Cusco, Peru. August 2, 2014

Retrieving our luggage, we passed through the arrivals hall and were met at curbside by a young man and a driver who delivered us to Hotel El Dorado San Agustin on Avenida del Sol, a few blocks off the Plaza de las Armas. The colonial-style building rose about five or six stories above the narrow two-way street, with a white-stuccoed façade, with large plate glass windows and a heavy wooden door. In contrast the interior was entirely modern. The glass elevator ran up and down a glazed shaft at the rear of the modest, sky-lit atrium lobby. Arriving guests were presented with a cup of Mate tea while the bellman sorted out a conveyance to lug baggage up to the rooms. Neither Kathie nor I were particularly worried about the altitude. In the past, both of us had spent considerable time at high altitudes. We knew enough to exercise caution, but as we settled in to what we expected to be a quiet day, a call from the desk informed us that a tour was waiting for us outside. Slamming another cup of coca tea, we climbed into the shuttle. Our guide rose and stood at the head of the aisle. Speaking into a mike he announced that we were embarking on a five-hour tour of the sights and monuments of Lima.

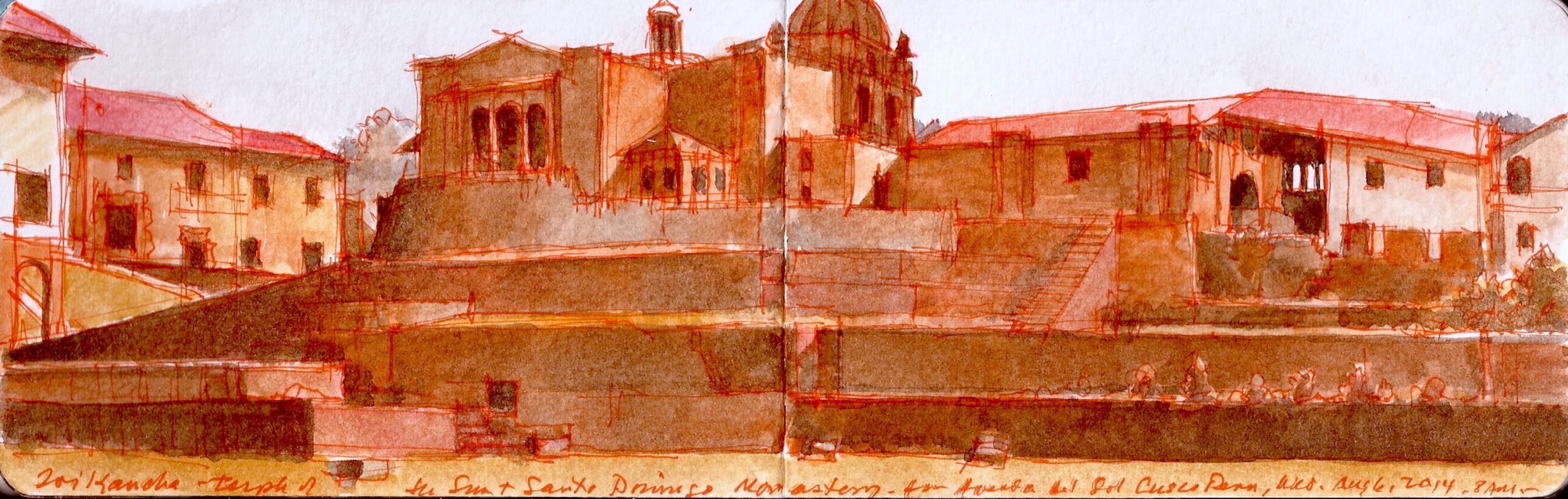

We got underway and stopped no more than five or six blocks away from the hotel, at the main Cathedral on Plaza de las Armas. The massive complex had been destroyed on several occasions by earthquake and rebuilt, each time with extensive modifications. Today its ornate facade is framed by a pair of towers. A small done rises above the rear of the main building. Our guide was named Ariel—a dark-skinned, compact, athletic man, of around sixty years of age. In his monologue he declared that his mother tongue was Quechua. Spanish is his second language, and English is his third. He works as a soccer coach, and when time allows, trains to become a native healer, a medicine man.

As a child he was taught the use of herbs, and how to identify them in the wild. As we descended from the bus and approached the cathedral, he explained that being a healer was about helping people toward physical and spiritual health. The Inca religion, he explained, was not just sun worship. It revered the order and power of nature. The sun was its most visible and powerful manifestation. The sun, and all of creation was the work of the Creator—the Supreme Being, called Pachacamac, which in many ways resembled the Jewish, Christian and Muslim God. Many Indios—the indigenous peoples of Peru—continue to observe Inca ritual, and at the same time practice devout Catholicism. I shared with him how the peoples of the Rio Grande pueblos divide their scared observances between the Catholic Church and the Kiva, and how the Sipapu—a small opening in the circular wall of the kiva—provides a portal between the world of mortals to that of the spirits. He seemed quite taken with this information and wrote down a few notes. We joined other tour groups clustered around the side door, waiting to be admitted.

