Waiting for the crisis to pass, our thoughts go out to friends and loved-ones who also shelter in place. Old friends pass away, people we loved and admired. Immobilized for the time being, we can revisit destinations, near and far. join me in celebrating the joys of Quaranteam travel, the hope that these diversions might inspire us to value things we had taken for granted, to draw strength, wisdom and compassion from deeper engagements with nature.

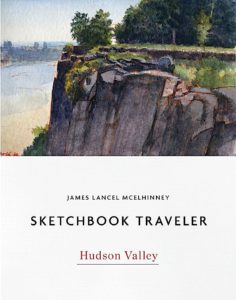

Looking South from Fort Lee. Saturday September 10, 2016.

. (Image and text were featured in the exhibition James McElhinney. Discover the Hudson Anew, curated by Laura Vookles. Hudson River Museum. Yonkers, New York. September 13, 2019 to February 16, 2020. Published also as a limited-edition in Hudson Highlands. North River Suite Volume One. Needlewatcher Editions. New York. 2018)

“The view from the high point…of Fort Lee is extensive and interesting, up and down the river. Across are seen the villages of Carmansville and Manhattanville, ad fine country seats near; while southward, on the left, the city of New York stretches into the dim distance, with Staten Island and the Narrows still beyond. On the right are the wooded cliffs extending to Hoboken, with the little villages of Pleasant Valley, Bull’s Ferry, Weehawk, and Hoboken, along the shore.”

–Benson J. Lossing. The Hudson From the Wilderness to the Sea. 1866

The southern end of a basalt diabase sill known as The Palisades had been fortified in the summer of 1776, in anticipation of an invasion by British Forces. Armed with several batteries of cannon, the earthen fort projected fields of fire across the Hudson to the east, while Fort Washington stood on the highest point on the island of Manhattan, its guns facing westward. A chevaux-de frise of sunken ships stretched in a row across the river, from Jeffrey’s Hook to the foot of the cliffs below Fort Lee. Today’s George Washington Bridge stands directly above the remains of this obstacle. On November 16, 1776, a helpless and frustrated George Washington looked across the river, to observe British and Hessian troops overrun the fortification that bore his name. On November 20, Charles Lord Cornwallis led British regulars up a cleft in the escarpment to cut off Washington’s line of retreat. The maneuver failed. Thirty-four days later Washington and the remainder of his army surprised and captured the Hessian garrison at Trenton, New Jersey, striking a blow for independence.

Troops under Charles Lord Cornwallis scaling the Palisades on November 20, 1776. Watercolor by Thomas Davies.

Collection of New York Public Library. (Reproduced here under fair use, etc.)

The Lenni-Lenape called the Palisades Weehawken: “rocks that look like trees”. On a grassy ledge, just north of the western portal of the Lincoln Tunnel, Vice President Aaron Burr mortally wounded former Secretary or the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in a duel fought on July 11, 1804. The site is six miles downstream from this overlook. The southern end of Fort Lee State Park is marked by a steep declivity, a break in the sheer precipice that girds the western bank of river.

Benson J. Lossing. View from Fort Lee. 1866

Across the Hudson river, northern Manhattan landmarks like Riverside Church and Grant’s Tomb are visible, with the towers of Midtown and Lower Manhattan beyond. A pair of Asian women speed-walked along the park trail behind where I was painting.

A century earlier, Fort Lee had become a major center of motion-picture production. William Fox established Fox Film Corporation in 1915. Young Thomas Hart Benton worked in Fort Lee as a scenic artist. Film crews shot cliffhanger endings along the Palisades, for serials like The Perils of Pauline starring Pearl White.

Despite the sylvan setting, there was a constant roar from the bridge. Nearly four hundred vehicles cross the bridge every minute, spewing legal emissions. On the day before the fifteenth anniversary of the attacks on the World Trade Center, there had been a piece in the news this morning about an apology by former New Jersey governor and EPA chief Christine Todd Whitman for saying that the air around Ground Zero was safe to breathe, just days after the 9/11 attacks. The mercury hit ninety. Humidity levels cast a haze over the city, flattening the distant skyline into a pale silhouette. A teenaged couple hovered nearby, before wandering over to the precipice. Leaning against the guard-rail, they started making out. I can take a hint.

People mistakenly imagine that painting from observation is just a prolonged a snapshot.

All of the most important decisions regarding composition and color I had made on Saturday (September 10). Returning on Thursday afternoon (September 15) the park was abandoned, except for two Korean women speed-walking laps on the park-trail. They had paused before, to look at me from afar. This time they slowed to a halt, then wandered up to peer over my shoulder. I looked up and smiled.

They smiled back. “Any questions?” I asked.

“Yes” said the older one. “Are you married?”

Check out April 2020 Quaranteam Traveler Dispatches

(A preview of SKETCHBOOK TRAVELER by James L. McElhinney (c) 2020. Schiffer Publishing).

Copyright James Lancel McElhinney (c) 2020 Texts and images may be reproduced (with proper citation) by permission of the author. To enquire, send a request to editions@needlewatcher.com