On March 28, 2023 I will be heading to Santa Fe, New Mexico—to participate in the 2023 MONOTHON—a printmaking marathon happening from April 1—8, 2023). Thanks to my loyal patrons who generously underwrote the print sessions!

During my travels, friends will be able to follow me through daily updates and regular live ZOOM meetings from on the road, in the field, and at work in the studio.

SUBSCRIBE. Collectors an opportunity to acquire new monoprints at a significant discount before they enter the retail market.

DONATE via GoFundMe.

WATCH this six-minute video of master printer Michael Costello, owner of Hand Graphics in Santa Fe since. 1987.

James Lancel McElhinney is represented by Gerald Peters Gallery in Santa Fe. For information contact Maria Hajic at mhajic@gpgallery.com

Disclaimer: The GoFundMe campaign is a separate fundraising effort—apart from the collectors’ subscription offer described above. Funds raised by the GoFundMe campaign cannot be applied toward subscribers’ purchase of monoprints, or any other material incentive.

Note: March 3, 2023. I am heading to Santa Fe, to participate in the 2023 MONOTHON—a printmaking marathon taking place from April 1—8, 2023). Follow me with daily updates and regular live ZOOM meetings from on the road, in the field, and at work in the studio. Here are ways to get involved:

SUBSCRIBE. Pre-production offer. Subscribers acquire new monoprints at significant discounts, before they enter the retail market.

WATCH watch this six-minute video for more about the monoprinting process.

Disclaimer: The GoFundMe campaign is a separate fundraising effort—apart from the collectors’ subscription offer described above. Funds raised by the GoFundMe campaign cannot be applied toward subscribers’ purchase of monoprints, or any other material incentives.

In 2019, my travels took me to the upper reaches of the Rio Grande. Over the course of three western sojourns that year, I followed the river from southern Colorado down into New Mexico. Through a mutual friend I met master printer Michael Costello, who since 1987 has owned and operated Hand Graphics; a fine art print studio in Santa Fe.

Over the years Michael has worked with artists such as Carol Anthony, John T. Biggers, Robert Colescott, Luis Jimenez, Forrest Moses, Nathan Olivera, and Emmi Whitehorse. Upon seeing my field-books, Michael suggested that we try a couple of sessions to explore transforming some of the images into monoprints.

What’s a monoprint? Instead of working on canvas or panel, one paints a reversed image onto a plate, then runs it through an etching-press. The result is a painting on paper. Michael and I booked four days in May, and three days in October. Many of our prints used a technique known as Chine-collé—literally “China paste.”

A thin piece of Japanese washi (rice paper) is sandwiched between the plate and the paper with a dusting of powdered adhesive, such as wheat starch. When the print is pulled, the ink sits on this barrier-material, which also contrasts with the whiteness of the sheet. To explore added tension between line and color, I produced several drawings in orange ink, which were scanned and printed onto the Kitakata paper we used in the Chine-collé process. This six-minute video offers a look into our process.

Michael Costello and I will be working together again in April, as part of the MONOTHON SANTA FE 2023; a week-long monoprint marathon, which benefits local print shops, galleries, and youth arts programs.

Monoprints and other works of art are available in Santa Fe at Gerald Peters Gallery, 1005 Paseo de Peralta. Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501. Contact Maria Hajic at mhajic@gpgallery.com, or call +1 (505) 954-5769

Encampment River Winnipeg. Watercolor. 1846

Paul Kane (1810-1871) was born at Mallow, County Cork, Ireland, and emigrated with his family to York (Toronto) in Upper Canada (Ontario) in 1819. Paul displayed artistic talent at an early age. Trained as a sign-painter and furniture-decorator, he received some formal training from a local professor. In 1836 he moved to Detroit, from whence he embarked on a career as an itinerant portrait-painter; traveling through the Midwest and into the Deep South. In 1841, he sailed from New Orleans to Marseilles to commence a walking-tour of Europe that led to Naples, Rome, Bolzano, Paris and London, where he may have met George Catlin—whose Indian Gallery was then on view at Piccadilly. In 1843, Kane returned to The States, where he resumed his portrait business in Mobile, Alabama. He returned to Canada the following year.

