http://www.cooperandsmithgallery.com/#!jamesmcelhinney/c85b

All posts by James Lancel Mcelhinney

Hilo, Day Two: June 30, 2015

I awoke at 4:30 am and noticed the new tenants of the guitar shop loading dock, shot off a few emails and settled into reading a book about the big island. I always research new places I visit. On my first trip to the state of Hawai’i I was keenly aware of having been misled by tall tales of early contact with savage kingdoms and riveting performances by Jack Lord and Don Ho.

My goal was to be open to whatever I might find, and had become aware of protests against the construction of a massive new telescope on the summit of Mauna Kea, the Big Island’s highest peak at 13,796 feet above sea-level, which is regarded as sacred by indigenous Hawaiians. I saw a parallel between the contest over Mauna Kea and some of my earlier subjects like Civil War and Indian War battlefields. Years ago I had participated in a fundraising exhibition to protect the Big Mountain Reservation in Arizona. Throughout the course of our visit I became increasingly aware of how profound were the divisions within the community concerning the proposed Mauna Kea observatory. Almost nobody we met held a neutral position. Most were either for or against the plan with considerable passion, which I took as a warning to stay out of the fray.

As dawn broke, Hilo Bay stretched out like a sheet of beaten silver beneath rosy, clouded skies, a spectacle played out behind the electric glow of the Tesoro gas station at the corner of Ponahawai and Kamehameha. Kathie figured out how to make coffee in the room by inserting single–serve Melitta packets into a Keurig-like contraption. Neil the landlord later confessed that after he bought the machine, he could never find packets to fit it. Frustrated and maniacal about her coffee, Kathie wondered aloud why he hadn’t replaced it. One of these days, Neil replied. One of these days.

We wandered out into the street in search of breakfast. Paul’s café on the ground floor of the Pakalana building was open but had only three tables. Every one of them was full. An empty table stood outside the door on the sidewalk. We were told that there was a wait list and if we wanted to leave a name they would call us.

Seeing no one else waiting, we drifted off through the open-air market at the other end of Punahoa Street, past Reuben’s toward the center of town where we found the Surf Break Café.

The coffee was serviceable. The oatmeal was mixed with nuts and dried fruit and had an odd crunchy texture. I looked at my watch. Six hours.

In New York it would be two o’clock in the afternoon. Suddenly the lackadaisical notion of Hilo Time made sense. Whatever the clock said, the time is always now, at least most of the time.

Kathie returned to the Pakalana Inn while I proceeded to University of Hawai’i at Hilo to meet Mike Marshall and review our plans for the next two weeks.

I found him in building 395 on the community college campus. The art studios had been moved from the main campus, up the hill a mile to the west, while faculty were still expected to keep their office hours at the main campus. It seemed like a bit of a cockamamie arrangement but like at most public universities today, the arts at Hilo are fighting redundancy, and pressure to demonstrate specific vocational values for the undergraduate degrees they offer. Things in favor of the art department at Hilo is that it only offers a Bachelor of Arts degree, and it has a superb printmaking facility making it possible to argue that students coming out of the program have sufficient training to find tech work in fine art publishing, perhaps at places like Crown Point or Gemini G.E.L.

I was introduced to master printer Jonathan Goebel and given a quick tour of the facility before Mike and I loaded a few framed drawings into the blue Nissan and drove back into town to deliver the artwork to the Wailoa Center.

Prior to my arrival I had juried a national drawing exhibition that was scheduled to open at Wailoa on July 10th. It was the first time that I had juried a show online. Entries were submitted to a central collection point managed by WESTAF (Western States Art Federation) in Denver. Given a username and password I went online to make my selections. The process was vexing in the sense that one was forced to make decisions based on thumbnails and jpegs. I was asked to score my selections from one to five, but to make things simple I gave fives to all my selections.

The reason for this last minute delivery was that a state parks official had demanded that all images of nudity be removed from the show. On the surface it seemed like a cut and dried case of knuckleheaded philistinism, but as facts unfolded it became apparent to me that it was a bureaucratic maneuver calculated to undermine the facility. The apparatchik who banned several works that featured undraped bodies may have been a religious fundamentalist but whoever it was also worked for an agency that was not entirely happy about running an arts organization, and was looking for the vaguest excuse to repurpose the facility.

(To be continued)

Hilo Day One: June 29, 2015

Hilo Day One: June 29, 2015

Arriving in Honolulu after a ten-hour flight from Newark, we descended a mile to the south of Pearl Harbor. The Arizona Memorial’s white chopstick-rest profile was visible against the verdant margins of a turquoise cove. Debouching from the plane, our lungs filled with fresh air as we entered the terminal building, which was unencumbered by any measure of climate control and open to the free passage of breezes, birds and thankfully few insects. Cool sea breezes stirred the warm moist day as we trudged from our arrival gate to the opposite end of the terminal, where we boarded an inter-island flight to Hilo.

Passing over stretches of the Pacific we recognized the long form of Molokai, and the gourd-shaped contours of Maui before approaching the cliff-bound northern shores of the Big Island and the grassy Kohala highlands, before descending above the forests and farm-fields of the Hamakua Coast, crossing Hilo Bay and landing at the airport a few miles south of the town.

Greeting us was a diminutive Japanese woman holding a taxi-placard marked “Manthorne”. Draping orchid leis around our necks, she welcomed us to Hawai’i. We exchanged pleasantries and bowed to one another. I gave her a five-dollar bill.

Smiling, she hastened off to her next assignment. Kathie’s brother Jay had arranged for our welcome. A retired Coast Guard air/sea-rescue helicopter pilot, for several years he had been posted to Honolulu and grown fond of island customs.

Black clouds gathered above Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa, while seaward skies were clear and blue. The air was warmer and more humid than at Honolulu. Likewise the arrivals terminal in Hilo was open to the elements. We found the baggage claim located beneath what reminded me of a sprawling marquee—essentially a roof providing shelter from light rain but what seemed like little protection from the high winds that must accompany so many tropical storms that blow through the islands. As we dragged our bags off of the carousel, I saw Michael Marshall standing by the curb. He smiled in recognition, approached and festooned us with two more orchid leis. It seemed impossible that Mike and I had not laid eyes on one another for thirty-nine years. I handed him my iPad and asked him to take a few pictures of Kathie and me.

Following some minor confusion regarding the status of our rental car, Mike drove us to our quarters in downtown Hilo, where we deposited our luggage, and Kathie to unpack it. He gave me the quick motor tour of Hilo, which led us to an Enterprise car rental agency located on a highway strip at the edge of town. Papers were signed. We parted company and I drove the Pacific-blue Nissan back to the Pakalana Inn in the town center. Located on the second floor above a café, breakfast grill, ukulele shop, the inn was owner-run by a thin, vaguely hirsute, informal fellow named Neil. Four basic studio apartments can be had at the inn for the night or for the month, according to the requirements of Neil’s guests. The university used the Pakalana Inn as lodgings for new faculty members, visiting academics and the occasional reception. A groaning swamp cooler provided some comfort from the midday heat.

The room was equipped with a large wooden Roaring Twenties armoire, a large sofa, upholstered armchair, queen bed and contemporary café table, with chairs en suite. Neil cautioned us against leaving the bathroom door ajar. Unlike the windows in the main room, the bathroom was equipped with the leaky glass-louvered fenestration I recall in beach motels on my childhood holidays.

Ours was the corner room of a wood frame and corrugated steel building. The windows on one side of the building faced the loading dock of a guitar shop, and on the other the northern fringe of a memorial park that had been created when the City of Hilo decided not to rebuild a portion of the town that had been devastated by a tsunami in 1930.

As the guitar shop across the street closed for the day, I noticed a homeless Asian man unsling his backpack and make camp on the loading dock. He nodded to the storeowner, who nodded back, got in his car and drove away.

Famished, we discovered that on Monday nights Hilo restaurants that were open closed early. We dived into the nearest one we could find, descriptively named Reuben’s Mexican Food. A couple of watery Margaritas and decent meals later, we staggered back to the Pakalana and collapsed into bed.

The homeless man was there when we went to sleep, but in the morning a dirty woman and her dog asleep on the loading dock, had taken his place. Beside them, resting on its kickstand was a new, well-maintained bicycle.

