TRACKING ELIZA. A DETECTIVE STORY. James Lancel McElhinney (c) 2020

Kathie Manthorne on the esplanade along the left bank of the Loing River, bordered by fragments of medieval defensive fortifications. September 16, 2019.

This story was published several months ago in serial form. Greeting each day now with artworks and travelogue, I share it here again, updated here with new information and images. Enjoy!

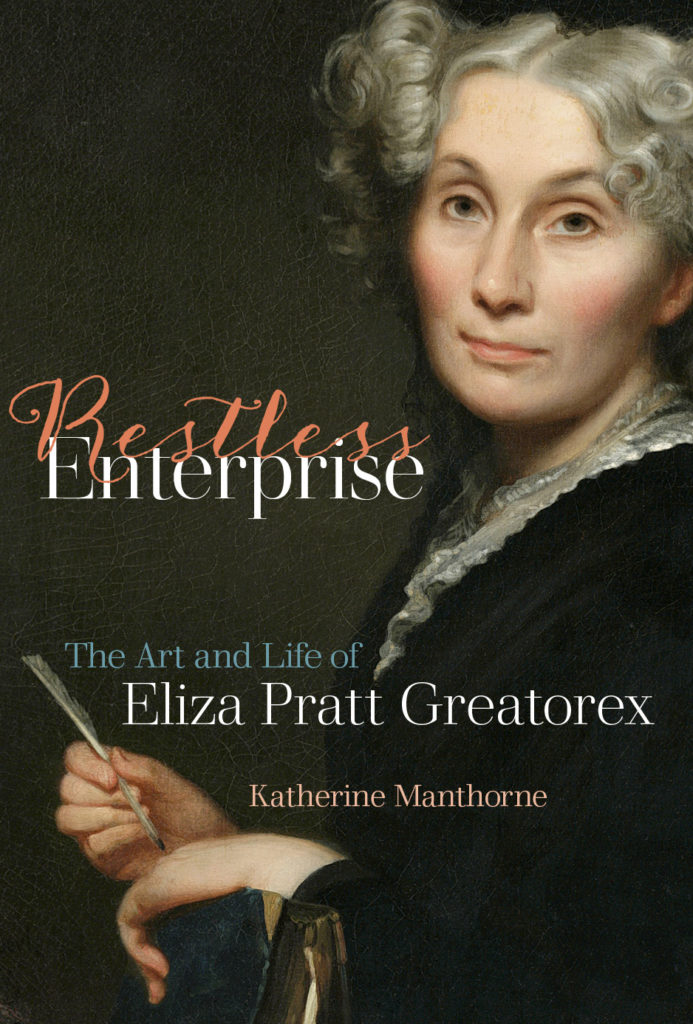

Eliza Pratt Greatorex (1819-1897) was a most remarkable individual, celebrated during her lifetime as “the first artist of her sex”. Shortly after her death in Paris, a Midwestern paper in a city where she never lived named her among the greatest women in American history. The story was published in syndication around the country. More than a century after her passing she is all but forgotten. That is about to change.

Eliza Pratt Greatorex (1819-1897) by Thomas Boyle. 1869

Collection National Academy of Design, New York.

(Reproduced under fair use, etc.)

Born into a large family, the daughter of a Methodist circuit preacher in Donegal, Eliza Pratt demonstrated a talent for drawing at an early age. During the great famine, her brother Adam emigrated to New York State, opening a dry-goods store in the town of Leroy, known today at the birthplace of Jell-O. Eliza followed, traveling in steerage from Liverpool, arriving in Manhattan, where she was welcomed by the city’s Irish elites. She later met and married a popular composer of church music; Henry Greatorex, son of the organist at Westminster Abbey.

While on tour in Charleston, South Carolina Henry succumbed to Yellow Fever, leaving Eliza with four young children to raise as a single mother. Drawing support from her brother and sister in America, Greatorex traveled to France in pursuit of formal training as an artist. Upon her return, she began exhibiting her work to some acclaim, becoming the second woman inducted into the National Academy of Design. As her children exhibited both musical and artistic talent, when they reached adulthood she brought them into her enterprise, and on travels to Europe and the American West. All the while Eliza developed close relationships with leading feminists. Among her friends were women like Susan B. Anthony, Mary Louise Booth, Grace Greenwood and Helen Hunt Jackson. Later in life, her health began to fail. She and her two daughters left New York, moving to the walled medieval town of Moret-sur-Loing, where all three ended their days. Eliza passed away during a sojourn in Paris in 1897. Records show Eliza’s coffin being collected from an apartment near Luxembourg Garden, then delivered to Gare de Lyon. She was buried in the Cimitiere Municipal de Moret-sur-Loing. Eliza’s sepulchre is inscribed with a verse; 1:John 1:5,

“GOD IS LIGHT AND IN HIM IS NO DARKNESS AT ALL”

Two years later her friend, noted Impressionist painter Alfred Sisley was buried in the plot beside her. Eleanor was interred next to her mother in 1908. Surviving daughter Kathleen Honora marked the graves with two stone slabs, memorializing three generations of her family. Kathleen passed away in 1942 and was buried on the other side of Eliza. Kathleen’s gravestone bears no inscription, but the three modest monuments merge into one. Inseparable in life, the Greatorex women remain united in eternity.