Kane’s exposure to Catlin’s work and ideas about Indians as a “vanishing race” grew into an ambitious project of his own; to travel amongst the First Nations of Canada’s western territories, as Catlin had done south of the border. Like the Group of Seven more than sixty years later, Kane began by exploring the wild margins of the Great Lakes in 1845. With support from the Hudson’s Bay Company the following year, he traveled from Toronto to Fort Vancouver, located in present-day Washington State. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 established the boundary between Canada and the U.S. along the 49th parallel north of the equator. Kane was present during the transition period that spanned several years. In 1848, he returned to Toronto. An exhibition of his works was met with great acclaim. Apart from a stint as an expeditionary artist in 1849, Kane spent the remainder of his life in Toronto; raising a family and elaborating his fieldwork into finished paintings.

(Encampment, Foot of the Rocky Mountains. Journal-painting by Paul Kane, ca. 1846-48)

(Encampment, Foot of the Rocky Mountains. Journal-painting by Paul Kane, ca. 1846-48)

Like Thomas Davies in the 18th century, or Tom Thomson and The Group of Seven at the beginning of the 20th century, Kane’s work is rooted in expeditionary practice. As a traveler-artist, he has been described as the first Canadian tourist. Apart from inspiring eponymous parks, schools, and postage-stamps, Kane’s legacy contributed to the national policies concerning cultural resources. In the late 1950s a cache of Kane’s sketches, watercolors and paintings were put on the market by a member of his family. When the Canadian government passed on the offer, the lot was purchased by Texan art collectors Nelda C. and H.J. Lutcher Stark. These works now reside in the Stark Museum of Western Art in Orange, Texas (opened in 1978). Taking heat for allowing these works to slip through its grasp, the Ottawa government enacted laws prohibiting the possession of artworks deemed national treasures, by foreign owners outside of Canada.

(Jasper House. Journal-painting by Paul Kane. 1847)

