May 16, 2020. Quaranteam Traveler Dispatch #46. Lone Oarsman Passing Three Angels

Waiting for the crisis to pass, our thoughts go out to friends and loved-ones who also shelter in place. Old friends pass away, people we loved and admired. Immobilized for the time being, we can revisit destinations, near and far. join me in celebrating the joys of Quaranteam travel, the hope that these diversions might inspire us to value things we had taken for granted, to draw strength, wisdom and compassion from deeper engagements with nature.

Exploring the banks of the Schuylkill River in 2018, between the mouth of Wissahickon Creek and Fairmount Water-Works I filled a sketchbook with paintings. Later that year, a suite of prints drawn from this journal would become the centerpiece of an installation at Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia.

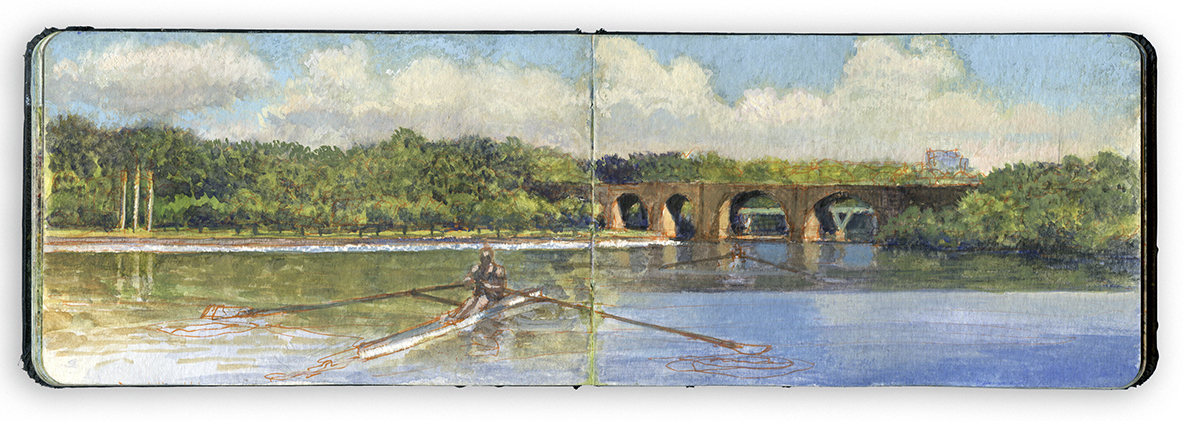

LONE OARSMAN OFF THREE ANGELS

Standing on the western shore of the river near the Dragon Boat Dock, I imagined being in the middle of the river, looking southwest. A lone oarsman moves downriver, not far from where Thomas Eakins portrayed Max Schmitt. Marking a midpoint between bridges on the far shore is the sculpture Playing Angels, completed by Carl Milles in 1950 but not installed until 1972. Widening below Columbia Bridge, the Schuylkill River narrows again as it passes the Pennsylvania Railroad Connecting Railway Bridge. Completed in 1867, the bridge appears in Thomas Eakins’s 1871 painting Max Schmitt in a Single Scull, with an iron Whipple truss as its central span.

Thomas Eakins. Max Schmitt in a Single Scull. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1871. Reproduced under Fair Use, etc.

Five years prior to Eakins’s painting a hydrographoc map of the river was produced. The landscape today is much changed. The Tow-Path and Long Island seen at the top of the image today no longer exist. The channel that once separated the island from the shore was filled to broaden the grassy esplanade.

The railroad following the right bank of the river behind the Tow-Path was rerouted onto a new grade constructed a few hundred yards to the west. The right of way shown on this map was converted first into a carriage-road and later improved for automotive traffic as West River Drive, later Martin Luther King Drive. My location in the journal-painting (39.9828 x 75.2081) above would be along the Tow-Path in the 1866 map, just to the south (left) of a small brook. My directional vector, based on the location of the binding-gutter in my sketchbook would roughly be South 170 degrees. The Schuylkill in Eakins’s day was a working river. Barge-traffic and pollutants such as coal silt from mining operations a hundred miles upriver soiled the waterway, along with effluence from towns and industries upstream. Rowing community old-timers tell of dreading to capsize. Following heavy rainfalls organic waste still tints the river a picturesque orange hue. Water quality has shown dramatic improvement, but silting remains an ongoing problem. The process requires the river to be dredged every twenty or thirty years. I heard tell a story about an bungled mob hit that took place a few years ago. The hoodlum’s feet had been encased in concrete. His would-be killers threw their victim into the Schuylkill, only to have him sink no deeper than his waist. The story may be apocryphal, but it makes a point.

Hydographic map of the Schuylkill River from wire Bridge at Fairmount to Reading Railroad Bridge (Twin Stone). Philadelphia Water Department. Reproduced under fair Use, etc. Note the rolling-mill near the present-day site of Carl Milles’s Dancing Angels (Three Angels) and a brewery where Daniel Chester French’s equestrian portrait of U.S. Grant now stands. Also note the oil refinery indicated on the map, near the future entrance to the 1876 Centennial Exposition Fairgrounds and the Philadelphia Zoological Gardens across Girard Avenue.

Painting in book form presents a few challenges. The binding gutter forces every painting into a diptych format. While this restriction might be seen as an intrusion, obstacle, or vexation, it allows each page to exist in different moments while maintaining a kind of unity. It also serves as a way of determining my line-of-sight in relation to my geographic map-coordinates location (degree altitude x degrees longitude).

During the 1990s, experiments with temporal composites in my paintings of Civil War battlefields relate to nineteenth-century pictorial fictions such as Frederic Church’s Heart of the Andes. None of these journal works is concerned with simple reportage. All of them seek to transform experience into a kind of knowledge that breed ideas.

Working along the Schuylkill near the Dragon-Boat dock. Note the Railway Connecting Bridge in the Distance.

The land upon which I am standing appears in the 1866 map beside the letter g in Long Island.

Check out April 2020 Quaranteam Traveler Dispatches

(A preview of SKETCHBOOK TRAVELER by James L. McElhinney (c) 2020. Schiffer Publishing).

Copyright James Lancel McElhinney (c) 2020 Texts and images may be reproduced (with proper citation) by permission of the author. To enquire, send a request to editions@needlewatcher.com