A tree and boulder marking grave of Alfred Sisley, Cimitiere Municipal de Moret-sur-Loing, Ile de France. Just beside it is the grave of Eliza Pratt Greatorex, flanked by those of her daughters Eleanore Elizabeth (left) and Kathleen Honora (right). Pebbles appear to be resting on Kathleen’s grave-stone, the only one of the three. Taking note of this and the year of her death (1942), one wonders if she had been brave as well as talented. (Photograph courtesy of Hans Christian Bohlmann).

Kathie Manthorne began researching Greatorex decades ago, picking up the thread between other books and projects. The process was vexing in part because Eliza left no paper trail in her wake. No collection of papers or letters, fewer documents of other kinds, and a handful of photographs. Her life had to be reconstructed by consulting public records; chiefly newspaper articles reporting on her comings and goings. Kathie and I have retraced Eliza’s peripatetic existence from Manorhamilton, County Leitrim, where she was born—to Pettigoe, County Donegal, where she was raised. We identified her various domiciles in Manhattan, Hoboken, Jersey City, Bay Ridge, Cornwall-on-Hudson, Leroy New York, and Cragsmoor artists’ colony in the Shawangunks of Ulster County. Following her restless path to Milwaukee, Denver, Manitou Springs and Fairplay, Colorado, we found traces of Eliza and her daughters in in Oberammergau and Munich. Apart from Tangier, only one place remained—her final residence at Moret-sur-Loing.

Landscpae Near Cragsmoor. Samuel Dorksy Museum of Art, New York State University at New Paltz. (Reproduced under fair use, etc.)

Last year Kathie completed the first biography of Greatorex, using her life as a kind of prism illuminating a new vision of American art-women in an age of promise. University of California will publish the book later this year. Pompidou Center and the Musee d’Orsay organized Faire/Oeuvre, a conference focused on artistic training for women in nineteenth century Paris. Kathie was invited to deliver a paper on Greatorex and her daughters. It was decided that we would arrive a few days in advance of the symposium. Landing at CDG Roissy, we were met by Michaal, who drove us to Moret. Beyond Melun we entered Fontainebleau Forest—the vast tract preserved today as a national park. I was struck by the condition of the understory—a tangle of brambles and ferns that reminded me in a way of the loving neglect I had observed in German woods, even in official parks like Berlin’s Tiergarten. We passed a plump, forty-something woman in yoga-pants setting up a lawn-chair, parasol and cooler by the side of the road. I asked Michaal if she were a vendor, or just a person who likes to sit on the shoulder of the road. She was a sex worker, he explained. Men pull over, she gets in the car, does her business and her clients drive away. It’s a racket, he said. She’s paying off the cops, who slap her clients with huge fines. I told him the story about going to a pub in Ramelton with my Donegal cousins. Parking a quarter mile away, we walked to the town center. At closing time, we all stumbled out of the pub into a blinding flood of light, provided by the collective headlamps and spotlights of Garda vehicles. I turned to my cousin and said, So that’s why we parked where we did.

Driving past Fontainebleau through another stretch of the forest to Veneux-les-Sablons, after ninety minutes on the road we arrived at Hotel de Cheval-Noir in Moret, a charming nineteenth century auberge on a corner of the Place de Samois, across the street from a monument honoring the town’s most famous resident—impressionist painter Alfred Sisley. The hotel is run by a married couple whom we later discovered are avid aeronauts who met through ballooning. Gilles de Crick was a successful chef who grew weary of the frantic world of culinary arts. Until recently the hotel had operated a restaurant, which now is open for private functions only.

The view from our deck off Chambre Monet, at Hostellerie du Cheval Noir, Moret-sur-Loing

We were greeted by Gilles’s wife Anne Bourdeau, who led us the winding stair to select a room. Kathie had booked the Sisley room, decorated with copies of the master’s work by a local artist. For a few Euros more, we could have the larger Monet room. Both had decks facing north, with en-suite bathrooms. Dragging our bags up the wooden staircase, we collapsed for an hour, pondering our next move.

Stalking Eliza Greatorex, we had come to Moret to locate her final abode. Having only a description by an American woman, in a letter written in 1909 to her sister about calling on Eliza’s daughter Kathleen. The other clue was a short description of the property by Kathleen’s sister Eleanor, who had died in 1908. Surviving letters bear the return address of “Ramparts”. As we soon would discover, most of the town is encompassed by twelfth-century walls, punctuated by cylindrical towers. With less than two days to solve the mystery, we embarked on our adventure by heading to the nearest café.

