PENMANSHIP AND NUKES: A LOVE STORY

James Lancel McElhinney © 2014

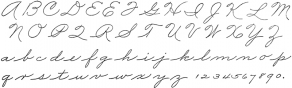

Recent articles in the New York Times and other news feeds revealed that many K12 school districts are doing away with penmanship in favor of keyboarding. The pet canary in the educational coal mine stopped singing years ago and is now dust and feathers, proving once and for all that very smart people can do extremely stupid things.

This latest stroke of curricular folly is the brainchild of highly educated but visually illiterate decision-makers, whose educational reforms are delivered by compliant teacher-corps of cowering jobholders to willing victims and their clueless parents.

It is pointless to spill more ink trying to argue how unrelated activities can reinforce learning or enhance performance, such as singing the alphabet, or marking cadence with sea-shanties , keeping step with marching songs, or nursery rhymes as aides-de memoire.

Music reinforces math. Poetry and literature inspire eloquence. Dance and sport promote physical health. Drawing develops spatial reasoning, with penmanship being the most easily teachable form of drawing. As John Gadsby Chapman proclaimed on the title-page of his 1847 American Drawing Book. “Anyone that can learn to write can learn to draw.”

The genesis of computer games lies in the development of weapons-systems-simulations used to train pilots, astronauts and drone navigators.

At a family reunion several years ago, an avuncular family friend railed against the Naval Academy dropping its course in solar-celestial navigation in favor of teaching midshipmen refinements in the use of satellite-based global positioning technology. Uncle Bob was a graduate of Annapolis. The bulk of his career had been spent working for a certain three-letter agency headquartered in McLean, Virginia. He pointed out that without a senior chief who knew how to handle a sextant on board, a nuclear submarine would be running blind after its payload wiped out global positioning satellites within the event horizon of the blasts. The only way for the captain to determine where he was on the globe would require reading the stars to discern the right parallel, and reckoning longitude with an analog chronometer.

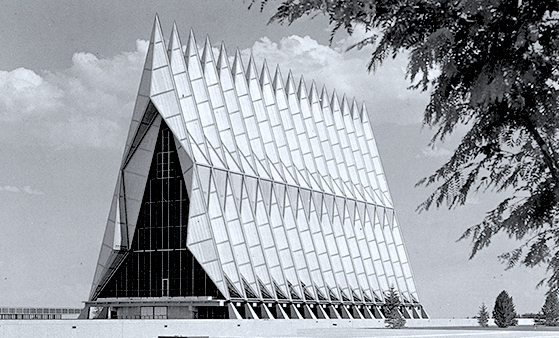

In 2001, I had been called in to pinch-hit for American Arts Quarterly senior editor Jim Cooper by delivering lectures on art at the U.S. Air Force Academy “National Leadership and Character Development Symposium”. During the midday break in the vast dining hall, I joined other speakers, cadets and senior Air Force officers around a lunch table. The conversation soon drifted from polite chatter about the menu to nuclear weapons deployment tactics. I was fascinated by the discussion that weighed blast altitudes against megatons, to disable electronics on the surface with an electromagnetic pulse generated by detonating thermonuclear weapons just outside the atmosphere, to minimize physical damage to built infrastructure on the earth’s surface. This conversation occurred a few years before drone technology and GPS devices was marketed for civilian use. Concerns were raised that some of the electronics upon which weapons-delivery aircraft depended would be disabled by nuclear explosions. Any Navy man could have piped up and reminded the table that because a large part of America’s nuclear arsenal is aboard submarines. No fly-boys need apply. Friendly rivalry between armed forces branches of service aside, it seems that one hand knows nothing about what the other one is doing. It is this kind of compartmentalized, task-to-outcomes thinking that now afflicts our educational system today.

