Waiting for the crisis to pass, our thoughts go out to friends and loved-ones who also shelter in place. Old friends pass away, people we loved and admired. Immobilized for the time being, we can revisit destinations, near and far. join me in celebrating the joys of Quaranteam travel, the hope that these diversions might inspire us to value things we had taken for granted, to draw strength, wisdom and compassion from deeper engagements with nature.

Kaaterskill falls. Monday. July 27, 2015

“Why, here’s a fall in the hills, where the water of two little ponds that lie near each other, breaks out of their bounds, and runs over the rocks into the valley. The stream is, may be, such a one as may turn a mill, if so useless a thing was wanted in the wilderness. But the hand that made that ‘Leap’ never made a mill! There the water comes crooking and winding among the rocks, first so slow that a trout might swim in it, and then starting and running, just like any creatur (sic) that might want to make a far spring, til it gets to where the mountain divides like the cleft hood of a deer, having a deep hollow for the brook to tumble into. The first pitch is nigh two hundred feet, and the water looks like flakes of drive snow afore it touches the bottom; and then the stream gathers itself together again for a new start, and may be flutters over fifty feet of flat rock, before it falls for another hundred, where it jumps from shelf to shelf, turning this-a-way and then turning that-a-way, striving to get out of the hollow, till it finally comes to the plain…the rock sweeps like mason-work in a half-round on both, and the shelves over both sides of the hill, and the shelves over the bottom for fifty feet, so that when I’ve been sitting at the foot of the first pitch, and my hounds have run into the caverns behind the sheet of water, they’ve looks no bigger than so many rabbits. To my judgement it’s the best piece of work I’ve met with in the woods; and none know how often the hand of God is seem in the wilderness, but them that rove it for a man’s life.”

–Natty Bumppo to Oliver Edwards, in The Pioneers by James Fenimore Cooper.

Kaaterskill Falls. Benson J. Lossing. The Hudson from the Wilderness to the Sea. 1866. Collection Getty Museum. Reproduced under Fair Use, etc.

I had visited Kaaterskill Falls on numerous occasions. Following the stream than descends from Katers-Kill lakes one reaches a rocky shelf upon which find a large boulder. Climbing upon it I beheld a palimpsest of signatures hewn into the stone by previous visitors, including Hudson River School painter Sanford Gifford. A few feet beyond this glacial hitch-hiker the ground disappears into an airy amphitheater with an audience of thick woods. Opening first to the west, the cleft bends to the south as Kaaterskill Creek crashes down through rocky ravine between South Mountain and Roundtop. In his 1866 painting of the scene, Asher B. Durand has us looking at once from the head of the falls toward the west, and then southeast from the heights near Haines Falls. Someone like Benson Lossing might have detected the cagey old Jersey Huguenot’s bit of leger-de-main, but city swells at the Century Club would have praised it as God’s own truth.

Asher B. Durand. Kaaterskill Clove. 1866. Yale University Art Gallery

In late July of 2016 I returned to Kaaterskill Falls. My aim was to have a look at the new observation platform that had been built for viewing the falls from above. Other structures preceding this one has been built in the nineteenth century. These wooden follies had long ago collapsed into the wooded slopes, indistinguishable from deadfall. Just as contemporary realist painters confuse nineteenth-century verisimilitude with twenty-first century fact, people today imagine Thomas Cole, Durand and other Hudson River School artist roughing it in the mountains like Natty Bummpo and Chingachcook. Nothing could be farther from the truth. By 1830 he Erie Canal had been in business for five years, and Catskill Mountain House for six. The Hudson River bustled with traffic including steamboats landing tourists near sites made famous by Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales. Durand’s 1849 memorial to Cole Kindred Spirits shows not two buckskinned longhunters but refined gentlemen, betogged in the historical-period equivalent of Orvis.

The lookout is reached by way of a well-established trail at the end of Laurel House Hill Road, off North Lake Road in North-South Lake State Park in Haines Falls, New York. Unlike its predecessors the military-grade steel tower is reached by a short bridge at the end of the trail. This adds stability to the vertical structure, which is built on a precipitous wooded slope on the north side of the falls. Unpacking my journal and paint-box I secured the page-ends of the book with small metal binder-clips, clipping the wire elements of one to a lanyard, lest a book full of paintings plummet into the jungle below. Lost in my work, deep in concentration, I heard a voice say, “Excuse me…excuse me.”

Looking up I beheld a pleasant young man in a black frock-coat. With a long-flowing brown beard, bright eyes, yarmulke, and lustrous curling payots, over his shoulders was cast a magnificent striped prayer-shawl. In his hand was a wooden staff, thick as a man’s wrist. He smiled. I smiled back. The last thing I expected to see in the mountains of Ulster County was a Biblical prophet. Stretching out his arm like Charlton Heston in Cecil B. De Mille’sThe Ten Commandments, he pointed to the falls.

“Who made that?” He asked.

Something told me he had never heard of Natty Bummpo, or Thomas Cole.

“Why, God made that” I replied. “God made everything in these woods, except for this tower we’re standing on.”

I went on to tell him the name of the falls was “Kaaterskill”, that “kill” was the Dutch word for a creek. These mountains I told him were once called the Katzenbergs. His eyes lit up. I figured that “Katzenbergh” had a cognate in Yiddish.

“Big cats, panthers used to live in these mountains. Some say they are coming back. Ergo the name. Katzen for cat, bergh for mountain. Now we call them Catskills, which is also the same name of another creek further north of here.”

Suddenly he looked worried. I turned around. A group of Hassidic brethren was clustered on the trail, preparing to depart. The Rabbi scowled and twitched his head as if to say, get away from that evil goy. I bade him farewell as he rejoined his flock.

Other conversations followed. As I was packing up to leave a mixed group of fit sweaty hikers approached.

“Been here long?” one them asked. Three or four hours, I told him.

“We’ve been here all day. Parked down on the road, climbed up the south side of the fall, went up to Sunset Rock and now we’re heading back.”

“Sounds like a great day,” I replied.

“This morning was a bummer,” he responded. “A kid fell off the top and was killed. Teenager taking a selfie. We got there just after it happened.”

“That must have been awful.”

“Hard to forget a thing like that,”

“Amid all this beauty,” I replied

“Yeah, ironic.”

Kaaterskill falls. Monday. July 27, 2015

Check out April 2020 Quaranteam Traveler Dispatches

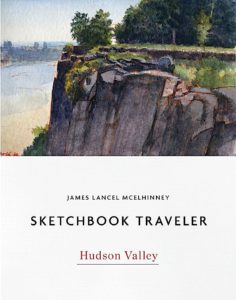

(A preview of SKETCHBOOK TRAVELER by James L. McElhinney (c) 2020. Schiffer Publishing).

Copyright James Lancel McElhinney (c) 2020 Texts and images may be reproduced (with proper citation) by permission of the author. To enquire, send a request to editions@needlewatcher.com