I was reminded of the late Lester Johnson’s description of Bowery bums stirring from their slumbers like the dead stiffly returning to life, becoming limber, animated and alert until they found their way to a bottle of cheap wine, stupefaction and another sleep like death. And then the process would repeat itself. I wondered what stories unfold in Hilo during the wee hours of morning, of lost souls and night crawlers, which like vampires, vanish at daybreak.

Learning to See Anew: Priorities in Drawing and Education

LEARNING TO SEE ANEW: PRIORITIES IN DRAWING AND EDUCATION

A panel discussion held at the Art Students League of New York on Friday, February 13, 2015, featuring presenters Jeffrey Carr, Brian Curtis, Peter Kaniaris, Samuel Messer (respondent), John Rise, Flash Rosenberg and Peter Trippi.

INTRODUCTORY COMMENTS

James Lancel McElhinney, moderator

Art education is in the midst of a sea change. The BFA MFA culture in which many of us were trained will not be sustainable forever, aggravated in part by diminishing opportunities for K12 students to receive any kind of visual training at school.

Many colleges are universities are stepping away from studio education, which one might argue is not a bad thing given their performance record. Meanwhile flagship institutions like Yale School of Art, founded in 1869 and first led by John Ferguson Weir, whose brother Julian taught here at the League, or the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts continue to represent the highest standards of studio learning in accredited institutions of higher learning. Both institutions are represented today on this panel. Public universities that evolved from Land Grant college offered drawing at first as an industrial skill, but also to quote Horace Mann, as a “moral force”, necessary to the formation of a well-educated citizenry. Drawing and penmanship have been discarded by many schools in favor of keyboarding, a decision made by people who never enjoyed the benefits of Mann’s vision of universal education, and thus know not what they do. In 1834 Rembrandt Peale published Graphics, a manual of drawing and penmanship. In the introduction he observed that writing is drawing letters, while drawing is writing forms. On the title page of John Gadsby Chapman’s 1847 American Drawing Book is the exhortation that “anyone that can learn to write can learn to draw”. Massachusetts has vowed to maintain penmanship in its primary curricula, but many other states are doing away with it altogether. When Sony Imageworks announced at a SIGGRAF conference in Boston that it had secretly run a life drawing academy, followed by similar confessions by Pixar, Disney and other animation houses, many colleges and universities had to backpedal out of digital-privileging dismissals of traditional foundations subjects and resuscitate their drawing programs. The development of the Wacom tablet, iPad and Bluetooth stylus and new drawing software has created a tense parity between digital and analog drawing media. Many studio artists have yet to grasp the implications. Both offer different advantages, giving us more tools with which to draw. The later Bernie Chaet used to proclaim with emphasis, that drawing is not a technique! Nothing can be learned about Shakespeare by studying goose quills, or Hemingway by examining typewriters. Drawing is a language.

The question is how to teach it. Pre-college education requires everyone to study language and math, including people with no plans to become writers or physicists. Yet drawing is withheld to all but those who declare artistic ambitions. Everything in the man-made world and the built environment begins with a drawing. Thus with no understanding of drawing, how can one understand design, or how it shapes the world in which we live?

Today the Art Students league of New York is privileged to present a distinguished panel of speakers who will identify new priorities in drawing and education. We may not settle the matter today, but we may be able to set things in motion, in more useful directions.

EXCAVATIONS: 1980s URBAN LANDSCAPES

In 1982 I quit a teaching job at Skidmore College. It would not be the last time I fled the clutches of higher education. Together with Vicki Davila, whom I had recently married, we moved from Saratoga Springs to Philadelphia. Both of us had grown up in the Delaware Valley, and attended college at the Tyler School of Art. In many ways, it was a homecoming. We acquired a property in Queen Village. During its renovation we lived a mile to the north, on the 300 block of Brown Street in The Northern Liberties. Our apartment was situated on the top floor, with access to a small the rooftop deck, affording broad vistas of what was then a low-rise city. At the time, this now fashionable area was still quite rugged. Dilapidated buildings lined potholed streets inhabited by rough characters and seedy bars. The view from the rooftops offered a different kind of landscape. The sweeping arc of the Interstate highway rose up like a whale, from a sea of decaying architecture. The skyline was punctuated by billboards and the smokestacks. The heaving bulk of Shackamaxon power station lay beyond. Penn Treaty Park lay beside it on the right bank of the Delaware River. Here in 1682, William Penn negotiated the purchase of lands that later became The Keystone State from Lenni-Lenape Sachems. Saki-mauch-een-ing (Shackamaxon) was the Lenape equivalent of Westminster Abbey. The site was designed for the ceremonial investiture of Lenape chiefs, whom pacifist Quakers hoodwinked at that very place.

From 1982-83, my studio was located on the second floor of what had once been a Masonic Hall, across the Fairmount Avenue from the modest row house where in 1902, Larry Fine of Three Stooges fame had been born. My landlord was Robert Betty, who owned the building and operated Mangam Organ Company, on the ground floor. The atelier built and repaired traditional pipe organs. Philadelphia was , and remains famous or its music industry. Apart from its world-class orchestra, the city had been home to many Jazz greats like John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie and Billie Holiday. The pop music television show American Bandstand was first broadcast from Philadelphia.

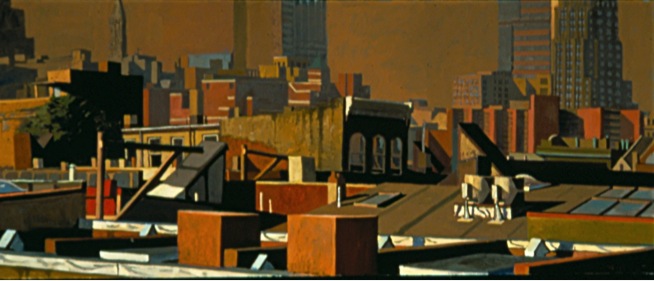

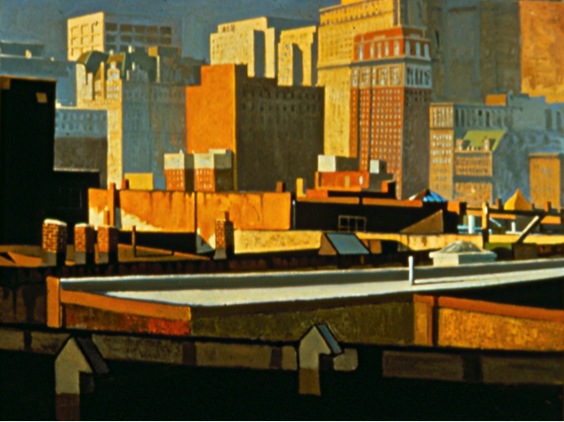

Oil sketches made from our Brown Street rooftop captured the visual syncopation of the city; its rhythmic geometry, character, and textures, played out on Northern Liberties rooftops. These later inspired a number of finished compositions, one of which was acquired by master violin maker William Moennig; the brother of actress Blythe Danner.

In 1983, we moved into our newly-renovated home; a former taxicab garage on Fulton Street in the Queen Village neighborhood of South Philly. Instead of peeling tarpaper, rusting cornices, crumbling chimneys and stucco falling in sheets of weathered bricks, the adjoining buildings hummed with new HVAC units. Raft-like, roof-decks floated in a lagoon of masonry. Gleaming skylights and television antennas broke the surface, stretching away to City Hall tower, crowned by Calder’s Billy Penn. To the east stood the the Benjamin Franklin Hotel and the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society, the first modernist building in the International Style, designed by Lacaze & Howe in 1932. Nearby was the spire of Saint Peter’s Episcopal Church, the graveyard of which holds the bones of Charles Willson Peale. In the distance was seen the hulking Customs House. These views developed into monumental compositions, drawing praise from the late Edmund Bacon, Philadelphia’s Robert Moses, whose impact on the city remains a matter of controversy.

Like many origin-myths, the genesis of this body of work did not follow a straight path. My interest had always been more keenly focused on the natural landscape. Cityscapes were convenient. On many days I might paint along Schuylkill Banks, or drive up the Delaware Valley to Bucks County. These were not my quotidien terrain. Nor at the time had I developed a coherent narrative, beyond my desire to work in a certain way.