(to be continued….)

Poret de Samois, Moret-sur-Loing. Ile de France

Opening onto the roof-deck, the French window welcomed a cool breeze into the room. We awoke from our nap just around eleven, on the twenty-four-hour clock. We gathered out wits and debouched from Hostellerie du Cheval Noir into Place de Samois—a small square consisting of small wooded car-park to the south, and a medieval tower to the east, pierced by an arch through which passed Rue Grande—the only straight road in the town.

Monument to Alfred Sisley, Place de Samois. Moret sur Loing

It was Monday. At midday, every shop was closed. We stopped at Le P’tit Moret, a creperie on Rue des Granges. The door was open. Music was playing. Chairs were set out on a deck across the narrow street. Calling out to see if the place were open, a young man emerged from the kitchen who told us they would not be serving until noon. Wandering down the street, we emerged onto Place de l’Hotel de Ville—a wide, open square with a gentle incline, paved with flagstones. The city hall resembled a large stone house, next to which stood a timbered building with a glazed storefront, occupied by Les Amis de Sisley, a local society celebrating the legacy of the Impressionist painter who lived and died in Moret. Along Rue Grande, we noticed people sitting at a cluster of umbrella-tables consuming something. Beside them rose a Great War monument—a sandstone private standing at parade rest, honoring the battle-dead of Moret.

La Maison des Arts, Place de l’Hotel de Ville, Moret sur Loing-et-Orvanne

Place de l’Hotel de Ville, Moret. Exterior seating for La Maison des Arts

We took a seat. The young, lanky waiter wore his hair long, with a man-bun. He brought us menus, explaining that while no food is served until noon, the bar was open. At that moment, it would be happy-hour in New York. I ordered a beer for me and a Chardonnay for Kathie. Consuming the beverages with relish, we reveled in pre-prandial decadence. At twelve the waiter reappeared, pencil in hand. We ordered a charcuterie plate and another round of drinks. La Maison des Arts is notable in part for the building—a half-timbered medieval revival, built at the turn of the penultimate century. The woodwork, inside and out, had been done by a master carver and cabinetmaker named Racollet. His personal logo was a rat dipping its tail in a glue-pot, a jeu-des-mots on his name. In French, rat is pronounced with a silent “t”. Combined with coller, “to paste”, a homonym of collet, we have Racoller, or Racollet. The artist carved a humorous self-portrait onto one of the wooden pilasters on the façade of La Maison des Arts.

We later were to learn that Racollet had been responsible for a marvelous staircase in the city hall. Lingering over lunch, we reviewed our notes and ordered another round. Like many towns in France, shops in Moret close between noon and 15:00. Here on Mondays they seem never open at all. Strolling back to the hotel, I ducked into the tourism office to obtain a map. The young woman behind the counter knew a little about Sisley but had never heard of Greatorex. She pointed me toward the Sisley monument, a bronze portrait-bust atop a tapering stone pedestal, from which emerged a comely female nude, presumably his muse. Back at the hotel, Anne the proprietress expressed concern about us finding someplace to dine, it being Monday. Her offer to make a reservation for us we graciously accepted. After a catnap, we resumed our reconnaissance by returning to the Place de l’Hotel de Ville along Rue des Granges. Next to the post office we passed through the northern gate, which was crowned with a pitched roof and ornamental cupola.

The North Gate, Moret sur Loing

Sandy lot behind the post-office, with a fragment of the ancient wall.

12th-c. perimeter wall, Moret sur Loing

The street—Cour de Couvent, led us to Rue du Peintre Zanaroff, with a car-park across the street, with a park off to the right. Running parallel to Rue Zanaroff on the near side of the street stood a section of the twelfth-century wall, dressed at one end like it had been sliced clean through with a knife. We had found the ramparts. Examining the medieval wall, we were stunned not to find them more stoutly built. Shortly after their construction, the structure would have had a timber walkway near the top, for defenders to occupy in repelling attacks. Below that perhaps one might find modest shops, ateliers and dwellings. Nothing remains today except for the wall, covered with ivy.

At its interior base, a driveway led back to a residential garden where a woman stood talking on her mobile. As the Greatorex women had lived near the ramparts, I saw no harm in asking a local if they had any knowledge or oral tradition remembering three American women living nearby. As I walked up the driveway, a man on a motorbike came up behind me. I explained the nature of my quest, but neither had ever heard tell of American artists living in town. Only Sisley. We continued to follow the wall, peering into gardens, comparing what we beheld with the handful of lines describing the Greatorex property as being by the ramparts, with a small tower nearby, a large studio building which they once tried to rent to Rodin. We walked toward the Loing, around yet another round tower, into a riverside park known as Le Pre Magaron.

