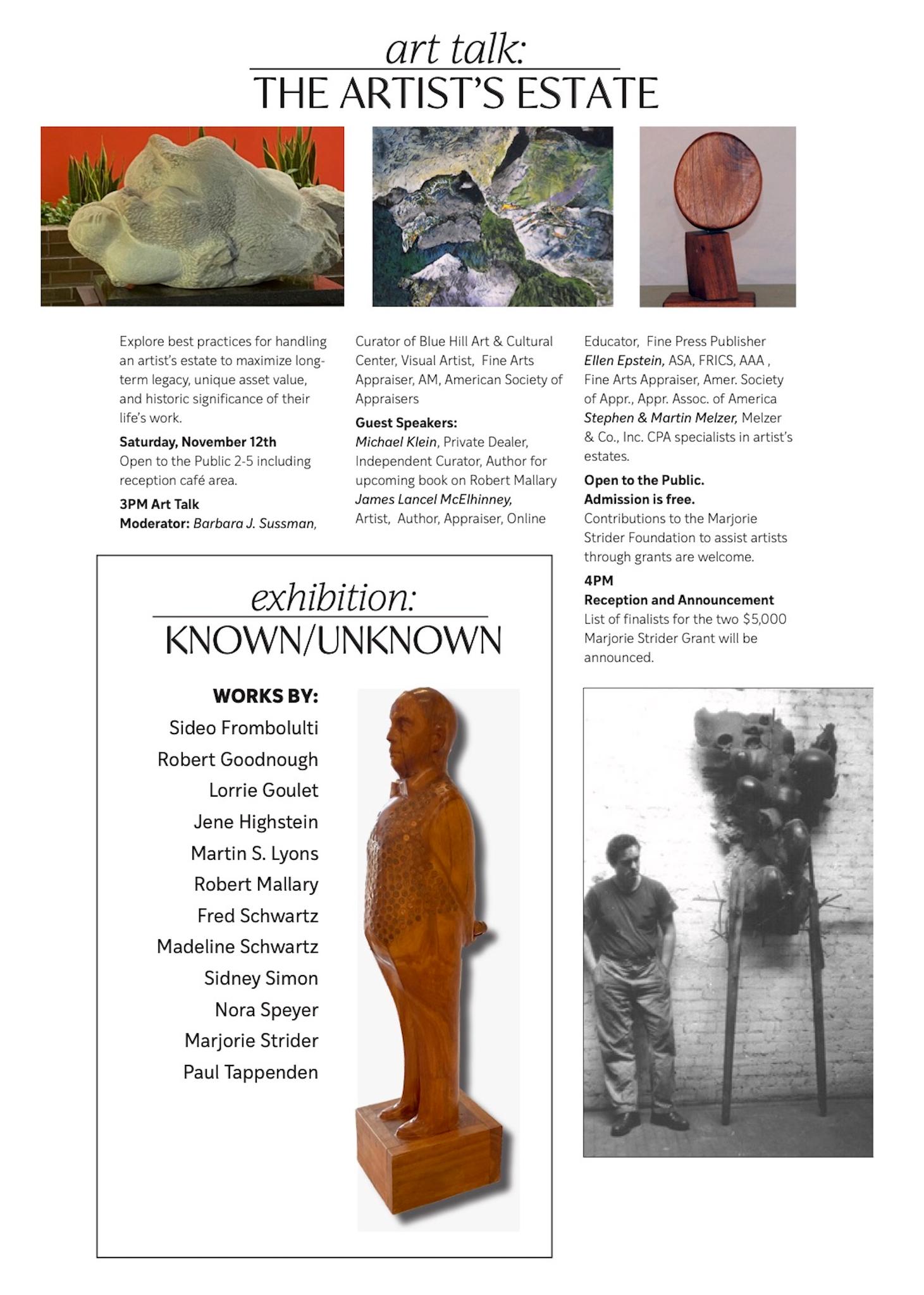

(Preliminary comments I delivered at Art Talk/The Artist’s Estate; a panel discussion held in conjunction with the exhibition Known/Unknown: Artists’ Estates, at Blue Hill Center for the Arts in Pearl River, New York. November 12, 2022.)

“It’s great to be here. I would like to extend my hearty thanks to Blue Hill Art & Cultural Center, the Marjorie Strider Foundation, and Barbara Sussman of Fog Hill & Company, for giving me an opportunity to address you all today. I’ll try to keep my comments brief.

Let me begin by telling you a story, Exploring a wooded island-chain in the vast waters of Secaucus Bay, hundreds of years in the future, a team of archaeologists makes a startling discovery. Boring down into sylvan prominences that once were landfills, excavators bring up cylindrical soil samples. Something captures their attention. At a level corresponding to the second quarter of the 21st century, they notice an anomalous, brightly-colored band—the residue of countless works of art. Other digs yielded similar findings.