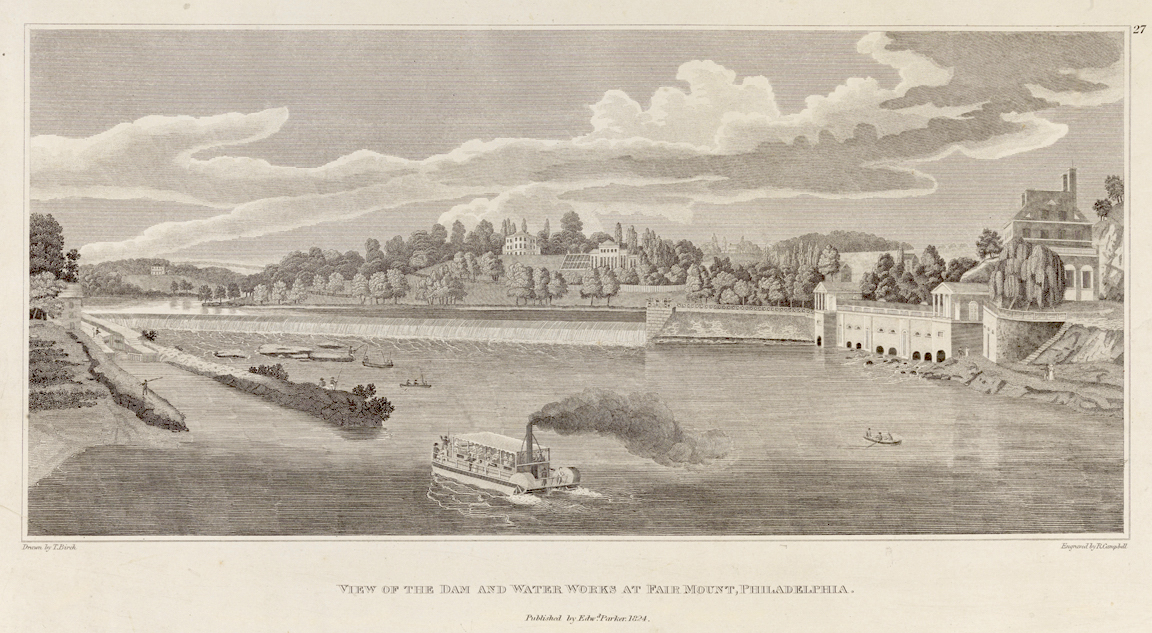

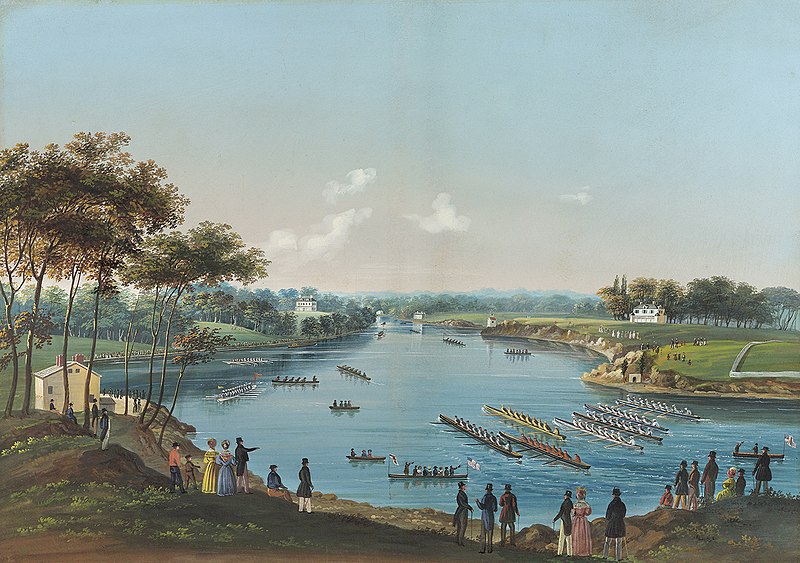

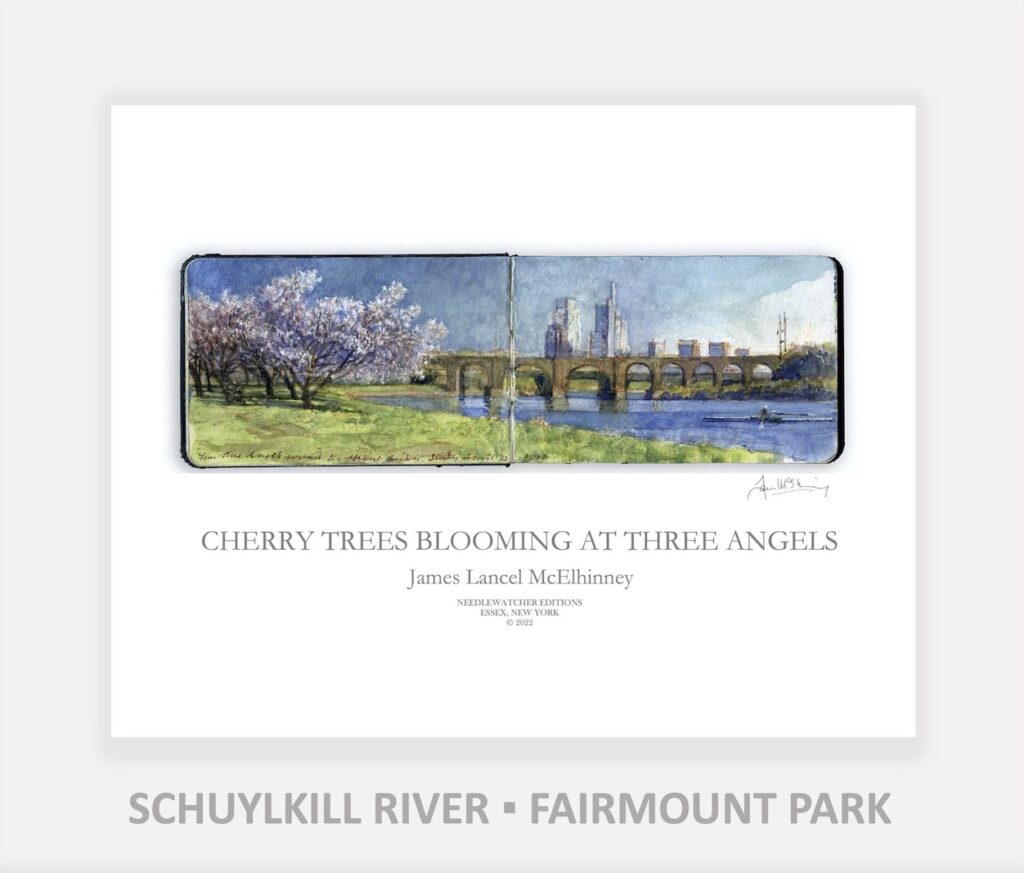

Few parcels of American terrain possess a richer palimpsest of enterprise, memory and desire than does a stretch of the Schuylkill River between East Falls and Fairmount Dam. Its waterworks provided the city with a safer source of drinking water, and a Neoclassical bucket-list destination for tourists. Malarial swamps were buried under broad esplanades. Parklands cobbled together from colonial estates protected the water-supply from industrial polluters. Flat water above Fairmount dam gave amateur rowers an ideal venue for training and competition, while inspiring artists from Birch and Calyo to Eakins and beyond.