Kathie entering Le Pre Magaron

Houses built into the perimeter wall along Le Pre Magaron

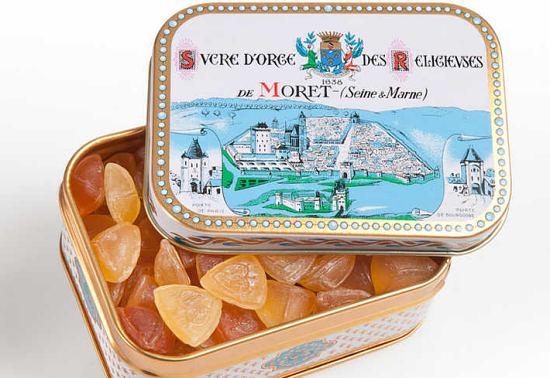

The scholar pauses to reflect

Here the enclosing wall stretched southward, toward the bridge and the Porte de Bourgogne. A number of properties could have fit the bill. Many were built into the remnants of the old city wall. East across the river stood the reconstructed mill. The river Loing empties into the Seine about a kilometer to the north. In the middle of the span is an island, upon which stands a reconstructed mill. The original Moulin Graciot, which had stood for hundreds of years was blown up, along with several arches of the ancient masonry bridge, when German troops withdrew from the town in August of 1944. Another mill along the south side of the bridge—Moulin a Tan has been refurbished to serve as an art gallery, while yet another mill now houses the Musee du Sucre d’Orge des Religieuses de Moret (Moret Museum of Barley-Sugar of the Religious). The shop selling the candies stands opposite the Church of Our Lady of the Nativity (l’Eglise du Notre Dane de la Nativite), on Rue du Puits du Four.

Moulin Gratiot and Pont de Moret

Looking west beneath the bridge to the Quai des laveuses, the low doorway to the staircase beyond

High-water marks recording various flood levels over the century, Quai des Laveuses

Passing below the bridge we came to a series of small waterpower dams, beneath a canopy of trees. The city wall soared overhead. A couple of young women sat huddled at the water’s edge. The paved esplanade known as Quai des Laveuses narrowed to its terminus, where an elderly lady was seated, lost in thought. Backtracking, we came to a low opening in the base of the wall behind a large stone. The doorway gave access to a covered way in which a stairway inclined steeply upwards. A gap between two buildings covering the stairs admitted some light. Aerosol paint tags on the passageway’s dingy yellow stucco walls may be graffiti, but calling it art would be a stretch.

Kathie on the stairs at Quai des Laveuses

Escalier Royal, between Rue de Tannerie and Rue du Donjon, Moret sur Loing.

We debouched from the tunnel onto Rue da la Tannerie. Walking south we considered the likelihood that any of these properties was the one described by Eleonore Greatorex, or her friend Miss H. Coming to a dead end, we undertook another narrow ascent. In contrast to Quai des Laveuses, Escalier Royal was open to the heavens. Climbing the steps to Rue du Donjon, we turned south to approach the castle-keep. Satellite views show formal gardens and other structures behind the walls. The whole town had been built to function as a fortress, and this massive tower was once its beating heart, a final refuge in the event of a siege. Built between 1128 and 1154 in the Roman style, it resembles some Norman keeps found in the British Isles.

The western facade of the Donjon de Moret

Eastern facade of the Donjon de Moret, from the garden

During the 17th century, it served as a prison. Having been arrested by d’Artagnan, Louis XIV’s disgraced finance minister Nicholas Fouquet was incarcerated here at Moret. Beyond the donjon, the street descended precipitously to another cul-de sac. Reversing direction, we came to Rue Monmartre, finding to our left a tall house set back behind a ten-foot wall upon which hung a plaque, identifying it as the residence of the painter Alfred Sisley. Descending Rue du Donjon toward the church, we drifted into a maze of alleyways—some of them no wider than a domestic hallway.

Alleyways, Moret sur Loing

Alleyways, Moret sur Loing

Alleyways, Moret sur Loing

Low stone houses flanking stone stood shuttered and quiet. Returning to Rue de l’Eglise, with an hour to kill before dinner Kathie decided it was time for a snack. She entered l’Echoppe aux Douceurs, a patisserie, while I peered into the window of an art-gallery across the street. At the corner of Rue Grande, we found a bench, where we sat and devoured several rolls. Looking back toward Porte de Samois I saw a woman set out a sandwich-board on the sidewalk. As the sky darkened we made our way back down Rue Grande to L’Entre 2 Ports, a small restaurant specializing in Luso-French cuisine. Kathie and I took our seats on a small deck, perched along the side of the road.