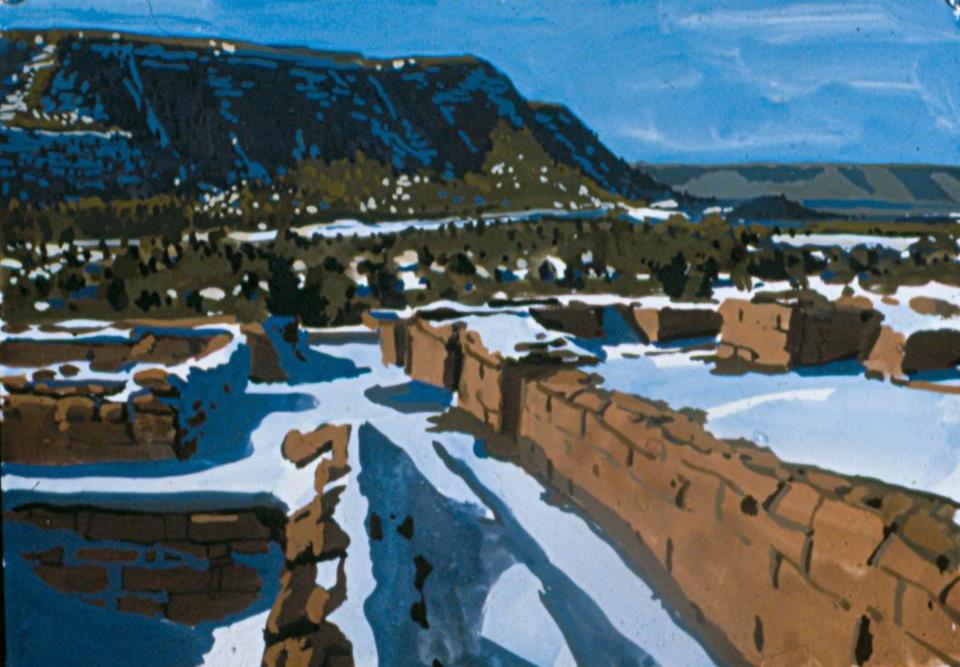

Vicki and I had gone to Santa Fe in 1982, to spend Christmas with her family. On many days, I would venture into the terrain, making sketchbook drawings, painting in gouache on location. The idea of painting in books had not yet come to me.

Excursions took me to Pecos, Cochiti Canyon, Black Mesa, Acoma, Chaco Canyon, Bandelier National Monument and the ruins of Pecos Pueblo. Covered in snow, these sites in winter can be desolate and haunting.

Returning to Philadelphia after the first of the year, I began a series of large scale paintings inspired by my work in the field.

I never copied my sketches, which gathered impressions that could be developed into durable memories upon which I could draw. Each studio foray failed to capture the specificity and spontaneity of my open-air works from New Mexico. It dawned on me that despite painting in New Mexico for nearly a month, my depictions of Southwest ruins and geology had been filtered through my familiarity with architectural forms and spaces, back home in the East. Within a few days, my large paintings of New Mexico had been transformed into views of Philadelphia. Suddenly, it all made sense.

The series of paintings that followed progressed for several years, yielding canvases that ranged in size from thirty by fifty inches, to six by eight feet. Several large drawings were produced at the same time, none of which survive.

The discovery for me was the unexpected randomness of the urban environment, which from the prospect of a rooftop could seem organic, like a coral-reef, or a field of pumpkins. Some effort might be exerted to maintain a coherent streetscape. The ever-present mayhem caused by automobiles, commercial signage, and the astonishing vicissitudes of personal taste challenge order at every turn.

Rooftops are different. These are realms of neglect and privacy. Living amongst the rooftops of Philadelphia, I beheld people engaged in quarrels, burglaries, police activity, barbecues, sunbathing and alfresco lovemaking. They felt secure–even invisible–on their own rooftop. Privacy often relies on the discretion of others.

LEARNING TO SEE ANEW: PRIORITIES IN DRAWING EDUCATION

Observational drawing is enjoying a revival. Renewed interest in visual expression is fueled by the proliferation of images of artwork on the Internet, the primacy of freehand drawing in the animation and game design industries, and the doggedness of the studio artist who daily measure their vision against a ready surface with burnt sticks. Drawing today is often taught under the heading of works on paper.

Can it be described as a materials-based creative activity, or is it something more?

During the early 19th century Horace Mann described drawing as “an essential industrial skill” and as a “moral force”. John Gadsby Chapman declared, “Anyone that can learn to write can learn to draw”. In his introduction to Graphics, his 1834 textbook for a high school course of drawing and penmanship, Rembrandt Peale compared drawing to handwriting, a basic skill required by an educated citizenry.

Is it appropriate today to continue discussions about issues of style?

How does drawing affect creative practice? What are the most effective ways to promote drawing to improve visual literacy, design, and spatial reasoning?

Dr. Robert Root Bernstein argues that scientists who make art make better science. Pre-college education has abandoned cursive penmanship while a few stalwarts insist that not only is it an essential skill, but also a powerful aide-de-memoire.

During the last few decades programs have emerged, devoted to the mastery of observational drawing; not exclusively to train artists but to provide anyone who values learning with a visual language to decode the forms of nature and design.

What are new priorities in drawing instruction? In the immediate future, what roles are to be played by traditional academic drawing, avant-garde practice; experiment, play and provocation, performance, revisions to foundations curricula, writing in longhand, drawing on computer tablets, animation design, easel painting and artists’ books? How will higher education make the study of drawing more relevant to the post-millennial students? How might its new approaches validate drawing for K12?

Presenters will each identify their top priority for advancing the study of drawing.

LEARNING TO SEE ANEW: PRIORITIES IN DRAWING EDUCATION

PANEL DISCUSSION AT 2:00 PM, FEBRUARY 13, 2014 AT THE ART STUDENTS LEAGUE OF NEW YORK, PHYLLIS HARRIMAN MASON GALLERY, SECOND FLOOR 215 WEST 57TH STREET, NEW YORK NEW YORK 10019

MODERATED BY JAMES LANCEL MCELHINNEY

PARTICIPANTS

JEFFREY CARR, Dean of the School of Fine Arts, PAFA

BRIAN CURTIS, Director of the Studio MFA program, University of Miami

PETER KANIARIS, Professor of Art, Anderson University, South Carolina

SAMUEL MESSER, Associate Dean, Yale School of Art (Respondent)

JOHN RISE, Professor of Art, SCAD, Session Chair at FATE 2015

FLASH ROSENBERG, Cartoonist, Animator, Humorist, and Guggenheim Fellow for Live-Drawing, pioneering Artist in Residence for LIVE from the New York Public Library

PETER TRIPPI, Editor in Chief, FINE ART CONNOISSEUR magazine, President, Association of Historians of Nineteenth Century Art.

Interview with Helen and Frank Hyder on March 19, 2014: the complete conversation

PARTNERS IN ART: FRANK AND HELEN HYDER:

The complete interview conducted March 19, 2014

James Lancel McElhinney © 2014*

On March 19, 2014 I sat down with Frank and Helen Hyder to talk about the origins of Projects Gallery, moving from Philadelphia to Miami and the challenges of balancing a serious studio practice with the delivery end of the art business. We met in the library of the Art Students League of New York

James McElhinney: I am speaking with Frank and Helen Hyder on Wednesday the 19th of March 2014 in the library of the Art Students League of New York 215 West 57th Street.

So, welcome. We’ve been talking a lot already. So, I’m curious. I’m assembling information for maybe a book, maybe some articles, maybe some other things; and you are two people whom I have know longer than almost anyone else in the world. And, also you are two people who have sort of taken an unusual path which is Frank as an artist, who toiled for years in higher Ed and tried to balance a career as a painter against the demands of teaching in a small, gender-specific art school, and Helen, you were the personal secretary assistant to the present of Hunt Manufacturing. Is that correct?

Helen Hyder: Well, not to the president. I had other administrative duties but not to the president. But you got it close.

JM: You were in the executive suite of the administrative doers.

HH: Yes.

JM: And so the upshot is that you are working together. Frank as an artist, you’re in the studio every day. But you took a kind of a prescient move, which is that you opened a gallery. What inspired you to open a gallery?