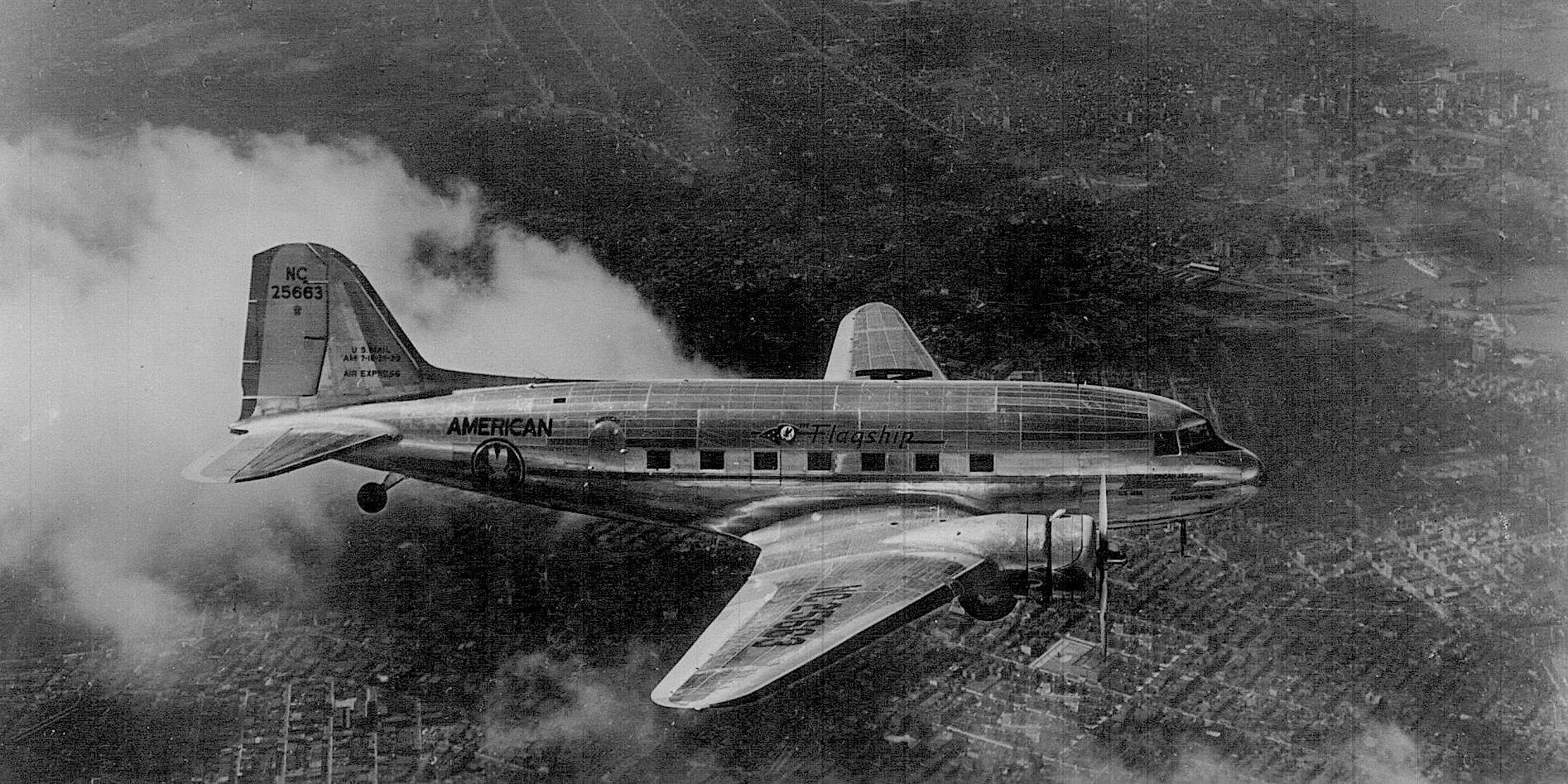

Shortly after VJ-Day, a young playwright named Arthur Miller was on a flight to Los Angeles, to deliver a screenplay he had written about the life of KIA war correspondent Ernie Pyle. Seated next to him on the plane was an engineer. Looking out the window at the desert lands below the man declared,

“You know, all that dry land could become a breadbasket. Below the desert lies one of the largest freshwater aquifers in the world.”

“But how do you get water to the surface?” Miller inquired.

“Nuclear explosives,” the engineer calmly replied.

“Wouldn’t that contaminate the water?”

“Oh that’s not my department.” The engineer replied.

Whatever skills one can learn in a flight simulator or with a X-Box are provisional, offering no guarantee that proficiency in virtual reality will be entirely applicable in physical environments.

In principle, manning the controls of a biplane or crossing the ocean in an open boat is the same as remote-piloting a drone or skippering a supertanker. Meanwhile, back at Annapolis, new classes of midshipmen are being taught to privilege their tools instead of developing a greater capacity for problem-solving traditional analog crises. In plausible battle scenarios, a nuclear detonation just outside the atmosphere could knock out every satellite within range of the blast, shutting down computers on the surfacet, including those on the sub that launched it. New tools do not render old skills obsolete. GPS, like computer keyboards, CADD and other new tools offer welcome conveniences but they have not relieved us of the necessity for us to be able to think for ourselves.