Sitting down to supper at Entre 2 Ports, at the close of a very long day in Moret-sur-Loing

Beneath a blue canvas canopy, plump white lights dangled from electrical cords overhead. Half an hour before, the streets had been deserted. At seven o’clock, small groups of people were seen making their away to one destination or another. Within fifteen minutes the deck that once was ours alone was full of lively conversation. To take our orders, the woman serving us had to stand in the road as cars crawled past behind her. As the sky deepened to an azzurro giottesco our meals arrived. The whole experience conveyed some sense of time-travel. Not because we were dining in a medieval town, or inches away from voitures en passant, but because nearly everyone was smoking, and doing it constantly. Sharing a bottle of light Portuguese wine, Kathie had fish, while I dined on salade de poulpe and maigret de canard. Behind the Porte de Samois the sky assumed first a rosy hue, before blue shifted to a deep purple, above a glorious horizon, glowing red-violet. Walking back through the Place de l’Hotel de Ville we pondered the task ahead, imagining Sisley, Eliza and her daughters treading these very stones, all that remained was to find the place where the peripatetic Greatorex women had finally come to stay, and where the last of them—the beautiful Kathleen Honora–would breathe her last in 1942 at the age of ninety-one.

Porte de Samois at Sunset

Early postcard of Le Hostellerie du Cheval Noir, Moret. ca 1910

Light crept through the gap in the heavy drapes, announcing the new day. Glowing numbers on a digital clock confirmed that we had slept like the dead, well beyond a polite hour for breakfast. As we entered the small dining-room we were greeted by Père de Crick, Gilles’s father. We never caught his given name. Laid out in lavish quantities, our petit-dejeuner was comprised of croissants, sans et avec chocolat, fresh baguettes, butter, crêpes, fresh fruit, yogurt, fromages et charcuterie and strong coffee, all composed in anticipation of perhaps a dozen people or more, yet we seemed to be the only guests in the hotel. Anne arrived as we finished our meal, to inform us that she had left a message of one of the officers of Les Amis de Moret and Les Amis de Sisley, hoping to arrange an appointment for us on the following day. Thanking her we returned to the room, to see to our ablutions and get organized for the day. We left the hotel by the side door on Rue du Peintre Zanaroff, the only door granting twenty-four access to guests of the hotel. If the building was historic, our keys were retro—white plastic perforated punch-cards from the Disco era. The eponymous painter Zanaroff was a late Impressionist named Prudent Pohl (1885-1966), who took the Russian-sounding moniker for reasons as yet unknown to us, and is remembered by the town of Moret by a street bearing his name. Beyond the crosswalk stand the monument to Sisley. Following the painter’s death from throat cancer in 1899, friends of the artist decided to raise a monument in his honor. Sisley’s daughter contacted Auguste Rodin, who agreed to undertake the task, but the committee disliked Rodin’s proposal and instead hired the lesser-known Simeon-Eugene Thivier (1845-1920).

A bronze portrait-bust of the painter crowns a tapering stone pedestal, out of which is seen to emerge a comely semi-nude young woman representing Sisley’s muse. By the time we had revisited the tourism office, acquired a few more maps and brochures, it was approaching midday. Passing through Porte Samois, we proceeded to the Hotel de Ville (city hall) to inquire about how we might research property records. Kathie had determined that both Eleonore and Kathleen Greatorex had lived at a place known only as “Ramparts”, which seems to have been acquired prior to their mother’s death in 1897. After her passing they had tried to entice Rodin into renting a studio on the property, but he ultimately declined. The studio ultimately was leased to the American sculptor George Grey Barnard, who today is famous for the collection of medieval art now housed at The Cloisters in northern Manhattan. Art dealer Sarah Hallowell purchased a property from the Greatorex sisters, where she lived with her mother and niece Harriett. Armed with these tidbits of information, and a few written descriptions of the property by Eleonore and visitors, the trail of breadcrumbs had led us to Moret, but no further.

l’Hotel de Ville from Place de l’Hotel de Ville, Moret-sur-Loing. The half-timbered building to the right houses the Sisley Museum, run by Les Amis de Sisley.

The city hall was abuzz with activity as the town made ready for a European Heritage festival to be held over the weekend. Our landlords Anne and Gilles were distracted by preparations for anchoring a hot-air balloon in a soccer-pitch across the river. A young man took interest in our plight, explaining to the receptionist what we were hoping to accomplish. With a wave of her hand she directed him to a pile of books under the window. One of them was a history of Moret. At the top of one page was the headline Quelques Moretains eminents parmi beaucoup d’autres (Some eminent residents of Moret, among many others). Three names leapt off the page:

Eleonore Greatorex (1854-1909) Rue du Pave Neuf. Peintre

Georges (sic) Grey Barnard (1863-1938) Rue des Fosses. Sculpteur

Harriett Hallowell (1820-1913) Place de Samois. Peintre

Kathie noticed immediately that some of the dates were wrong, and that neither Eliza nor Kathleen Greatorex received a mention. Harriett Hallowell was the niece of the prominent American curator Sarah Tyson Hallowell (1846-1924), who had curated the French art exhibited at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. A new biography of Hallowell by Carolyn Kinder Carr has just been published (July, 2019) by The Smithsonian Scholarly Press. In a letter to a friend dated 1909, Hallowell describes a property she is buying from Kathleen Greatorex as a “…quaint old house, built within the historic walls of beautiful Moret”, mentioning that “Miss Greatorex has her home on the extremity of her property…”