HH: A couple things. My company was bought and I was invited to follow them to Ohio and I declined. And we had just renovated our building and were going to rent it out and we had talked about something retail; but in the backs of our minds was the idea that for years I had watched him get screwed over, for better use of the word, by dealers in terms of not being honest with artists. As we’d been talking about, taking in inventory selling it and not paying and then suddenly we don’t know where it is, and artists aren’t good at record keeping, so one doesn’t know who has what. So there was that sense of doing something that wasn’t so much based on greed and retail but more so presenting work honestly and ethically and paying the artists first before anything else. And that’s really what the premise was and I started it in August of 2004, put on a show of our friends and had no idea what the heck I was doing. And he said to me, “Where’s your press release?”, and I said “What the heck is a press release?” We put on our first show and sold some work and that’s how we got started. And I can say in the ten years we’ve been doing this that I have been able to follow that initial creed of paying the artist first before anything else.

JM: What year did you actually hang out your shingle?

HH: 2004

JM: And what month? Do you remember?

Frank Hyder and HH: August

FH: And so I knew something about how a commercial gallery worked and, having been affiliated with an education institution for a number of years, I knew something about how university galleries worked. And I knew something about how museums worked and then I had just come back from doing a senior Fulbright research, a year in South America, where I’d done a lot of interacting with museums that were working in community-based operations and things like that. So, we created a kind of a hybrid gallery that was not purely a commercial gallery. We reached out and established liaisons with arts-based institutions, the first one being Mural Arts of Philadelphia. We then reached out to Taller Puertorriqueno; we reached out to the Brandywine Press, which is the oldest black printing press in the United States. So by reaching out and creating a network and bringing them in and then discussing a kind of a show that we could put together and put on in our space, it created a dynamic. We existed in our space sometimes commercial, sometimes public; but it enabled us to really form-shift frequently and create venues and opportunities that brought an immense cross-section of groups through our door. We would also allow our space to be rented by corporations and businesses for special receptions that would bring new people in just to see what we had on the walls. And we even became the host for two years for a minority business entrepreneur that would come and set up little mini business fairs one night a month in the gallery to kind of create a dynamic and introduce the business model to people who pretty much had never had any exposure to it. So what we were trying to do was build a number of–if you imagine an aerial view of a lake you can see where a deer comes to the lake and other animals leave paths in the grass. Our idea what to see that as many different paths as possible would lead to that lake. Not with the goal of making a lot of money but basically creating a site where work that was not in the public domain, was not being seen as frequently, got the same level of respect. So, there were times when we put on mini seminars, and we had writers from the Philadelphia Inquirer, the architecture critic; we had a sociologist that wrote books; and we did a show that was based on the dynamics of urban renovation in concert with how artists change neighborhoods and then developers drive artists out of the neighborhood. So, anyway, over the ten years we built a press book of an immense amount of reactions to what we were doing and got a pretty good rep for doing it. We would let artists come in. We had a space we built in the basement. We would let artists come in and build an installation that could be up for months, and it would take weeks to put it together and we would let it stay. These were all models that exist, but they didn’t really exist on a commercial network. At the same time, we found the only way we could really fundamentally create enough money to survive was by going and doing art fairs. So within six months of our first business operation—

JM: How did you discover that? Not to interrupt you.

FH: Well, somebody suggested that since we had a real gallery, we could actually maybe go to an art fair. So we took a loss lead and we tried it. What I did was I went around and I got a number of artists and I invited them to be part of what we were doing; and they would all pay a small amount toward the collective whole cost, with a guarantee that they’d have an equal amount of space and equal promotion, and they’d get their money back as soon as we sold anything. So it was again a novel concept because it was very cooperative. We put together our first show, which was Art Miami, in 2004.

HH: 2005

FH: Yeah, 2005, January; and we realized instantly that we could generate enough money in these types of events to keep the gallery running for months at a time. So we followed up with others; and now at this point, we’ve done more than 60 different art fairs over the ten years of business. In as diverse places as London; Toronto; Caracas, Venezuela; Santa Fe, New Mexico; Miami; New York, etc. And, that has given us other things, which is exposure to a pretty good level of galleries. We’re not a top-tier gallery. We’re interacting with all of the upper level, second-tier galleries, good quality; we have many friends here in New York. And for me as an artist, the dynamic suddenly changed. I walk into a gallery and the dealer is happy to see me. And we earned our stripes or our respect on the field of that arena. And we learned—it was also like a mini seminar every time we would do an art fair. We’d have down time where we could learn from other dealers, how you deal with this situation.

JM: I can imagine everybody’s learning from each other because the scene is evolving all the time and changing so rapidly, and so you can’t just come up with your branded paradigm and it may not work. It may work one year but not the next

FH: And it’s in the tradition of the great bazaars, as opposed to a great market, because the openness of the art fairs, the clustering of space, and the cross-semination of ideas. Where you’d see something out of the corner of your eye and you’d say, “I you think I know how to do that”, and you try to incorporate it into your next fair. And so it led to a kind of building of a stable of artists that we’d picked up so we had artists from Cuba, artists from Canada, artists from Venezuela, all under one umbrella.

JM: How did they come to you? Did they find you or did you find them?

FH: Generally we would see them at an art fair or she would get a response from them. For example, we did the a fair in Chicago one year. After we had set up, I went on a vision quest of sorts, a sort of dream search; and I went to a couple of the fairs. And I went to one of the fairs and I saw one artist. I came back with his name on a piece of paper, and I said, “This is the best young artist I’ve seen in 150 spaces.” His name was Caleb Weintraub. We contacted Caleb and said, “How’d you like to do a show?” Well, he was interested, came to Philadelphia, we set him up, we did a show, we got him a bunch of talks and things. But the show we had previewed in our gallery in Philadelphia and then left our gallery and went to Jack the Pelican in Brooklyn afterwards. The result of that, we were actually creating venues and helping artists create images. We co-curated shows where we put Latin American artists together with one another. We did things with Mural Arts. We then were in Mexico City at a mural conference, where I met the daughter of Diego Rivera. After I met her, I spoke to the people at Mural Arts in Philadelphia, I said, “Look what we need to do is bring this woman to Philadelphia, to the art museum, for a purpose.” They arranged it; they brought her. Meanwhile we staged in our gallery a show of Latin American art. She then came from the museum to the gallery and gave a talk and we filled the gallery with people. Those were the kinds of think-fest, lets-make-it-happen ideas that we could get from the diversity of interactions we were having. We were not traveling normal channels. And so, we talked before about this notion of the “gallery system”.

JM: It doesn’t really exist, does it?

FH: But the idea of that you sign with a gallery and that gallery sort of takes care of you and shows your work and represents you, and there’s a sort of commitment.

JM: Like the Castelli model, which was and is very rare. It was rare when he was doing it, and it’s still rare.

FH: But that model, I saw a way to do it differently. So what we did, we didn’t know how it should be done, but it was like kind of on instinct and then as we did it we adjusted ourselves. So her organizational skill and her managerial skill created an excellent cup to hold the fulcrum of ideas that we were throwing in and seeing what we could get. And essentially what began to develop were new forms. And I, for the first ten years, have only had three shows in the gallery.

JM: There are two little housekeeping questions I’ve got. One is, when you decided to open this gallery, what you’re describing to me sounds an awful lot like something that would be a good candidate for a new 501C3. Did you think about making it a not-for-profit and going after donations, or what made you decide then run it as a business?

FH: Well, the problem with this idea of becoming a not-for-profit is that that’s a language unto itself: writing for grants and appealing to the grant cycle—

JM: Meaning wealthy people write you checks?

FH: Yeah but there’s a kind of popularity in what ideas are getting aired, and what we found was something that when you and I went to art school didn’t exist in art school – this notion of “Mixed Media”. Our idea of mixed media was charcoal and white caulk.

JM: You mean like what Bob Rauschenberg and people like that were doing?

FH: They were the beginnings of something that Picasso began at the turn of century with cubism. But what was beginning to emerge was artists that were working materials that were non-traditional and at times mixing them with very traditional mediums and creating forms and methods of communication, media, whatever you want to call them, that really hadn’t existed before. So that became our focus. Every artist we worked with became a master of his or her material. We looked at them. They had to be working in a highly proficient manner with a material in a very personal way. So we weren’t looking for a classical painter. We weren’t looking for a painter who had classical skills but maybe painting with wax or painting with cut paper, something different. So we found an artist who made castings of negative shapes of teddy bears in Toronto. These were brilliant things that looked soft and fluffy but were made of concrete. We found an artist who carved into telephone books and made detailed portraits of popular figures—I mean it’s in the manner of Andy Warhol but it’s also very unique in the way it’s made. We found artists who had approaches to making imagery and making subject matter that sometimes incorporated found objects, cut up credit cards, all sorts of things. And we created an umbrella under which all of those things could be housed and seen.