Robert Campbell after Thomas Birch (1779-1851). View of the Dam and Water Works at Fairmount, Philadelphia. Collection of Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia PA. (Reproduced under Fair Use, etc.) During the late 18th and into the early 19th-century, Philadelphia was the center of art-publishing in the United States. The city remained a significant force in the publishing industry well into the 20th century. Prints like these with descriptive captions reproduced fine art paintings for popular consumption. Contrary to popular belief these were not necessarily created for wall display. Viewed through contraptions like the Zograscope, used as a form of visual entertainment. The genesis of the American landscape tradition predates the emergence of Thomas Cole as a leading proponent of landscape painting. Prior to his arrival in New York, Cole honed his skills by working in a Philadelphia engraver’s studio. The demand for Grand Tour scenery had been established a century prior, as reproductions of landscape paintings by Richard Wilson, Canaletto, and others. Following the French and Indian War, British military officers such as Governor Pownall and Thomas Davies collected sketches of North American topography that were published in various iterations, including Scenographia Americana in 1768.

Governor Thomas Pownall and Thomas Sandby. View of the The Falls of Cohoes. ca. 1768. Engraved by William Elliot. Published by Bowles, Bowles, Sayer, Jeffrys & Parker. London. Collection Albany Institute of History and Art. Albany, N.Y.

Following the disruptions of the American war of independence (1776-1783), professional artists emigrated to the new republic to capitalize on its natural wonders. William Birch, Thomas Birch, Joshua Shaw, and Samuel Seymour established themselves in Philadelphia. A Yellow Fever epidemic ravaged the city in 1793, motivating civic leaders to harness the Schuylkill River as a safe source of drinking-water. A dam was thrown across the river, at the foot of a large rocky outcropping dubbed Fair Mount. Pestilential marshes that served as breeding-grounds for mosquitos lined the banks that reached back to East Falls. Many were submerged by the rise in water-level. What remained was later buried under broad esplanades traversed by footpaths and carriage-roads. The course of the river was directed through a series of neoclassical buildings at the foot of Fair Mount, into which had been excavated a vast reservoir. William Strickland’s Water Works, and the nearby Colossus (Spring Garden Street) Bridge became bucket-list tourist attractions. In 1835, a group fo amateur rowing-clubs held the first official regatta, which led to formation of a world-class venue for competitive oarsmen, and later; women.

Nicolino Calyo. The First Schuylkill Regatta. Watercolor and gouache on paper. (ca. 1835). Debra Force Fine Art. The painting for many years hung in Castle Ringstetten, the upriver clubhouse of Undine Barge Club, of which painter Thomas Eakins and architect Frank Furness were both members