Some guides carried long poles to which were affixed rainbow flags representing not Gay Pride but the banner of the Tawantinsuyu, or Inca Empire. The historical standard of the Inca (Emperor) had been a long vertical plume divided into bands the colors of the spectrum, plus a band of white or pale blue. The revival of Quechua and indigenous culture required a new symbol. In 1973, Raul Montesinos Espejo unfurled the new Inca banner to celebrate the silver anniversary of his radio station. The city of Cusco adopted it as its official standard five years later; the same year the now familiar Gay Pride flag appeared in San Francisco.

The cathedral is entered through great doors opening onto a vestibule in which two small doors open to the left and right. Waiting outside may have been a dozen or more groups creating a human logjam that would have made New York straphangers feel right at home. Moving from the bright, raking sunlight at nearly twelve thousand feet, into the cool, lofty interior, we beheld an ornate, gilded altarpiece, illuminated in soft golden radiance. Cool light filtered through clerestory windows in the choir, scattering the sculptures with pale blue highlights.

Our group slid into the first three or four rows of the transept. An attractive young woman from the tour company passed out ear buds wired to small receivers attached to lanyards. I noticed Ariel speaking into a rock-star chin-mike. Slipping the cord over my head and adjusting the receiver, I finally got the audio to work.

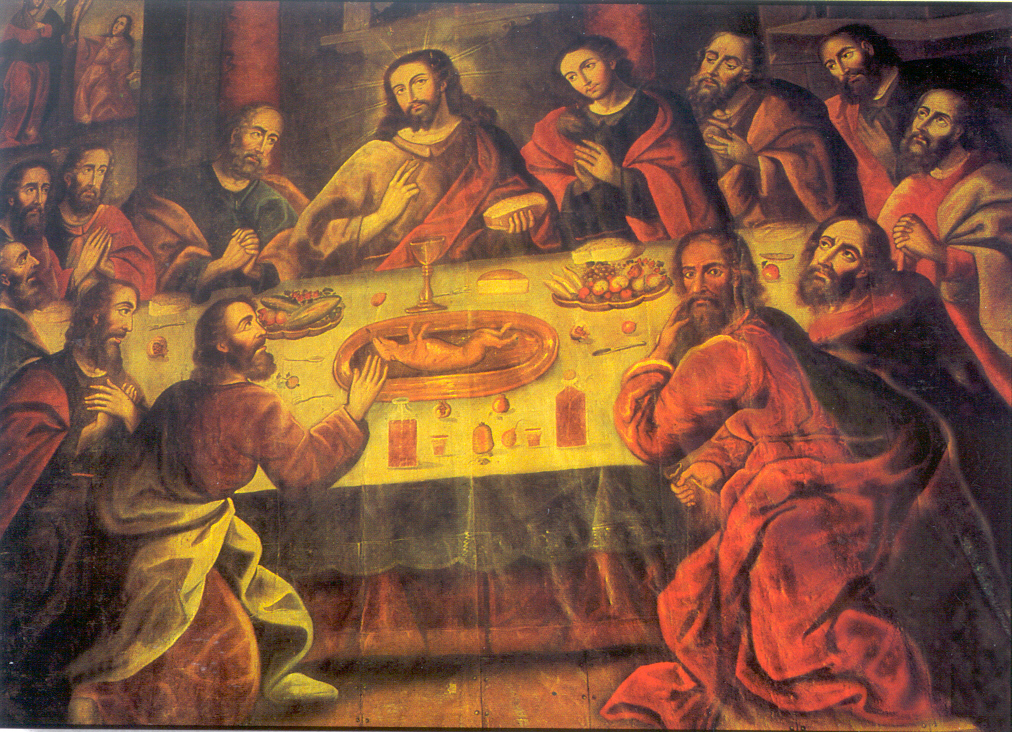

He explained that the chapel was one of the oldest parts of the complex, and that the altarpiece had been wrought in the Andean Baroque Churriguresque style by local artisans working in cedar. Following him out of the chapel and into the central nave, we visited a concatenation of smaller side chapels. An early colonial painting of the Last Supper showed Jesus and his disciples dining on Cuy, or guinea pig—a local delicacy. I was reminded of a Giottesco fresco in the Sanctuary of Saints Vittorio and Colona just outside of Feltre, near the base of Monte Grappa in northern Italy. At that Seder, the daily special was crawfish, which still abound in the Piave River and its tributaries.  fires rage through, roof tiles tumbling into gaping black holes. states that the destruction abated when El Señor de los Tremblores—a sculpture depicting a dark-skinned Jesus on the Cross—was displayed in the Plaza de las Armas. Believed to protect the city, the crucifix is paraded annually through the streets of Lima in a ritual that blends Christian and Inca traditions. Ariel explains that prior to the conquest, the mummies of past monarchs were carried through the Inca capital, renewing the bond between these semi-divine rulers and their people.

fires rage through, roof tiles tumbling into gaping black holes. states that the destruction abated when El Señor de los Tremblores—a sculpture depicting a dark-skinned Jesus on the Cross—was displayed in the Plaza de las Armas. Believed to protect the city, the crucifix is paraded annually through the streets of Lima in a ritual that blends Christian and Inca traditions. Ariel explains that prior to the conquest, the mummies of past monarchs were carried through the Inca capital, renewing the bond between these semi-divine rulers and their people.