JM: So you decided to go for the enterprise model. That made more sense to you.

HH: Grant writing doesn’t sound like a lot of fun to me.

JM: Well, its not just grant writing. It’s begging wealthy people. People I know who run foundations talk about the caring and feeding of the very rich, and it can be very unpleasant work. So this idea of enterprise is interesting; I hear this more and more. When I interviewed a pair of Chelsea dealers maybe six or seven years ago, I asked them what kind of artists they would like to show and they said they’d like to show artists who can do what they do, or at least get it. They were willing to put up with a couple of prima-donnas, but they actually liked working with artist who actually understood the business of art or how to be a business person or how to be organized or who could, if they dropped dead, could maybe run the gallery for them. I think that if you look at a lot of successful artists, a lot of them are very organized. I did a small project with the Rauschenberg Foundation, and I was blown away. Bob Rauschenberg from his earliest life would take photographs and clippings, and it was part of his artistic practice to, to sort of scavenge images. But he actually put all the records in binders, all of them in loose-leaf binders, all of them in files, so that when the archivists had to come along and organize them all it was pretty much there. He was a very organized guy. According to the people, I never knew Bob Rauschenberg, but according to everybody I interviewed, they said that Albers hated him, thought he had no talent; but he revered Albers because Albers taught him the importance of being organized. So I’m just wondering, one hears a lot of people complaining about how the art world is changing and it’s not like the art world they knew, the galleries are having trouble. But we also hear of a lot more artists going pro. The spectacular example of that being the Damien Hirst auction. The artist sort of running their own business: Jeff Koons, Mark Kostabi (I guess he’s still around), Warhol too.

HH: But then most artists couldn’t do that. It’s like the government wants everybody to run their own IRA. Most Americans wouldn’t have enough financial knowledge to do that, and most artists don’t know that either. So that’s one of the ways the galleries and the art centers and all those people help them, because most artist just want to be in their studio making work.

FH: Five hundred years ago every artist had to be some kind of a small businessman, had to understand something. And really probably the first kind of merchant artist would be Rubens, who really created a network of trainees, experts, and a marketplace approach, and a real sense of a global commitment.

JM: He adopted the Venetian model.

FH: But he traveled, he painted, he sold, he advocated something that the Flemish masters had developed which was oil painting and canvas, which were transportable easily, not painting on walls. And in the 19th century, many don’t even realize that Paul Gauguin was a stockbroker for while in his life, and a bookkeeper, and a mariner, and he had these various and sundry experiences. He was tarpaulin salesman in Denmark. He had business behind him. And so, when he finally made his commitment to just being a full-time artist, he had savvy about how business was done and how it could be conducted. And he found himself, while in Tahiti, he was an anti-colonialist; and, in fact, it is one of the reasons it is believed he died because he’d been sentenced to go to jail for speaking against the French in favor of the natives in Tahiti. And he overdosed on morphine. Jeff Koons did time in the business world. Jeff and I went to school at the same time. So I think that model, maybe not every artist can do it, and I don’t think it’s something you can teach in art school. But it is something that is very much doable, and that is that you can have some control in your own destiny. So I, now, ten years after we started a gallery, I have relationships with galleries who show and sell my work. I have art fair experience, sometimes showing with them and sometimes just showing with our own enterprise, and I have more experience than I’ve ever had before, and I have power.

JM: So you would suggest to other artists that they should explore ways to do more for themselves.

FH: Totally, and I think that they should know how the market works. “When your work is ready,” as Joanne Mattera said to me “when the work appears and the edges haven’t been trimmed and its rough and ragged, that’s like going out to a fine evening dinner and your underwear is showing.” You have to get real about all those things, and those are details, but they’re giant details that change the game. The other thing that I’ve learned is my work is market tested. I know it’s going to work at that price in every market because we floated it. We started at a price, and it achieves its own level. Then something has to happen to push it to the next level.

JM: How do you feel about studio purists accusing you of being a shameless self-promoter?

FH: Well, I think that that’s fine. But I think that if you want to be a Trappist monk or if you want to take a vow of silence and if you want to read the bible and pray daily, I have nothing against you. But at the same time, somebody who’s out in the field doing the work that you propose to support and believe in, don’t judge them either. There is the famous story of Saint Francis of Assisi and his accomplice riding up to the wall of a medieval town and his associate says, “What are we going to do when we get there?” and he says, “Well I’m going to talk to them about the goodness of God and God’s mercy and the love and all these things.” The accomplice says, “Boy, I can’t wait.” So they go into the town. The first thing they do is to greet the mayor. He stops and gets off his horse. He pats the mayor on the back says, “It’s a beautiful town you have here.” He goes down the road a little further and sees a man’s cart has a broken wheel. He goes over and helps lift the cart so they man can get the wheel back on. He stops and talks to a lady who’s doing some wash on the street. Next thing you know they’re on the other side of town and his assistant says, “When are you going to give that talk?” Saint Francis says, “I just lived it.” If you want to stand on a podium or in a sermon and make pronouncements about the importance of your purity and piety, that’s one thing; and that’s your right to do it. But at the same time, leave alone those people who are out there in the field trying to live that life and dealing with compromise that real life offers. And hopefully both methods are valid.

I had a conversation with an artist in Baltimore about a month and a half ago, and we were looking at one of his pieces on the wall. I said, “How much does this piece sell for?” and he gave me a price. I said it was a realistic price. He said he wouldn’t take anything less than that. I said, “Well, that same sized piece I get about the same amount of money for it, but I have to sell ten or twenty of those in a year to survive.” So I said, “I know I can sell them and you can afford not to sell it, so there’s a difference there. I wish I had that luxury of the support of an institution.”

JM: I interviewed, among other people, I one famous and successful dealer who still runs a gallery in Soho. I asked him,

“What are you going to do about an artist who you sold work for last year for $50,000, and now no one is going to buy it at that price point?”

He said,

“We lowered the prices. We have to meet the market where it is. It’s just like stocks, real estate, everything else. You can’t invent a price and say ‘This is the price.’ I know a lot of artists believe: Okay, I get out of school, I have my thesis show, and then I paint a couple of practice gallery shows, and then I have a gallery show, and I set my prices with the dealer, and every year we try to build the market.” (Helen Hyder is smiling and shaking her head.) “The expectation is just going to keep going up.”

Helen Hyder: Real estate doesn’t keep just going up. You know how many times I’m working with a new artist and they give me their work and they tell me their prices—if they can tell me their prices, many of them have no clue, and I ask them,

“What are you basing your price on?”

A typical response might be, “Well…it took me a really long time to make it.”

My response is, “That’s your decision. You can’t base it on a by-hour rate.”

James McElhinney: Well this is one of the things about artistic quality that a lot of people have said, the age of industry, collective bargaining, and the whole idea of the hourly wage has made some kind of abstract equation between the value of something and the amount of time it takes to make it. So you could spend a lifetime making something completely worthless or you could make something magical in a minute. So it’s actually what you’re dealing is what you’re dealing.

Frank Hyder: And I have a warehouse filled with work that I’ve made over 35 years that is powerful, perfectly good, high quality work that didn’t make the market. I did sell lots of work during that time, but there is that storage.

JM: That’s what they call “research”.

FH: Right. And so, you can’t look at making a single work of art if you are a real artist because you have to think in terms of a seminal body of work or a complete life of work. When we started doing art fairs, there are galleries that do one or two fairs a year; but then there are galleries that do many fairs in a year

HH: 18, 20,24

FH: Yeah, we know dealers from Spain and Mexico and from other places, London, that do 18 fairs a year. What they do now, instead of looking at the numbers from a given fair and say, “Oh we’re losing money here.” What they do is put it all into one box for the whole year, and they dollar-cost average the whole year out, and they look at how the business is. Like I said earlier, we did a fair this year where we lost almost everything we invested. We’ve had other fairs where we did that as well, but we came from that fair really quite behind. But while we were there, we met an artist who we had never worked with before. We started a dialogue, and the next time we did a fair, two months later, we showed this artist. We sold enough of this artist’s work at the next fair to cover the complete loss. So when we look at that we say neither fair was a failure. They were both a success. Because sometimes you walk away from one fair with a new client or a new artist, or you walk away with a possible sale that doesn’t happen for two years

JM: Well you used the term a while back; you spoke about taking a loss leader. This is a basic concept that you offer a product at below value to get people to come to you, and a lot of dealers in this town do this too. They’ll actually get the artist’s inventory in the gallery and they’ll give a piece to a museum if the museum will take it, or they’ll give a piece to prominent collector–

HH: Well that’s building a resume, yeah sure.

