Drifting through the Francis Picabia show at the Museum of Modern Art, visitors paused to read wall-texts and view the works through their mobile devices. I might have scoffed at what seemed like inattention or distraction twenty years ago. “Pay attention! Look at the work”, a voice in my head would have admonished, “This is a museum, not an amusement park!”

Visiting the 1996 Picasso Portraits exhibition, an elderly couple reminiscent of Billy Crystal and Carol Kane in The Princess Bride gripped their ear-paddles as they moved from work to work, listening to the audio guide. The husband, who moved through the show a few pieces ahead of his wife, turned, pulled on her sleeve and said,

“Come here! Look at this one.”

She swatted him away.

“Leave me alone,” she shot back, “I’m watching this one now.”

It struck me at the time that for many people visiting a museum was entertainment, a different form of television. Museums in the past twenty years have redefined the realm of infotainment. Half a century ago museums were cathedrals of culture—vast, hushed spaces through which handfuls of the reverent might go to ponder masterpieces. The transformation of museums into meeting-places, food-courts and party-shacks has been sharply criticized, but blending the agora with the acropolis is not stooping to popular culture, but reconnecting with it. The word museum means dwelling-place of the Muse—a place from whence inspiration might be drawn. Guiding the creation of the British Museum, for example, was the necessity to gather together under one roof the greatest achievements of civilization—arts and technology, which subsequently were celebrated by international expositions. Musee du Louvre was created by inviting the general public into a former palace, to feast on culture once reserved for a privileged few. South Kensington Museum—now the V&A, was conceived in part as a place of learning, where practitioners of certain crafts might be inspired to improve their own work by studying examples of excellence in the decorative arts.

Today’s museums must appeal to a broader demographic partly out of financial necessity.

One former museum director told me that entertainment value is a concern. For this reason, art and history museums have been looking to science museums for inspiration. Smithsonian Air and Space Museum’s spectacular record of audience engagement has for many years been a model for other museums seeking to build attendance. If a successful science museum needs a cafeteria, planetarium and a dinosaur, a viable art museum needs a restaurant, an event-space and a sculpture garden. Both need board members committed to sustained giving and fundraising. A patron might expect generosity to buy authority in program and exhibition planning, like the studio mogul who puts his mistress in a movie he produced. The job of curators today is not just to organize shows, but to deliver visitor experience.

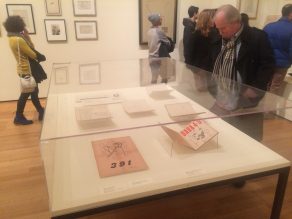

A continuous screening of Entr’acte, the 1924 film by Rene Clair, art-direction and sets by Picabia accentuated a refreshing promiscuity of media and form which the artist embraced. The ubiquity of vitrines displaying books and other material that once would have been deemed too inferior for a major retrospective underscored the diversity of his creative output. One tends to forget that Picabia’s early pictures are quite large, in contrast to Picasso and Braque’s early Cubist pictures. Standing off to the side of one of these paintings, seven or eight people gathered in a cluster to read the tombstone label. A similar number stood in front of the canvas, engaged in the slow, familiar dance of slipping sideways ahead and behind one another to take in the whole painting, and then drifting away to gaze at their phones, exchange a glance with someone across the room, glimpse a movie star pretending to not notice being noticed and then moving on to the next painting. Weaving my way through the crowd, I found an unobstructed view of La Source, 1912, and noticed some text on the wall underneath, directing viewers to become listeners by accessing a musical accompaniment selected by WQXR’s Terrance McKnight.

Purist might sneer, but this is nothing new. Frederic Church encouraged viewers to bring opera-glasses to explore the details in Heart of the Andes. George Catlin traveled his Indian Gallery around the United States and Europe with a trove of artifacts and a Native American dance-troupe. Catlin lectured on his travels as a painted backdrop moved behind him, between two giant rollers hidden from view. My first encounter with Emanuel Leutze’s image of Washington Crossing the Delaware was in a sound and light show in a deconsecrated church at Washington Crossing State Park, Pennsylvania. After Sunday picnics, hide-and-seek and vexing frogs and other wildlife, my parents, siblings and I would take a seat. Lights dimmed, music swelled, red velvet curtain parted and Washington’s head was framed in a circle of light. Speaking in a sonorous baritone the narrator unpacked a tale of defeat, retreat and hardship and how, with his army on the verge of melting away, Washington conceived a bold plan….

Sitting in the dark, enraptured with a tale that we all knew by heart, we beheld the great image emerge as its surface grew light, one section at a time. We gazed in wonder at the thrilling tableau, and then all was dark again. The curtains closed. The house lights came up and we all rose from our seats. I promised myself that one day I would see the real painting.

In 2012 Kathie and I attended the John Martin-Apocalypse exhibition at Tate Britain. Entering a side gallery, we found a seat on one of the stepped bench-rows installed to recreate the first showing of Martin’s famed triptych. The audience was seated. The room grew dark. A gaslight glow arose, flickering as a disembodied voice described the end of days, and the final judgment when the faithful are carried up to Heaven, with Christ on his throne.

The damned are cast into Hell. And there is the Great Whore of Babylon, conquerors and accursed, tumbling into the pit. And finally, cleansed of evil, the world is reborn as a bright new age begins, and suddenly, I remembered.

The following week we were back in New York. Kathie was speaking on a panel at the Salmagundi Club. One of the other presenters was Kevin Avery, now former curator of American art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. After giving him a report on the John Martin exhibition, I recounted my childhood memory, and commented on what a pleasure it is to have the original Leutze painting hanging in the Met. He smiled.

“Do you have any idea what happened to that picture you saw at Washington’s Crossing?”

“No idea,” I said. “For all I know it’s still there, behind those red velvet curtains.”

“No,” he said. “It’s gone. Long ago. But I can tell you where it is. You must have seen it.

It’s the centerpiece of the new American Wing. It’s hanging at the Met.”

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Linkedin

Linkedin