(First published during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, when Kathie and I were living under lockdown in our Washington Heights apartment).

Waiting for the crisis to pass, our thoughts go out to friends and loved-ones who also shelter in place. Old friends pass away, people we loved and admired. Immobilized for the time being, we can revisit destinations, near and far. join me in celebrating the joys of Quaranteam travel, the hope that these diversions might inspire us to value things we had taken for granted, to draw strength, wisdom and compassion from deeper engagements with nature.

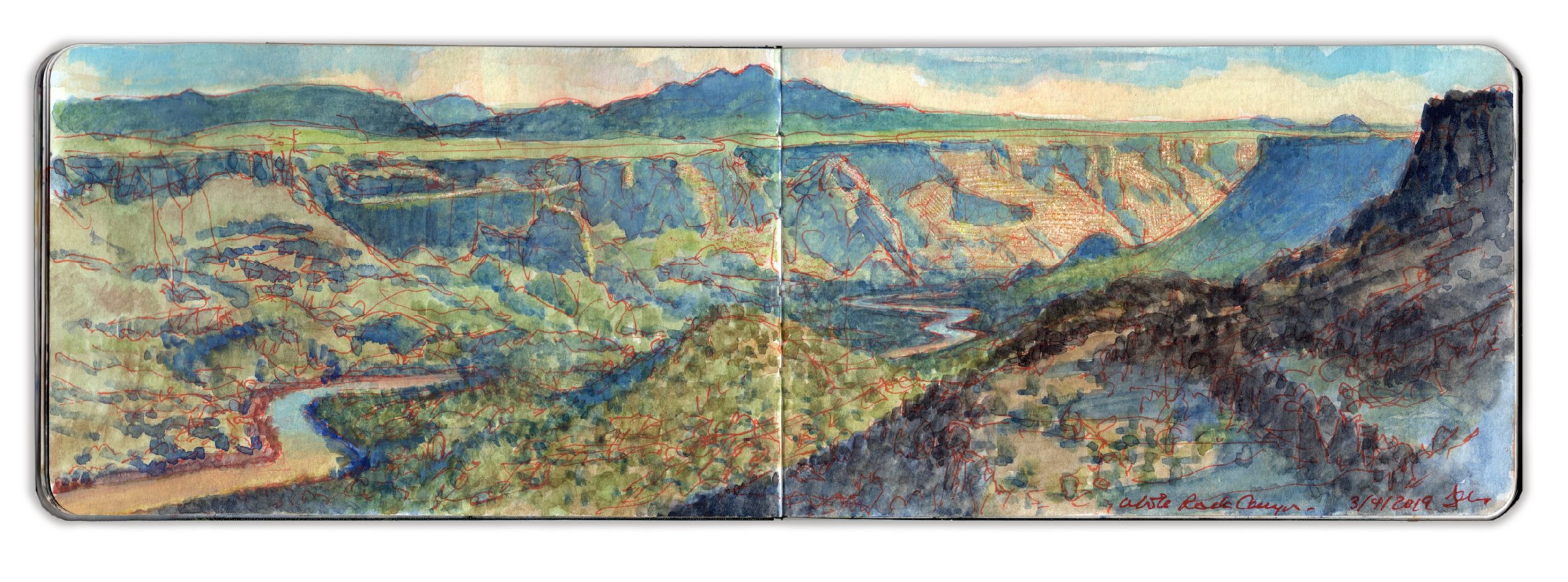

Late Light, White Rock Canyon. March 4, 2019. Looking South from 35.8257 x 106.1810

Traveling to New Mexico early in 2019, I explored the Rio Grande between John Dunn Bridge and Cochiti Reservoir. Sites were selected for narrative reasons, as well as for their visual allure. Many of the works I produced, including my painting-journal, were exhibited at Gerald Peters Gallery in Santa Fe, in the exhibitions Reimagining New Mexico, from June 28 to August 3, and Speaking to the Imagination / The Contemporary Artist’s Book, from June 21 to October 24.

White Rock Canyon is a stunning declivity carved by the Rio Grande through volcanic sediment, running south from Otowi Peak, aka Buckman Mesa. Below Cochiti Reservoir the river snakes across a wide plain, passing Cochiti Pueblo, Pena Blanca, Kewa (Santo Domingo) Pueblo, Algodones and the ruins of Kuaua Pueblo, now interpreted as Coronado Historic Site. Located on the historic route El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, Spanish explorer Francisco Vasquez de Coronado received hospitality from the indigenous people in 1541 before pushing east in search of golden Quivira in 1542. Below Bernalillo the river flows through the northern outskirts of Albuquerque before reaching Old Town below Interstate 40.