JM: Building a resume but also marketing, because if you give a piece to a museum, they hang it on a wall, people see it. You give the piece to a top collector. They’re having cocktails. People see it. Nobody’s going to be rude enough to ask,

“How much did you pay for it?”

FH: We live in a new time; everything’s different. When you and I first started making paintings, you made a painting then you made a slide, you had to get it developed, you had to send it to somebody.

JM: Technology.

FH: So technology has changed. But also, other technologies have changed. For example, when we opened, it was one of my feelings that we had to have a state-of-the-art website. It had to be absolutely the tool. And we have a counter on our website that can show us where people that are visiting our website are coming from. So we’re sitting the gallery in Miami or Philadelphia, we can see on the website that we have somebody in Toronto, Canada looking at certain pages on the website and how long they’re doing that. When we’re about to go to a new site for a fair, we will have an increase of hits on the fair, and we’ll see what they’re looking at and that can aid us in picking out the work to bring to the fair so we’re prepared for what’s going to happen. These technologies, not every gallery takes advantage of these, but the ones that are succeeding and surviving are employing every one of these strategies that you can find. At the same time, it’s not necessarily about making money, because there are a lot of galleries making lots more money all around us. Our strategy is that we’re surviving and we’re showing the things we care about. That matters, too. Just making money is not what it’s about. The commodity issue—that’s something that, after 35-40 years in the business, gets a little tiresome.

JM: If success has a dollar value, as they say in Hollywood: there’ll always be a smarter agent, there’ll always be a bigger part, and there’ll always be a prettier girl. And you have so many people in the world who have so much money, it’s gotta be also about doing what you want to do.

FH: And there are new forms, too. For example, we did a fair and this man came up and talked to me at length and it turns out he’s the CEO of a cruise line who has a particular interest in art. He has several ships, and on these ships he has a number of works by Picasso, Miro, Mendive, Wilfredo Lam. The collection is immense, and it’s spread across luxury cruise lines. As he said to me,

“The top two percent of the nation are riding on my ships. I’m going to give them a visual diet that is equivalent to their status and their economics.”

So he approached me about making some paintings in my mixed media that would be weatherproof, and we started with a small block of commissioned paintings. I just finished my 32nd commissioned painting for this line. He also built two ships that incorporated a 1,000 square foot art studio on the ship, and he puts together artists residencies. So he puts an artist on the ship for a month or for two weeks, and he gives them a working room and supplies. He allows people to come into the space and see art. He just took what they do with the cooking classes and all these different models and applied them to art. I’ve been told that people like Dale Chihuly have done these things. The playing field is different. We are leaving on the fourth of April for Tahiti, where we will get on a ship in Papeete, and we will sail from Tahiti to Chile.

HH: Peru. Callao, Lima.

FH: Peru. We’re stopping in Easter Island, Bora Bora, many of these other sights. And I will be working as the artist for that month on the ship, making my work, interacting with people, dining with guests on the ship, and talking about the other art that’s on the ship, which includes Picasso, Miro, etc.

JM: There was, a few years ago, maybe 5-6 years ago or more, someone was running an art fair on a boat.

FH: Oh they would be the Lesters. We know them very well. We’ve done that fair five times.

JM: Is it still going?

FH: It still exists. The ship is mostly docked in Miami. They do occasional ventures. The quality of the ship is extraordinary, and the experience is interesting.

JM: They were going to places like Charleston, Savannah.

HH: Now they just stay in Miami.

FH: We know them very well. We’re aware of a whole bunch of things in the art world—

JM: What’s the name of the ship?

HH: The SeaFair.

FH: SeaFair is the name of the ship, and their organization is called International Fine Art Expo. They founded…they were the founders initially of Art Miami back when there was only Chicago and Art Miami, the two art fairs in the United States. They founded Art Palm Beach. Here in New York, there are a couple of guys we met a few years ago in Miami and they started doing a hotel fair, and they’re called the Select Fair. They came to me, because they knew my work, at some venue they had seen me, and they came to my studio to talk to me to try to convince me to do something in their fair. When they saw some work I was making, they offered me the opportunity to install these transparent pieces in the windows in the glass stairwell in the space. So, I ended up creating a new piece of work that worked in that installation. I wouldn’t have made it had they not come to me. In the process of them coming to me, our interactions, I gave them a lot of observations that we had made from doing 50 fairs previously. They took that information and heeded many of our suggestions and now in May we’re going to do a fair with them here in New York. They’re doing their first booth fair. They’ve gravitated from hotel fairs and they’ll be doing tent fairs in Miami this year. They’re living off the art fair.

JM: So, in other words, what we were saying earlier, Helen and I were talking, I shared that I had conducted almost fifty interviews with some of the top dealers here in New York and a couple other towns like Chicago and LA and that it seemed to me that the reality of it was that there was no gallery system such as the schools wanted everyone to believe. The art schools were preparing students for a gallery system. There’s no system. There were a bunch of individuals who ran galleries with as much differences as retailers in any line of work.

FH: Let me clarify: there’s not an art gallery in the country that cares whether you went to school or not. The only thing they want to see is the work, and whether they think they can sell it, and whether their audience wants to see it.

JM: I interviewed Marian Goodman, Angela Westwater, Arne Glimcher and many others. I recall asking each of them,

“How many of your artists have MFAs?”

Most of them say they don’t know, and don’t care. Like you said, it’s about the work, not the degree. That only carries weight if you’re looking for a day job. It has almost nothing to do with why a dealer wants to represent an artist.

FH: What’s a requirement is the ability to create work that people want to buy. An art gallery doesn’t exist just to sell art. It’s a place where people who are interested in art come to look at it. It’s a place where artists come to look at it. It’s a place where writers come to look at it. It’s a place where clients come to look at it.

JM: Say, the reason why a writer needs to get a book published is so they can read it, so they can experience their own work. The reason why an artist benefits from exhibitions is like getting a baby’s out of the womb, or the wine out of the bottle and into someone’s belly. An artist takes the work away from the safety of the studio and hangs it naked on a strange wall. It is the first time one can actually see it one’s won work with honest eyes. Frank, I want to ask Helen a few things.

Helen, because for many years you were a long-suffering artist’s wife, watching Frank— who is always extremely enterprising and very industrious—watching him deal with a parade of rascals and thieves, along with a few nice people too. You worked in the business world, working in a completely different environment informed by a whole different set of standards. When you guys decided to form the gallery, what was your level of confidence in terms of choosing artists to represent, what was guiding you? To what extent were you relying on Frank?

HH: In the very beginning it was just I, relying on him totally. I came to discover by accident that I actually had an eye. I don’t know anything about art. I have no education in that area.

JM: Except that you’ve been living around it for thirty years.

HH: I’ve been living around him (Frank Hyder). You and I have been friends for a long time, I’d walk into your studio, or maybe Doug Wirls’s studio, all these other artist’s studios, and I’d say, “Oh, I like that. That’s interesting.” But I had no historical reference. I had no idea what I was looking at. I went through a period of time where I would put on these group shows of graduating students from all the universities in Philadelphia. I would go to every senior thesis show. I would go to many studios, and from that I would pull together a show based on “fresh”, fresh ideas. And they were pretty damn good shows, and I picked them by myself. It was then that I realized that I could actually see what they were trying to say and create a language. I still rely on him, but it’s kind of funny. We’ll walk into a show and I’ll pick the things I like, and I’ll bring him around and we pretty much pick the same thing. Maybe its because we’ve been together for 45 years, I don’t know; but I think it’s because there’s a synergy between us as well. There have been artists I’ve pulled and I want to work with this artist, and he’ll go, “No, I don’t think so.” And I’ll be persistent and he’ll finally acquiesce and I was right. So I think he’s learned to let me have an eye, because his level of what he wants to show may be a little higher than mine. He often says I have an eye for the Craft, but I think he’s learned to trust that I have an eye for what the industry wants as well.