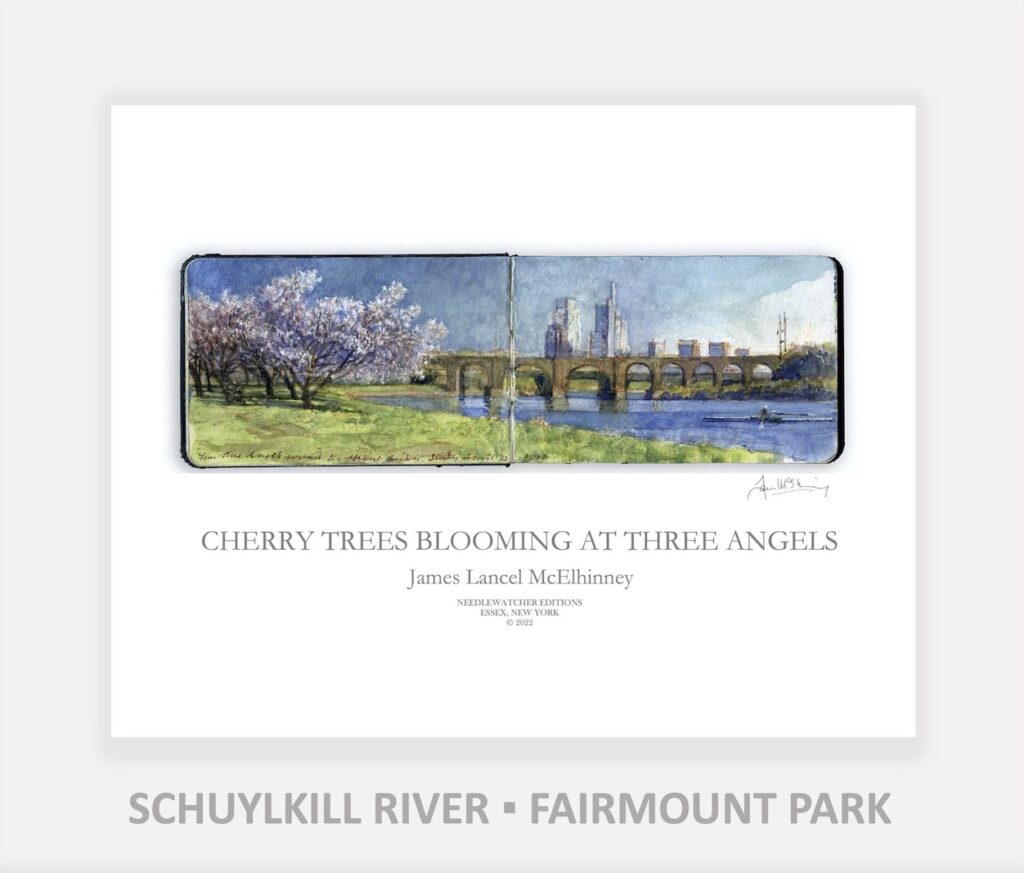

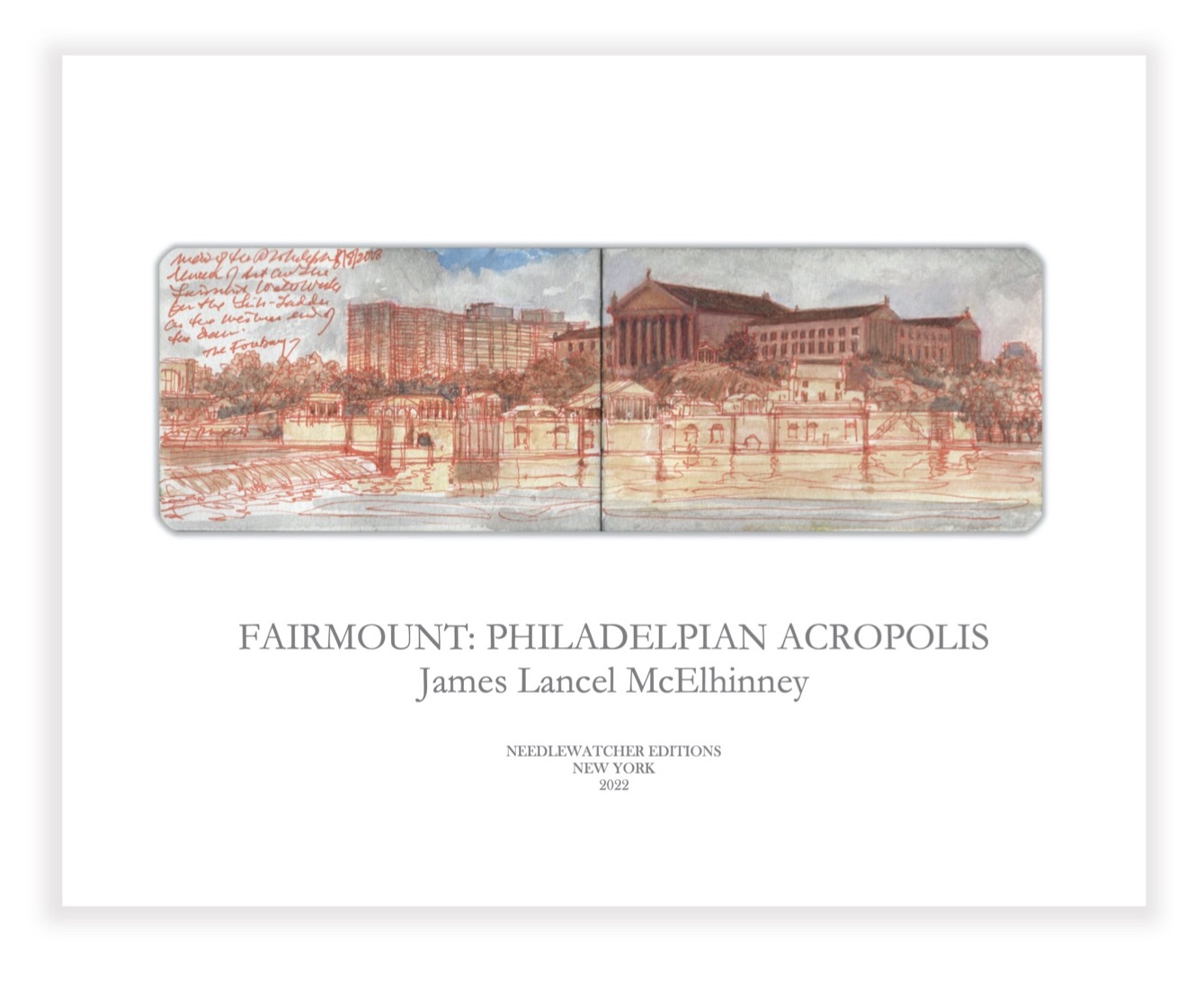