The black Jesus may have acquired it coloring by exposure to incense smoke and candle-soot, but oral tradition claims that it was made in Spain at the order of Philip II, who specified that the skin of Jesus be the same color as the Cusqueños. Ariel dismissed this as Spanish propaganda, claiming that another version of the story states that it was carved by a local artisan or Incan descent. Spanish architecture has vertical walls, Ariel explained, which renders it susceptible to destruction by frequent earthquakes that strike Cusco, whereas Incan architecture is constructed with sloping walls, narrowing slightly from bottom to top. There are no square angles in Incan architecture, and because the stones are fitted together without mortar, they are mobile during tremors. When the seismic event abates, they return to their original place in the masonry.

Here Ariel began to reveal to us his fierce toward Spain and the crimes committed by its soldiers, priests and political leaders against the Tawantinsuyu. He admitted that his ancestors had belonged to one of the groups who sided with the Spaniards against Athahualpa, and later against Manco Capac and Tupac Amaru, the last Inca emperors.

“They killed many of us”, said our guide, “but they could not kill our culture. We have survived, and our culture is alive and well in spite of the Spanish.”

We learned that the cathedral complex had grown from first church in Cusco, established during the conquest by a Dominican Brother named Fra Vicente Valverde, who is today vilified along with Francisco Pizarro and his brothers for his greed, and the brutality he visited upon the indigenous people. Having fled Lima following the assassination of Francisco Pizarro, this cruel, ambitious priest was infortutiously waylaid off the coast of Ecuador by angry locals. As punishment for his arrogance and cupidity, vengeful Indios on Halloween 1541 forced Bishop Valverde to drink molten gold before they flayed, slaughtered, cooked and devoured him.

RETURN TO: James Lancel McElhinney BLOGPOSTS

NOW AVAILABLE. Order your copy HERE

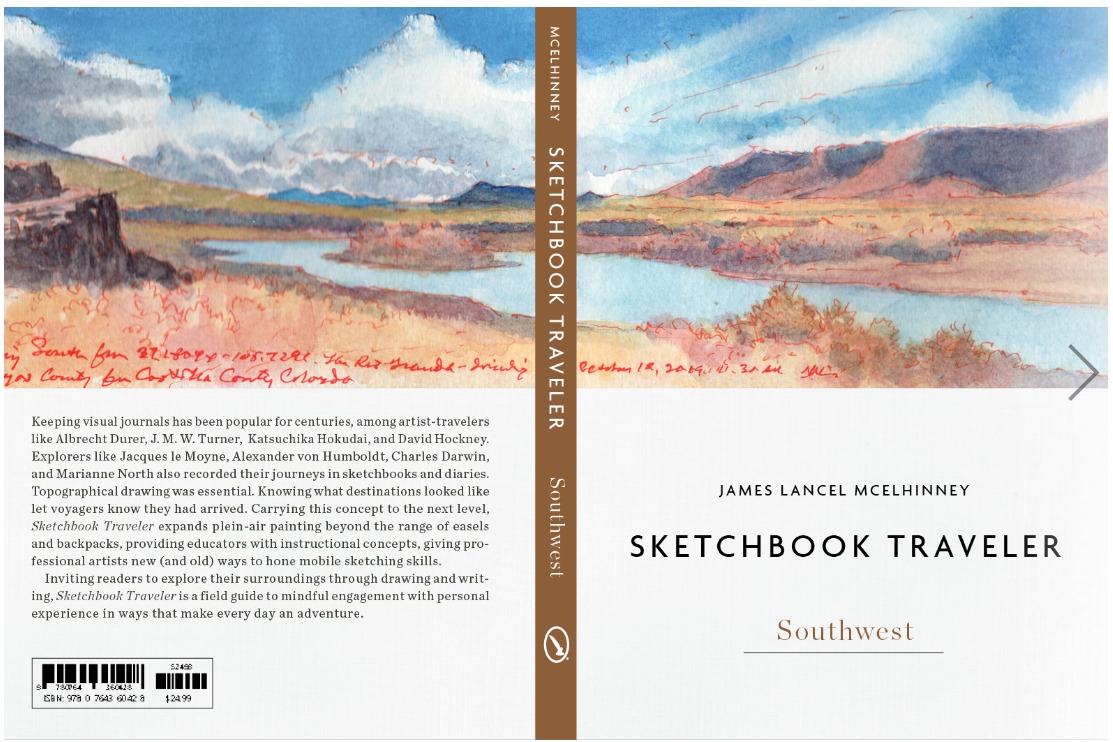

ALSO CURRENTLY AVAILABLE:SKETCHBOOK TRAVELER by James L. McElhinney (c) 2020. Schiffer Publishing).

Also of interest:

Order your copy of the book here: LINK

Order your copy of the book here: LINK

For information about Needlewatcher Editions, write to editions@needlewatcher.com

Needlewatcher Editions. PO Box 233. Essex, New York. 12936-0233. (347) 266-5652