Dark days have overtaken the overseers of pre-college and higher education. As unwitting victims of the same faulty learning-systems they now direct, they fail to grasp that they have become part of the problem.

Cults of self-expression that arose during the 19th century threw the baby out with the bathwater. Spinning the history of drawing as indivualistic mark-making justified their existence, while inadvertently hijacking what once had been a widely-taught visual language into something reserved for poetic use. English is taught to everyone; not just those with literary ambitions. Math is required for all; not only future physicists or engineers. And yet drawing, which Horace Mann called “a moral force”, and “an essential industrial skill” is reserved (under the dubious rubric of “art”) for those professing artistic aspirations, and other seeking after-school “enrichment” programs.

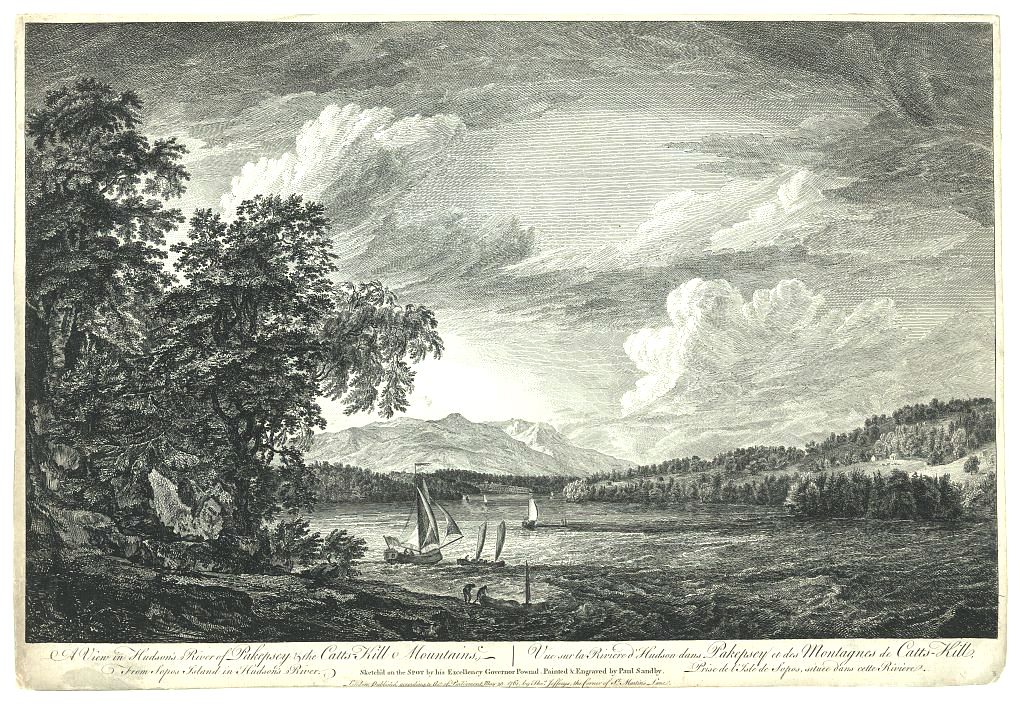

Many artists today are unaware that drawing was a required course at the military academies of Woolich, Mezieres and West Point. Not only were cadets expected to produce mechanical drawings and maps. They were taught to render topographical views with an artistic flair. Mastering the aesthetics of drawing was believed by the high command, to make keener observers of military draftsmen in ways that might serve them as explorers, and on the battlefield. Likewise, civilian education included drawing in its curricular core. Books were published for use in schools and at home, by autodidacts and classroom instruction. Drawing manuals written by Archibald Robertson, John Gadsby Chapman and John Ruskin were best sellers. Ruskin’s The Elements of Drawing remains in print today. Rembrandt Peale’s 1834 Graphics broke ground by mapping out a curriculum of drawing and penmanship, in the same course of study at Philadelphia’s Boys’ High School. It’s unlikely that today’s STEM-besotted educational system will fully embrace the alternative values of STEAM, for the simple reason that the financial aparatus of performance and reward favors bean-counting outcomes over expert evaluations. For this reason, the benefits of culturally enriched education will drift back into the realm of privileged learning, which in time will only serve to deepen socioeconomic divisions within our society. Should the unthinkable occur, and our civilization is devastated by nuclear warfare, survivors who can read the night sky, use flint and steel to build fires, possess the wherewithal to kill and butcher game, raise crops, and translate ideas into visual form, will fare better than those who cannot.