Winding through the bottom of White Rock Canyon, the Rio Grande runs narrow and swift. The geology resembles the gorge forty miles to the north, basaltic uplifts towering above heaps of rock-fall ascending from ribbons of greenery along the riverbanks. An old narrow-gauge spur of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad known as The Chili Line stopped at Diablo Canyon, at the confluence of Cañada Ancha, a seasonal creek-bed across the Rio Grande from White Rock.

Steam-powered locomotives were no less thirsty than living things in such a parched land, and thus like El Camino Real, it followed the river. The decision to build a narrow-gauge railroad may have been predicated on water-consumption as much as those challenges presented by terrain.

(Left) Water-tower built for the narrow-gauge The Chili Line of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad, Embudo Station, New Mexico

Descending through Frijoles Canyon in Bandelier National Monument, Rio Frijoles joins the river a few miles downstream. Breaking the horizon, the voluptuous contours of Ortiz Mountain rises up from the distant plain. Beyond it lies La Tetilla (the nipple), a hill just north of La Bajada. (the descent) where the road from Santa Fe to Albuquerque plunges from the rim of the plateau, down into the Rio Grande Valley below Cochiti Dam.

Standing atop the basalt escarpment, open patches of porous black rock are strewn with pebbles of similar porous material. Ascending westward, the terrain rises from high piñon desert through alpine forests to Valles Caldera, a vast mountaintop meadow, once of several located within the crater of a dormant volcano. More than a million years ago the violent eruption of the Jemez super-volcano buried the surrounding area under a pyroclastic flow of ash and rocks. The ground underfoot had been deposited by the cataclysm. Ash-falls spread as far east as the Llanos Estacado (staked plains) of West Texas. As a resurgent lava-cone forms under Redondo Peak, the most visible volcanic activity presents as a concatenation of hot-springs resorts running north into Colorado.

Satellite view of Jemez Caldera (Reproduced under fair use, etc.)

The town of White Rock was hastily built at the canyon’s edge as temporary housing for a growing number of postwar employees at Los Alamos Nuclear Laboratory. By 1957 residents had abandoned the settlement for more permanent dwellings. The site was leveled. By 1962, a growing population motivated developers to build permanent homes on the site of the abandoned town, along with schools, shopping, parks, playing-fields and picnic-pavilions. Trails were developed for hiking that followed the western rim of the canyon-wall. Others descended to the river several hundred feet below. Signs caution hikers to be on the lookout for rattlesnakes. These serpents tend to concentrate in areas that allow them to winter in dens. At sixty-five hundred feet of altitude, White Rock Canyon approaches the uppermost extremity of their range. The first week of March was too early for these predators to be active.

At the northern end of the town is a parking-area and overlook. Looking north one can see Otowi Peak to the right. A mile or more beyond it stands an unmistakable formation known as Black Mesa, where during the Reconquista, indigenous warriors fought the Spanish to a standstill.

People would visit me while I worked. One couple had just moved to Los Alamos from the Midwest. He worked for the Lab. I knew better than to ask what he did.

Another day I was painting half a mile south of the point, on a rocky outcropping. An Anglo couple approached. She seemed much older. Both appeared to be working-class. The man calmly told me that when he was a boy, he and a friend used to comb the canyon for artifacts, looting graves when they found them. His friend still has a couple of skulls on his dresser at home. I asked how he felt about that. He confessed that it troubled him, it didn’t seem right.

I suggested that whatever things he had taken, he better return them. No good can ever come from tampering with the dead. I suggested instead that if he is interested in the indigenous culture, maybe he should read about it, or talk to the people. A better understanding of their ways might inspire more respect. While many depend on fry-bread tourism and the art-market for their economy, any diffidence shown toward non-natives is well-founded.

As on many of my forays, I had begun multiple compositions of different views from the western rim of the canyon. Facing south, I decided to push one of these compositions. Warm sunlight and cool shadows carved marvelous forms in its eastern walls. A large hawk glided past, following the canyon rim. Landing in the piñon-tree beside me, a large crow greets me with a squawk. My keys lay on top pf my field-bag. I put them in my pocket.

(A preview of SKETCHBOOK TRAVELER by James L. McElhinney (c) 2020. Schiffer Publishing).

Copyright James Lancel McElhinney (c) 2020 Texts and images may be reproduced (with proper citation) by permission of the author. To enquire, send a request to editions@needlewatcher.com