JM: Well, I think that what you’ve both been saying is that Frank, as an artist, has an aesthetic agenda and a different sense of the nature or the character of the body of work he’s trying to produce. Whereas you, as someone who has interacted with artworks without a specific purpose in mind, now that there’s a purpose, that purpose has let you organize your ideas about it in a way that has shown you that you can make choices with confidence and actually be right a lot of the time.

HH: Well the other thing, Jim, in any gallery, with any of the dealers, you’re going to see the same thing. Out of a hundred artists, twenty percent of them support the operating function of the gallery by sales. The other eighty percent you just like, like to show their work. They may not financially support what you’re trying to do.

JM: But they help you to deliver an esthetic message. It’s like what you’re saying about the two shows. One of them was a bust in terms of sales but the other one was a huge critical success, so it all averaged out in the end.

HH: But there are galleries where if you don’t meet a (sales) quota, you are out the door.

JM: People will come into the gallery to have a look at particular artwork because it attracts them, and then they might leave with something else.

FH: That’s right, and art fairs have a particular character. The glitz, the things with bling are very attractive. People are drawn to those things. We’ve had a conversation with a dealer from London, from Quantum Gallery in London. He’s been in the business for 30 years, and I asked him for his observation in the way we do our shows. He said, “Well, it’s very clear that you understand that you have to create a visually interesting space, and you have to invite people in to see what’s right over there in that corner, and that reveals that you’re paying attention and you have experience in doing this.” And at the same time, what we know is that if you want to succeed, you show up every day and you tune, readjust, move, change, try different strategies, because every time you hang things on a wall, it’s a strategy to get people’s attention to look at the thing.

HH: You have five seconds.

FH: Yeah, you have to get someone’s attention right away. And you’re competing with an immense number of things. So if you happen to have artist who gets mentioned in an art article about a fair or a blog article about a fair or photography of their work appears, and we’ve had them show up on national news, national news in Canada, we’ve had them in the major papers, we’ve interviewed in Chicago and in Houston. And we’re a little gallery. We don’t have resources. We have a small agenda, but we have a program, and that’s the way a really good gallery that does shows at fairs looks at it: you have a program. You have a point of view you’re trying to present and you have a group of artists that you believe supports that point of view. Some of them are going to bring people in the door, some of them are going make you money, but they work synergistically off one another.

JM: So in other words, creating a gallery is a form of installation art.

FH: It is a form of installation art, absolutely. And the arrogance and the pomposity of some galleries is visible immediately from the way they install their work and their generosity and openness by the way other galleries install their work.

JM: I don’t need to ask you which side of the fence you guys fall on.

Frank Hyder: We got involved with an artist, a Cuban-based artist, who approached me about six years ago with a project he was doing and he wanted to create a group of inflatable sculptures. This is out of the galleries, but to take place during an art fair time.

James McElhinney: Literally pop-up art.

FH: So, I said from day one, “I want in.” So it revolved around commitment of each of us. We had to put our own money up to make these things. So we’ve got José Badia and Thomas Essen. We’ve got very established artists, all of us down there in the mud, driving stakes in the ground, running extension cords, turning these things on. So we had our 10 monumental pieces go up. It was a killer as a piece. The great thing about them is they fold up, and you can take them in a duffle bag and get on an airplane, which I actually did and I flew to South America. I set it up downtown on the streets in Caracas. I then went by plane into the Andes Mountains going village to village. I’d set it up in the town square. Everybody would come down around the thing and have their picture taken with the art. I’d talk to them about what I was doing, fold it up and move on to next place. I didn’t get paid. Nobody funded that.

JM: You should have had a video crew running around with you.

FH: But the idea was smashing. So when last year a show was curated here in New York City by the Maryland Institute of 162 years of its graduates, they took a small number of people to put together a show. I was included in the venue. And when they became aware that I had these monumental forms, up in Beacon they had three of these things. They were unique. The art students were mystified by them, and here I’ve been making these things and producing them in different sizes and dragging them around. I’m not making any money on them, but I’m doing it for the love of art. So I take the money that I get from selling another painting, and I put it into those.

JM: So, in the ten years since you’ve been operating a gallery, and obviously you’ve been nimble and adapted and grown and evolved as the scene has grown and evolved. In the ten years since opening your gallery, which you call Projects Gallery, was there a discussion about what to call it?

Helen Hyder: Yes. When we first opened, we actually called it our last name, Hyder Gallery.

JM: Why did you decide to not call it “Hyder Gallery”?

HH: Well, we did our first art fair; and the director of the art fair knew that I was green. She pulled me aside and she said, “Let me give you a piece of advice. If you don’t want to be seen as a vanity gallery just representing your husband, you either need to change the name of your gallery or that’s what you’re going to be perceived as.” I took her advice, I was mad at first. How dare she, but she was right. So we then went around figuring what the hell we were going to call it. Most dealers usually call it their name, and then we started doing these things with Mural Arts and Brandywine, and we said well we are doing these projects.

JM: Well, it was that time Jeffrey Deitch had Deitch Projects, and there were a lot of people. It was a word that was in the air a lot.

HH: Right. So that’s partly the reason why. There was a moment there where even though we’d been married for so long, I went back to using my maiden name because it became an issue with people. “Oh you’re representing your husband, so we get a special price.” And that was an obstacle I had to overcome. And then I got to the point where I got tired of being schizophrenic, and I just went back to using my married name. When people come into the booth or the gallery, and they look at his work, and I present his work at the level that I do, at some point they’ll say, “Are you related?” I’ll say yes, he’s my husband, and it’s not an issue. And they’ll understand that he’s just one of many artists. Yes, it is my husband; it’s not that he gets special attention. Everybody gets treated the same. When he’s in the booth with me at the art fair, they talk to him as though he’s the dealer, and then they read his nametag and they say, “Oh! You’re the artist.” and it’s generally not a problem.

JM: Well, there’s something to be said for an artist wanting a gallery to get it right, too. Like, you can say you did this for 30 years before we decided to do this. Like I got tired of having to rely on people I couldn’t work with, or I couldn’t work with in a completely transparent way, and we just want to get it right.

HH: Well, an awful lot of artists can’t talk about their own work. They can talk about other people’s work. Like, he can sell other people’s work much better than he can sell his own.

JM: Well, that puts you immediately at a disadvantage because at the end of the day you’re asking for money. It’s a lot easier to advocate for someone, and say wow this person is really great and you want to buy their work. And hopefully the buyer will get the idea that if you’re advocating this person, this person is really great. You must also be really great and they’ll want to buy your work, too.

So, in the ten years since you’ve been opened for business and doing art fairs, well, the first year how many art fairs were you doing?

HH: The first year we did—

FH: Two. We did Art Miami and then the one in Santa Fe.

HH: And then we did the one in December.

JM: So how many are you doing now? A year?

HH: We average about six shows per year. It varies. It depends. We’ve done as many as two at one time, which I refuse to do anymore.

FH: We’ve done five this year so far.

HH: But simultaneously?

FH: No, we’ve done five this year so far. And we’re about to do one more in May.

JM: That makes six in six months! So how do you physically do it? Have you got a half-container that moves around, those pods?

HH: NO. We’re a mom and pop operation, that’s what we do. Generally we do a fair along the east coast, generally, where we don’t have to ship it because shipping is extremely expensive. You have to understand, the booth fee is generally about for a small booth $15-20,000. That’s just to get in the door.

JM: That would be for how many days?

HH: Four days.

JM: Including set-up?

HH: No, and some days you don’t have a day on the other end. You close at 6 and you’re out of there by midnight. So you’re looking at $15-20,000 just to get in the door. And if it’s out of town, you’re looking at hotels, transportation, shipping, all that stuff. It can get pretty expensive.

JM: You have to entertain clients.

HH: Oh that’s fun. We could do that.

FH: You have a big expense; but for example, when we started, we did one fair that was our big event and maybe we tried another one.

HH: And we lost our shirt.