The Hallowell dates published on the Moret notables-list agrees with those of Sarah’s mother, Mary Morris Tyson Hallowell (1820-1913). Despite these errors, we had fresh clues to follow. Writing down the addresses, Kathie and I said our thanks and crossed Rue Grande, taking a table at the now familiar La Maison des Arts. I spread out a map. Kathie took out her notebook. Locating the Greatorex-Barnard-Hallowell addresses on the map, we quickly realized that all were adjacent to one another, or more likely within the same compound. The narrative about a single Greatorex property that had been broken up between 1890 and 1942 suddenly made geographic sense. We were stunned to learn that what we sought had been at our doorstep all along, across Place de Samois from our hotel. Finishing our lunch, we paid the check and walked back to the Hotel de Ville. To the left, a passageway led to a parking-lot beyond which to the south is Rue Pave Neuf (Newly-paved street), presumably the first street in the town to be covered with flags or cobbles.

l’Hotel de Ville, Moret-sur-Loing, from Rue Pavé Neuf

Private garden suspected of once having been the property of the Greatorex women

The city hall’s stately Façade François le 1eme faces the street, which suggests that the present-day Place de l’Hotel de Ville may once have been its backyard. Walking west, the street is lined with small, shuttered stone houses. Perhaps a hundred meters on, the street turns ninety degrees to the right, leading back to Porte de Samois. Passing through, we turned left along the pavement on the western edge of Place Samois. Dead ahead, driveway led to a green wooden gate. Behind it we could see a garden, with yet another fragment of the old city walls. Ivy crept up the side of a round tower. Had we reached our goal? The setting matched the descriptions we had. The published addresses had brought us to this place. Somehow it did not feel like enough. Ramparts were everywhere. A postman would have to be psychic to know to which ramparts he should deliver a letter to the misses Greatorex. We wandered over to Rue des Fosses, the street given as Barnard’s address. Just then a man emerged from the house on the corner. Turning to him I asked if he had heard the name Greatorex, or if he knew anything about American women living here during the last century. He thought for a moment, and said that he did remember hearing something, about a time long ago. There was someone he knew, who perhaps might be able to help.

Kathie looking at the houses along Rue Pavé Neuf

He led us back to Rue Pavé Neuf and knocked on the door of one of the stone houses. The top half of the door swung open. He described our mission to the elderly woman, who replied bien sur! Her parents had purchased the house from Harriett Hallowell sometime around the Second World War, and that Hallowell and another old American woman had been living together but that both had died during the war. All the pieces began to fall into place.

Kathleen must have taken possession of the house when Eleonore died in 1908, and then sold it to Sarah Hallowell. Kathleen Greatorex must have broken up the rest of her property over the years, finally entering into a domestic arrangement with Hallowell. Nothing is known about their lives under the Nazi occupation. On her death certificate, the date of Kathleen’s death is given as May 6, 1942, the cause simply as “old age”. Her sole heir was Harriett, who died the following year. We knew we were close. All that remained was to find their home, “the Ramparts”, or whatever remained of it.

Kathie Manthorne. Boots-on-the-Ground art historian, with a bag full of barley candies. Since people will ask, the polychrome Oxfords are by Camper, acquired in June at On Your Feet in Santa Fe, New Mexico

Backtracking past the city hall, we walked along Rue Pave Neuf until we came to Rue de l’Eglise. Kathie had decided that we urgently needed to acquire a quantity of the famous local barley-candy for future use as gifts. Previous attempts to visit the shop had found the place closed. Turning right onto Rue de l’Eglise, we walked uphill a few blocks to the church. Beyond it on Place Royal we espied our objective, lo and behold–open for business. A painted stone cameo framed in carved heraldic scrollwork, announced that Sucre d’Orge Religieuses de Moret had been in business since 1638. These sweets were first produced in Moret by Benedictine nuns, although their origins surely date to a much earlier time. De Lis Chocolat has preserved its historic appearance, behind a half-timbered shop-front. Wooden shelves and countertops were piled high with sucker-candies, packaged in everything from small sacks to colorful painted tins. An attractive matron stood at the ready, to assist shoppers and take their payments.

Des Lis Chocolat.Boutique Sucre d’Orge des Religieuses de Moret. Rue de l’Eglise and Place Royale, More sur Loing, Ile de France.

Our first mission accomplished, we seized the opportunity to visit the church. Finding it open, we entered and lit candles in memory of the recently departed. Notable for its historic pipe-organ, l’Eglise de Notre Dame de la Nativite is a cathedral in miniature, with soaring vaults above light-flooded spaces. Construction began in the 12th century, around the same time as the Donjon and city walls. Suffering physical damage during the revolution of 1789 and employed for a variety of secular functions for the duration. It served as a subject for a number of paintings, including one by J.B.C. Corot, and later by Alfred Sisley, whose house stands around the corner and up the hill. Today the church serves an active congregation as a place of worship, and the general community as a concert venue.