A plastic Ziplock bag is retrieved from a former dumpsite near the ruins of Santa Fe. Contained within is a cassette-tape of Terry Allen’s 1979 album Lubbock on Everything. One track holds particular interest. Truckload of Art recalls a highway fatality, when blue-chip artworks worth millions of dollars were consumed in the fiery wreck of a westbound Cab-over Peterbilt 18-wheeler, somewhere in Flyover Country.

Could it be a clue? Why was so much artwork abandoned during such a brief period of time? What could explain this massive surplus? Archaeologists compared their colorful cake-layer to strata from volcanic cataclysms, or fallout from the asteroid-strike that wiped out the dinosaurs. Farmers were known to have plowed under crops in exchange for government subsidies, but what calamity had compelled society to shed so quickly such massive quantities of artwork? Lacking sufficient primary documents to support or refute any of the theories pout forward, the search for clues continues. . .

Before anything like this comes to pass, mankind could be annihilated by a nuclear holocaust or killer plagues. Or—just maybe—artists might wake up to the fact that none of them will live forever, and take steps to preserve their legacies.

In all likelihood, a majority of makers will leave their heirs with a chaotic assortment of objects and papers, with no plan of action for its management. Restrained by sentiment, grief, and vain hope of future sales, the inheritors warehouse these heirlooms at great cost. Decades pass. Nothing happens. Bleeding money, the heirs make the painful decision to get rid of it. Sometime later, one of the paintings comes to light at a flea-market, hanging on a snow-fence. Another sells for peanuts at a rural auction. “Listed Artist” is lettered in pencil, on a paper tag dangling from a loop of thread, taped to a battered frame. The artist’s name rings a bell, but nobody remembers why.

We (Boomer artists) are sailing into a perfect storm. A sea-change is underway in how artworks are produced and consumed. When Tom Wolfe published “The Painted Word” in 1975, he predicted dire consequences, as a result of art-schools and universities flooding the gallery scene with legions of graduates wielding “artist’s statements.” Some of his predictions have come true, but he missed the mark when it came to foregrounding the backstory. Artworks may speak for themselves, but only to those who know how to listen.

While art fairs, auction houses, online sales platforms and social media now provide makers and dealers with many ways to sell art, new hires in studio art at art schools and colleges are in decline. As boomer art professors retire, their job lines disappear. Whole departments are being allowed to vanish through attrition. For the sake of brevity, let’s look at how this small corner of the market is being affected by these trends.

Studio art professors regard themselves as professional artists. The blue-chip art business sees them quite differently, despite the fact that many have been producing and exhibiting artworks for decades. Let’s say that a teaching artist shows twenty works at a gallery. Only ten manage to sell. The remainder are returned to the artist, who squirrels them away; saving them for future buyers, or a pipe-dream retrospective. The problem with this line of reasoning is that it defies real market practices. For example. One consigns an object to be sold at auction. If bidding fails to reach the “reserve”, it is “bought in.” Having been exposed to the market, as an unsold lot it would be considered “burned,” unsaleable for at least a few years, when it might be offered again–in a different market setting, perhaps at a lower price. Publishers release hardcover editions. Some become bestsellers. Others that die on the shelf are remaindered, to be sold at cut-rate prices.

Having taught in higher education for decades, I have come to understand why teaching artists are benighted to these facts of life. They consider themselves exempt. It’s too easy to conflate the meritocracy of academe with market validation, despite the fact that one has nothing to do with the other. A solo show at a gallery could be the equivalent to publishing an essay in a peer-reviewed journal, and thus count toward meeting expectations at one’s day job, and advance their progress toward tenure and promotion. Sales are not part of that calculus. Showing is enough.

But what of those works that came back from these exhibitions? Having been exposed to the market and refused a sale, why are they exempt from the taint of failure—like auction-house “buy-ins,” or remaindered books? The answer is simple. They were made not to be consumed by the market, but to generate academic capital. In other words, most teaching artists are not subject to the rules of the game because they are not on the field. They’re not even in the locker room. Despite this fact, a large number of studio artists working in academe continue to believe that they are shaping culture in durable ways. One supposes they are—by way of the “Butterfly Effect.” What most will accomplish is to be blessed with a creative lifestyle; no small achievement in itself. Unless steps are taken by these folks to establish some kind of durable public legacy; as part of their creative practice, all will be forgotten. It’s one thing to be recognized by one’s peers in one’s lifetime. It’s quite another matter to be remembered by posterity. If the future cannot find you, you were never here.

Let’s do a little math. A painting professor might have had solo exhibitions every two years. Each show featured twenty works, half of which sold. The other half went into storage. Retiring after a forty-year career, the professor find herself/himself burdened with the care and feeding of hundreds of artworks for which no market exists. What can be done? Of course, there will always be dauntless souls who churn out new works until they drop, leaving to their inheritors a chaotic assortment of equipment, papers, sketches, paintings, drawings, and maquettes. Loath to consign all this treasure to dumpsters and landfills, Heirs are often clueless about how to manage it all. What are their options? How might they proceed? Finding answers to those questions is why we are gathered here today.”

(To be continued)