Waiting for the crisis to pass, our thoughts go out to friends and loved-ones who also shelter in place. Old friends pass away, people we loved and admired. Immobilized for the time being, we can revisit destinations, near and far. join me in celebrating the joys of Quaranteam travel, the hope that these diversions might inspire us to value things we had taken for granted, to draw strength, wisdom and compassion from deeper engagements with nature.

Cochiti Lake and Dam. Wednesday March 6, 2019. 5:00 pm. Southeast from 35.6361204 x 106.333467

Below White Rock Canyon the Rio Grande flows below table-lands to the east and a series of cañadas to the west—deep ravines clawed into the southeastern slopes of the Jemez volcano, as if by a giant hand. Through these defiles seasonal creeks dump rainwater and snowmelt into the river. One of these—Rito de los Frijoles descends through Bandelier National Monument. Named for noted archaeologist, ethnologist and preservationist Adolf Bandelier (1840-1914), the National Park Service interprets more than thirty thousand acres ranging in elevation from five to the thousand feet. Visible evidence of human habitation spanning thousands of years included Tyounyi ruins and other excavated pueblos, along with modern reconstructions, original cliff-dwellings and petroglyphs.

Winding beneath high bluffs, the river widens gradually. Its flow rate decreases as the current enters the upper reaches of Cochiti Lake. An impoundment of nearly forty million gallons on average, this body of water is created by a large dam built by the Army Corps of Engineers between 1965 and 1973. One would presume that in such a dry country the function of the dam would be water-collection for irrigation. Prior to its construction, the combination of heavy snowmelt and a narrow channel would transform the Rio Grande into a raging torrent. Flooding bottomlands dedicated to agriculture, the damage wrought immense hardship on indigenous communities downriver, such as Cochiti and Santo Domingo Pueblo, and Spanish settlements Peña Blanca and Algodones. These, and other farming settlements up and down the river depended on a system of acequias, water-bearing ditches shared by the community. New Mexicans are by nature friendly and easy-going. In picking fights, a mother’s virtue always works. In New Mexico, water-rights will get you there quicker.

I first visited Cochiti Pubelo in 1980. The lake was seven years old. Unlike today, the reservation was open to public use. Unpaved roads led north to the ash-fields and cañadas below Valles Caldera, or west to the tent-rocks at Kasha-Katuwe, Keresan for white rocks. In 2001 the area was designated a National Monument. Santa Fe County and Albuquerque have over the past thirty years both doubled in population, leading the Cochiti tribe to close its lands to unauthorized visitors. At the same time, one is greeted today by a modern welcome center, café and gift-shop. One of the few areas open to the public is Cochiti Dam.

Driving toward the hamlet of Cochiti Lake I turn right, passing a cluster of tribal utility buildings. Veering right again, I descend a long incline that terminated at a wide-boat-landing with a short dock to its left. A local man stood in the water, wrestling his boat onto a trailer. To either side of the ramp are short stretches of beach. Parking in the lot to the right, I carried my gear across the boat-ramp, sitting down at one of the concrete picnic-tables behind the beach. I am the only non-indigenous person at the site. A young couple sits at the next table, staring into their cellphones. A fisherman walks by, looks at me and nods. Before long my work absorbs me, not so much that I would be grateful for the absence of curious onlookers. One expects diffidence from Native Americans toward European ethnic types visiting Indian land. History has given them no reason to trust our kind. I am mindful also that the lake and its shores are under the control of the Army Corps of Engineers, which adds yet another nervous level to the human layer-cake one finds in The Land of Enchantment.

Richard Hovenden Kern (1821-1853). View of Santa Fe and Vicinity. 1848. Collection New York Public Library. (Reproduced under Fair Use, etc.)

Looking east beyond the dam lie the Ortiz Mountains, which on Dick Kern’s 1848 view of Santa Fe from Fort Marcy are identified as the Placer Mountains. Curious to compare Kern’s rendering of the vista with how it might look today, I went to the ruins of the fort and looked southward.I soon realized that the legend under the historic print was in error. That I was in the right location was confirmed by the presence in Kern’s view of the Martyr’s Cross, honoring the twenty-one Franciscans and numerous settlers killed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. What struck me about the Kern were liberties he took in representing various landmarks in scale. The Sandias are instantly identifiable, as is Cerro Tetilla (nipple hill), and east-facing slopes of the Jemez Mountains to the right. The drawing was more dedicated to identifying specific features of terrain that to a faithful representation of an optical experience.

Frederic Church. Cayambe. Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Oil on canvas. 1858. Gift of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815–1865(Reproduced under Fair Use, etc.)

This same kind of visual jujitsu occurs in Frederic Church’s Cayambe, in which the snowy volcano is portrayed at many times its actual size. Church had done this for visual effect, Kern for calling attention to data.

Gazing across the water, I snapped a photo with my phone. The Ortiz-Placer range was miniscule, barely visible. Taking a page out of the Kern-Church playbook, I enlarge the distant mountains in relation to the lake and dam. An hour before dusk, shadows crawled down the hillside and marched across the lake. Moored to the faraway peaks was a raft of dark clouds, a common phenomenon in these parts. The Sandia Mountains lay shadowed by cloud-banks on many days. Richard Kern’s drawing of Blanca Peak shows a cloud at its summit. Coming through Fort Garland a week before, I had beheld the same sight. Consumed with my task, I failed to notice that everyone had left. A police SUV idled in the parking-lot. Better to leave without waiting to be asked.

Check out April 2020 Quaranteam Traveler Dispatches

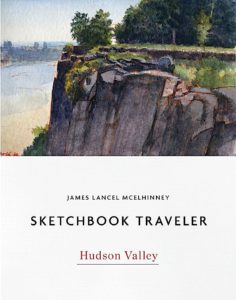

(A preview of SKETCHBOOK TRAVELER by James L. McElhinney (c) 2020. Schiffer Publishing).

Copyright James Lancel McElhinney (c) 2020 Texts and images may be reproduced (with proper citation) by permission of the author. To enquire, send a request to editions@needlewatcher.com