View of Moret by J.B.C. Corot. 1822

The Church at Moret by Alfred Sisley. 1894. The view is from the corner of Place Royale looking north along Rue de l’Eglise, next to Boutique Sucre d’Orge

Jeune Chasseur 1880. Watercolor on paper-board. Kathleen Honora Greatorex (1851-1942) The hunter is dressed for the field, wearing a short roundabout jacket and stout knee-gaiters. Holding a hunting-horn, a cloak is thrown over his left arm. Long flowing hair adds to an effeminate romantic appearance, completely unlike Courbet’s rustic killers. One wonders if the sitter is male.

According to Kathie’s research, Kathleen Greatorex had a close and possibly intimate friendship with Sisley near the end of his life, buying his paintings to provide some financial support. Her grandfather had been a Methodist circuit-preacher. In spite of that, and her own Anglican upbringing, Kathleen Greatorex must have shared her mother’s ambivalence about sectarianism. Eliza Greatorex once had an audience with Blessed Pope Pius IX, and had become a close friend of the parish priest during her sojourn in Oberammergau. Contemporary accounts characterized her beliefs as more spiritual than religious. We had come to Moret to find a piece of real estate. We also found ourselves walking in the footsteps of three remarkable expatriate women, whom we had come to know over the years. We stood in the nave. Light streamed through the windows. A chill ran up my back. For a moment, I had the feeling that were I to turn around, they would be there behind me. Having accompanied Kathie on many research trips in search of Eliza Greatorex and her daughters; to Cragsmoor, Ireland, Bavaria, Manitou Springs and now Moret-sur-Loing, nowhere else had I felt their presence so palpably. Throughout the process of reassembling their lives into a coherent narrative, Kathie had been challenged at every turn. Eliza Greatorex once said, “I hate to write letters”. What personal correspondence she left behind is scattered through a variety of private and public collections. Much of the factual details of her biography is drawn from newspaper articles and accounts left by others. Like many Irish parents, she kept her children close. Supporting Eliza’s enterprise in many ways, the daughters never married perhaps because they were always doing her bidding. By the time they had reached Moret, Eliza was slowing down and both of her girls would have been considered old maids. Having come this far, we decided to take a final pass at reconfirming the location of their residence, on our way back to the hotel.

Upon leaving the church we turned left, walked south up Rue de l’Eglise, to its intersection with Rue des Fosses at the top of the hill. Here we turned right, heading back toward Place de Samois. I had the idea that perhaps we might get a glimpse behind the walls, in order to get a better sense of the scope of what we now believed to have been the Greatorex establishment. The only confirmation we had received so far concerned the modest house on Rue Pave Neuf. Questions remained. Where was George Barnard’s studio, that almost was rented by Rodin? Where was the garden described in letters written by Eleonore Greatorex and Sarah Hallowell? Where were the boundaries? What was the extent and configuration of the property? We passed Rue du Clos Blanchet, which led back to the labyrinth of alleyways we had explored on Monday. Rue des Fosses then veered to the right. At the foot of the hill I recognized the now familiar Place de Samois, our final destination. Rooftops were awash in golden light, like the church in a painting by Sisley. Across the street a woman collected her mail. We asked if she knew anything about a group of American women artists living nearby, long ago. She shook her head. When I mentioned the word “ramparts” she replied “la”, pointing to a rough stone wall with a garage-door, painted green. Next to it was a shuttered building with pitched roof and brick chimney that a real-estate agent might call a cottage. In a letter to a friend in 1909, Sarah Hallowell mentioned that “…Miss (Kathleen) Greatorex has her home on the extremity of her property”. If she had sold the house on Rue Pave Neuf to the Hallowells, and was renting buildings to the likes of George Barnard, where had her residence been located? At the far end of the facade was small arched doorway. Just beyond that, set back atop the wall that runs along the sidewalk, was a small stone plaque into which was set a mail-slot. On its metal flap was inscribed “STOP PUB MERCI” (No junk-mail please). Onto the stone surface above the mail-slot was carved: LES REMPARTS. (The Ramparts). Could it be?

Craning my neck, standing on my toes, I peered over the wall to behold a beautiful sunken garden, enclosed by stretch of the old city walls. It was just as Eleonore had described it, like an amphitheater. At its southern end stood an elegant home, tucked up behind the smaller building that faced Rue des Fosses. The street was on the same level with the second floor of the main house, or the premier-etage if one starts counting above the ground floor. Making note of the name on the doorbell we made some inquiries and discovered that the current residents treasured their privacy, which we were eager to respect. In just two days, our goal of discovering the final residence of the Greatorex women had been achieved. Astonished by our luck, we marched down to the Cheval Noir, where Anne informed us that a meeting had been arranged for us the following morning with Les Amis de Moret and Les Amis de Sisley. Anne then made a dinner reservation for us as the creperie next door. With a couple of hours to kill we returned to our room, opened a bottle of wine we had been saving, settled ourselves on the deck, and took stock of the day.