FH: And we lost money in the second one. But now we’re doing 5 or 6 ourselves, and I do with other galleries as many as 15 different fairs in the year. So about the venues…going back to this notion of how the art world is in a process of decentralization, echoing the reestablishing of economic centers—all these things are determining factors. You go where the clients are, and that’s how galleries are surviving. So on the books, the money you make in this town, or at the fairs keeps the gallery functioning some place else.

HH: Well, there’s another issue we haven’t talked about. When we first started doing the gallery, we went the traditional route of doing advertising; and we put ads in Art In America and ARTNews and all the major publications, $3,500 a month. You had no idea who was looking at you. They may have a circulation number, but you don’t know who is looking at YOU. No feedback, no sales. And so when we started doing the fairs, we said this is advertising, this is how we reach the two to five to fifteen thousand people who are going to see us this weekend. We know what they’re looking at, and we know what they’re interested in. So we can now adjust what we are doing. So when you look at the magazines now and you see that their advertisers are fewer and fewer, and they are always the same players over and over again, there’s a reason for that. It’s because people who used to spend money on magazine ads are putting that money into fairs.

JM: Well it’s partly, too, because of the tablet readers and the Internet and the print journalism is a dying—

FH: Like I said, we’re going to do this trip thing, we’re going to have the iPad there with us, with the gallery’s entire agenda in digital form. We’re going to reach out. They’ll be able to visit the website. Hopefully we’ll have small examples of other artists. We may in fact do business. So in a sense it’s a venture to create a different art fair, a little bit less competitive. We don’t have as many other galleries competing with us, but hopefully we’re going to make new clients.

JM: So what are the big trends that you’ve seen over the last ten years? We spoke about a few before we turned the recorder on, the idea that in a lot of the schools and colleges and universities studio programs are starting to fall by the wayside. Also the perception that galleries, specifically the physical walk-in brick and mortar galleries found in clusters like Chelsea, for instance, are suffering.

HH: There are many galleries that are not brick and mortar anymore. They exist purely on the Internet.

JM: Here’s one of my questions: I understood that at one point for a gallery to be considered for an art fair, they had to maintain a brick and mortar presence.

FH: That’s no longer though. In theory it’s true, but it’s no longer true. The other thing is you used to have to have an agenda, a program that you produced that demonstrated that you were doing at least six exhibitions a year that were real exhibitions. Today people create phony agendas and put them on the Internet and pretend they exist.

JM: Online exhibitions?

HH: The other thing is when we apply to some fairs they used to want to know your exhibition schedule. Now they want to know what art fairs you’ve done. There’s a hierarchy within the art fairs.

FH: The dynamics continue to change. Artistically, ten years ago everywhere you went you were seeing these gigantic digital photographs, manipulated in the computer, Photo-shopped. You’d see them hanging up everywhere. There was a period of time where you were seeing resin, resin, resin, resin, resin. Now resin is disappearing a little bit. Now it’s LEDs, new format lighting. Mechanical things are trending in.

JM: Anybody working on plasma screen display.

HH: Up-cycling is a big thing right now.

FH: A big part of what’s going on is that there really is this shift of things. The best place to see it all in one day is to go to an art fair, because you can walk stall to stall and you can see what I saw the first time in Chicago when I went to art Chicago in 1986. It was like Marlboro no longer had a fancy building. They just had a box right alongside the Fischbach Gallery or some other gallery. And suddenly the playing field was equal and the work had to stand on its own.

JM: Very interesting point. So without the theatrical installation art of the private parlor of the refined gentleman or the snob appeal of an upscale gallery with a haughty hottie intern at the desk who ignores you; so without all of that, everybody is just stuck in a box like everyone else, and you’re saying it calls more attention to that art.

FH: It levels the playing field. And the other thing is that in spite of all the manipulation and all the prejudice that people believe, when people go to art fairs, they really are pretty open-minded. And they look at everything or don’t look at it some times, and you can’t control that. They just look. They paid their money to get in the front door, and they’re going to look and enjoy it and they’re going to talk. It forces art dealers to have conversations with the people.

JM: That’s very new because I remember when we were in school and getting out of school and starting to show. The dealer was very often in this office in the back room and you were dealing with some counter-help, some floor sales-person, and only once you got past the interference of the public contact people would you be invited back to sit and talk to—

HH: Well, that’s one of the secrets we’ve learned. We can smell you a mile away. We really don’t want to talk to you.

JM: Well, it used to be that if you walked into a gallery looking like a artist—that’s why I always wore neck ties, is because people would not know that I was an artist.

HH: Yeah, but you would say some word that gave you away.

JM: But that’s changed, you’re saying.

FH: Absolutely. The whole nature of this conversation has revolved around how the field is changing. We’re sitting here in 57th Street in one of the most illustrious gallery streets in the world, and at the same time countless little enterprises are out there. People are trying to conceptualize new ways of presenting the work at the highest quality. We saw a fair this January that was staged in a circular tent near the bay of Biscayne, and the quality of the work was museum quality. But they were showing contemporary paintings with old sculpture and with fossils—all of it was top shelf, but the venue was so unique and the exposition was so extraordinary. We walked out and we felt like we had gone to a great museum.

JM: Well, I guess this is another question, because you, Frank, among a lot of the artists I know, were certainly one of the first to stop just putting a canvas on the easel and painting it. You were doing the woodcuts and painting the woodcuts. You were playing around with screen forms. You were doing ceramic murals. I remember walking into your studio on 2nd Street in Philadelphia and having tiles all over the floor and this kiln that was in some kind of jerry-rigged arrangement where you had to fire these things. But now I attend a lot of exhibitions here or I go to the museums where I am seeing more shows like the Rosemary Trockel exhibition at the New Museum last year. She had an Audubon print next to one of her paintings, next to a piece of pottery she’s done, next to an installation, next to a book by Humboldt. William Kentridge’s marvelous show at MoMA is a great example of many different genres being manipulated by one artist. This goes back to what you were saying earlier about how an artist’s work is not about just the individual piece. It’s about the body of work. We are seeing this more and more in artists like the Barbara Bloom, who recently organized a show at the Jewish Museum by drawing on the museum’s permanent collections. Artists today have to be polymaths, doing all sorts of different things. We would have accused them of being unfocused, “all over the place” back when we were in school. Artists today work across disciplines. They work in books at the same time they might be working 3D, or video. They make paintings and do performances, and do anything else they please. So how do you deal with an artist like that if you’re trying to intersect with a market?

FH: Well, let me just say that traditional galleries are still doing what they always did, which is attempting to pigeonhole an artist, to take the low hanging fruit, to take the stuff that’s easiest to sell and run with that. For me, the salvation has been that we’ve had our own gallery and I’ve been able to generate my own platforms. So that, as you generously pointed out, my impulse, which is historic now, goes back 40 years ago I couldn’t stay in the canvas we were taught in, I was working in other venues and crossing borders. When I was teaching that became a valuable skill that other schools recognized I could basically walk into a print shop or ceramic studio, a painting studio or a sculpture studio and actually function. And so I became the mixed-media specialist that was the guy that was brought in to liberate the program. But still the tradition galleries still want to go for the low hanging fruit. That hasn’t changed yet.

JM: When I walk in, there’s a room with one idea, all the paintings are the same

FH: And I don’t argue with those people. If they want to pick from my bush, that one fruit, that’s fine. But I don’t depend on them; I’m free to make it another way.

JM: With other artists, I mean for instance, I know some artists, let’s say another painter out of Philadelphia who is a little more traditional, who shows his oil paintings with one gallery, shows the drawings and watercolors in another. Some artists might show prints at one gallery if their primary dealer is only interested in painting. This was unheard of twenty years ago. Do you deal with any artists you’re only dealing with part of their productions?

FH: That may or may not happen because you’re going to be limited by the gallery who represents them. There is still a pecking order. If a gallery’s got a NY venue, it’s got more power than a gallery that has a Philadelphia venue. If a gallery is European based, it’s got more power than just a New York base. Those are old rules that are hard to shake. We’ll take the work on any terms that we can, but we also do not edit our artists. We let them come in and put this show together. We’ll lend our insight, “Maybe if you didn’t have this piece here, the whole wall would look better. Let’s try it and see where it goes.” Whereas, a lot of other galleries you don’t have that input at all.

HH: But, we have other ends of the spectrum. We’ll have an artist who is having a solo show drop off the work and leave and say, “You hang it.”

JM: That’s the way they want to do it.