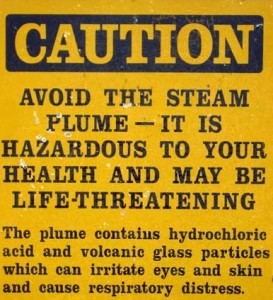

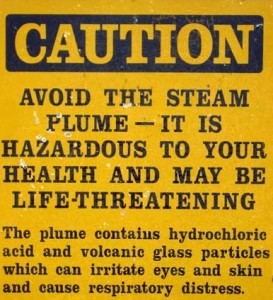

Pu’u Loa petroglyphs seem to be a modest collection of twenty thousand or so rock drawings. We later learned that these drawings are scattered up, down and across the fields of lava that had cascaded like fiery Niagaras from the escarpment rising up fifteen hundred feet to the north, onto the broad coastal shelf. Departing the dusty shoulder of the road, we followed a rough trail running seven tenths of a mile to east-northeast that terminated in a narrow, redwood viewing-platform elevated above the drawings, like temporary walkways that appear in Venice during Aqua Alta. I am always amazed at humanity’s undying faith in flip-flop footwear. Signs along the way warned of airborne dangers.

The petroglyphs consist of concentric circles, stylized figures along with rows and clusters of dots. One conventional theory is that the drawings were made as prayer rituals, although I would like to believe that some of them might have been made for fun—indigenous graffiti like Pacific War Kilroys. Differing from indigenous rock art found on the mainland in their intimacy, they seemed to present a collection of individual images rather than the pictorial narratives one find in Anasazi rock-art.

The precise meaning is lost. Perhaps they were measuring time or invoking the gods. Since the abolition of the old religion in 1819, the ability to interpret such images has been lost. On a more positive note, the Hawaiian language is alive and well, taught in many schools not only to natives but also to blue-eyed Haoles.

As we made our way back to the road a uniformed park ranger marched in the direction from whence we had come, shadowed by videographer and a soundman. As we crossed Chain of Craters Road to get to our car a stout lady with a southern accent descended from a large SUV. Oh no, she said. I’m not walking out there in these shoes. We ascended by the same road we had arrived, climbing quickly from the jagged barrenness of the plain behind us, the road traversing the ridgeline, winding its was upward into the dense cloud forest.

We arrived at Kilauea Military Camp (KMC), which I believe had been built for use by the Civilian Conservation Corps before being handed over to the army during the Second World War. Since it decommissioning as an active post, it has served as a modest resort for veterans, military personnel and their families. How the university had managed to billet us there is a mystery to me.

Michael and the crowd from the summer institute had yet to arrive. I marched up to reception and in my best military-speak informed the person manning the front desk that we had arrived and hoped to occupy our quarters. Papers were signed, keys were surrendered and I was given a map that directed us to a single story clapboard building located on the margins of the camp, with a canopied outdoor cooking area with picnic tables twenty yards from the building. Like all other buildings in the compound, the exterior was painted a kind of desert tan.

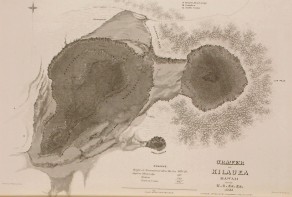

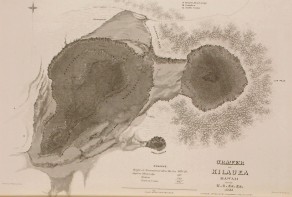

Our room was the only room with a private bath en suite. The other rooms had either twin or queen sized beds with shared bathrooms intervening. A large kitchen and contiguous living room divided our quarters from the rest. Kathie took a nap while I perused the chapter on Hawaiian Volcanoes National Park in our waggish Big Island guidebook. Of greater interest to me was an account of the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-42, under Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, which conducted a survey of the crater at Kilaeua in the winter of 1840, during which a member of the party was surprised and nearly killed by a sudden rise in the lava pool of Halema’uma’u, the smaller and most active crater within the caldera. Several artists accompanied the expedition, including Titian Ramsay Peale II, whose paintings of the crater have become canonical images.

Stories abound of hikers defying posted warnings against going off trail and breaking through a thin crust into lava flowing beneath it, or into plunging into deep, steaming crevasses. One tale alleges that a young female ranger, new to the park, had descended one of the steam vents with a male friend, to use it as a kind of sauna. She quickly succumbed to the heat. When her companion returned with help, she had been poached to a turn. We were told that this mishap occurred in one of the steaming pits in the meadows between the park entrance and KMC. Trails that visit these vents are well marked with cautionary signage.

One by one, members of the summer institute arrived, which included several instructors and about a dozen students; some from the university, two women from Canada and a few more from other parts of the Big Island. An unofficial member of the party was Denver artist Judy Gardner, who was renting a rustic cabin down the mountain in Puna for a few weeks.

Night fell. As dinner was being prepared a number of us boarded a ten-passenger van and were driven to the Jaggar Museum by Mike Marshall, who struggled in vain to extinguish the dome light. All that was missing from the ride to the rim of the caldera were commuters playing with their smartphones or reading the newspaper.

Crowding the railing along the paved observation deck, sightseers looked at the glowing cloud rising about the fiery ellipse of Halema’uma’u. Arriving with a video crew and floodlights, an Asian family pushed their way through the crowd to the barrier and then demonstrated no talent or dignity as stars in their own reality television show. Selfie-sticks were ubiquitous vexations, like umbrellas on a rainy day in Manhattan. People shouted nonsense at one another. A few bold souls had jumped the barrier to get a downward look into the vast pit. I was disappointed to find ogling the volcano the same collection of humanity one finds daily, herded into Times Square, Place Saint-Michel, Piazza San Marco, Machu Picchu and Disneyland.

One of the institute instructors, landscape painter Moses Kealamakia Jr. explained that locally Hawaiian describe the opening with the colloquial name of Lua’Pele, or Pele’s Hole. Pele, a maternal deity, is the indigenous goddess of fire who embodies volcanic activity that created the island, and continues to increase it. The name appears on the right side of a map produced by the Wilkes Expedition.

In the Hawaiian language lua can also just be a pit, such as the pit-roast or Lua’u.

Moses explained that among its multiple meanings, lua also translates as feces, which is why public toilets around the island are known as lua—a usage that combined two different meanings in one. I wondered aloud if the word was perhaps the root of loo—British slang for rest room. Moses cautioned me against assigning the word too much scatological meaning. Kuae’Pele, he explained, is the literal word for Pele’s feces, specifically the sulfurous deposits (brimstone) around the rim of Halema’uma’u and the odor arising from them. He marched off with a small coterie of students to explore if the trail circling the rim was open, presumably to scout motifs for a post-prandial plein-air painting session. The rest of use piled back into the rented van and returned to KMC.