Rooftops of Moret at Sunset, from the deck behind the Chambre Monet above Courtyard of Hostellerie du Cheval Noir

Our final day in Moret began with another fabulous breakfast at Hostellerie du Cheval Noir. Our host Anne had arranged for uys to meet with three gentlemen who represented the organizations Les Amis de Moret and Les Amis de Sisley. None had ever heard of Eliza Greatorex or her daughters. We shared our research with them, and were informed that according to local lore, a number of medieval statues, and a capital from a column in one of the nearby churches had been purchased by an American artist for a museum in New York. Kathie explained that the artist in question was George Grey Barnard, (1863-1938) whose collection now forms the core of the Met Cloisters. We unpacked the tale of finding Les Remparts, diplomatically inquiring if the present owners of the property might welcome a call. We were discouraged from pursuing the idea, as the owners put great stock in their privacy. It was enough to know that we had indeed located the former Greatorex abode. Kathie had discovered that Auguste Rodin nearly rented a large studio on the property that later was rented by Barnard.

Standing Virgn and Child. France (Moret sur Loing). ca 1300-1350. Met Cloisters, New York.

With the officers of Les Amis de Moret and Les Amis de Sisley, in Moret sur Loing. Ile de France. Left to right: Christian Lecoing, James McElhinney, Kathie Manthorne, Luc Paylot, René Roesch.

Christian Lecoing, who spoke very good English, expressed interest in learning more about Greatorex, not only because of her daighter Kathleen’s friendship with Alfred Sisley. but because of her activites as part of the plein-air etching movement. Kathie shared that Eliza not only kept a place in Paris, near the Jardins de Luxembourg, but that she had also embarked on sketching excursions to Cernay-la-Ville, and Chevreuse, today a ninety-minute drive from Moret. It seemed that the town of Sisley might have yet another artist to feature along the Routes des Peintres, a project celebrating the travels of Impressionist painters. We learned hat apart from establishing partnerships with towns along the Impressionsims Routes, Moret operated an artist residency progam through a cultural exchange with Sichuan, China. The story goes that one day a Chinese painter set up an easel on the banks of the Loing and one thing led to another. Everyone was under time constraints as the whole town was busy getting ready for the annual European Heritage festival on the weekend, and we had a train to catch. Following an exchange of contact information, we crossed the street for a photo opportunity at the foot of the Sisley monument. While we had hoped to locate the graves of Eliza and her daughters, we had no time to spare. Luc drove us to the station. We all promised to keep in touch. Arriving in Paris, we discovered our hotel reservation (and those of others scheduled to speak at the symposium) had, through some administrative mishap, been cancelled by Centre Pomidou. How Musee d’Orsay came to our rescue is a tale for another day.

The grave of Eliza Pratt Greatorex (1819-1897) Cimitiere Municipal de Moret-sur-Loing, Moret-sur-Loing et Orvanne, Ile de France.

Photograph courtesy of Hans-Christian Bohlmann, who upon reading my account of our visit to Moret kindly wrote to us, attaching photographs of the graves of Eliza, Eleanor and Kathleen. Had we visited the cemetery we would have found them next to the town’s most famous resident Alfred Sisley. Given the closeness of his relationship with Kathleen during his final years, and her generosity toward him in life, it is possible that she continued to be his benefactor in death. The proximity of their graves is unlikely to be a coincidence. We wish to extend our heartfelt thanks to Monsieur Bohlmann, and other kindlyMoretains who assisted our quest including Anne Boudreau, Gilles de Crick, Christian Lecoing, Luc Paylot, René Roesch, the wonderful staff at the Hôtel de Ville and others…many thanks!

NEW BIOGRAPHY OF ELIZA PRATT GREATOREX by KATHERINE MANTHORNE

This inspiring book rewrites the history we thought we knew about women artists in 19th-century New York. Rediscovering a life once described in the national press as among the most important women in American history, the author also brings other lesser-known women into the canon. Unlike privileged woman like Mary Cassatt, Greatorex was born in Ireland, the daughter of a Methodist circuit-preacher, who through personal industry and restless entrepreneurship managed as a widow to raise four children, while building a stellar career as the foremost American woman-artist of her age. In researching this book, Kathie retraced Eliza’s journey from Ireland to New York, to Munich, Oberammergau, Colorado and Paris.

Having been on a number of these expeditions, and having read every page more than once, I can say that many surprises await the reader. This is not just an academic biography. It’s a page-turner. I know these are cliches, but Eliza’s story will have you cheering. You will laugh. You will cry. You will be inspired.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Linkedin

Linkedin