 3, 1889.

Dulce et Decorum est pro Patria Mori

Follow Sketchbook Traveler on Facebook, Linkedin, Twitter and Instagram.

Peruse previous posts here. Dispatches #1-70. April 1-June 8, 2020.