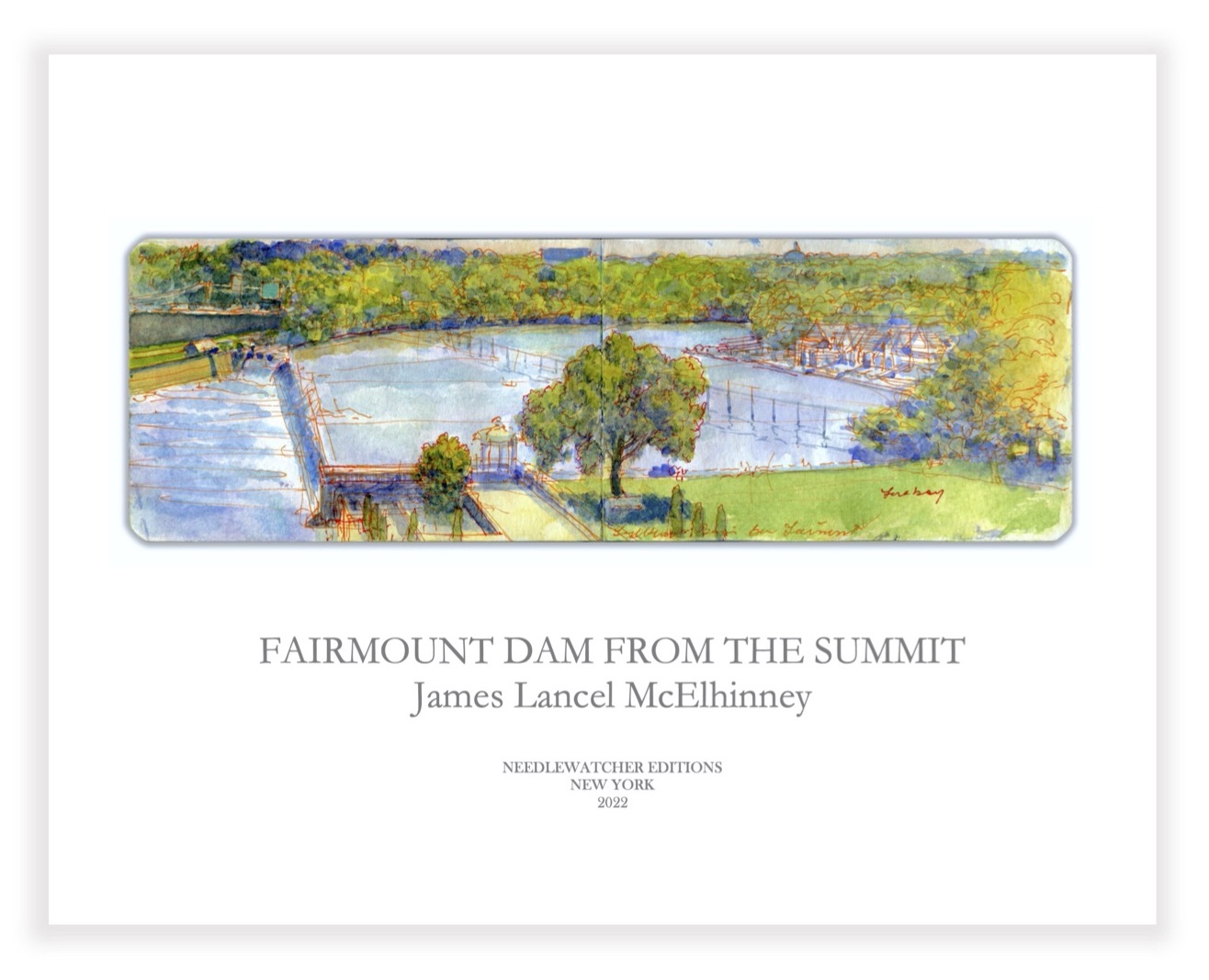

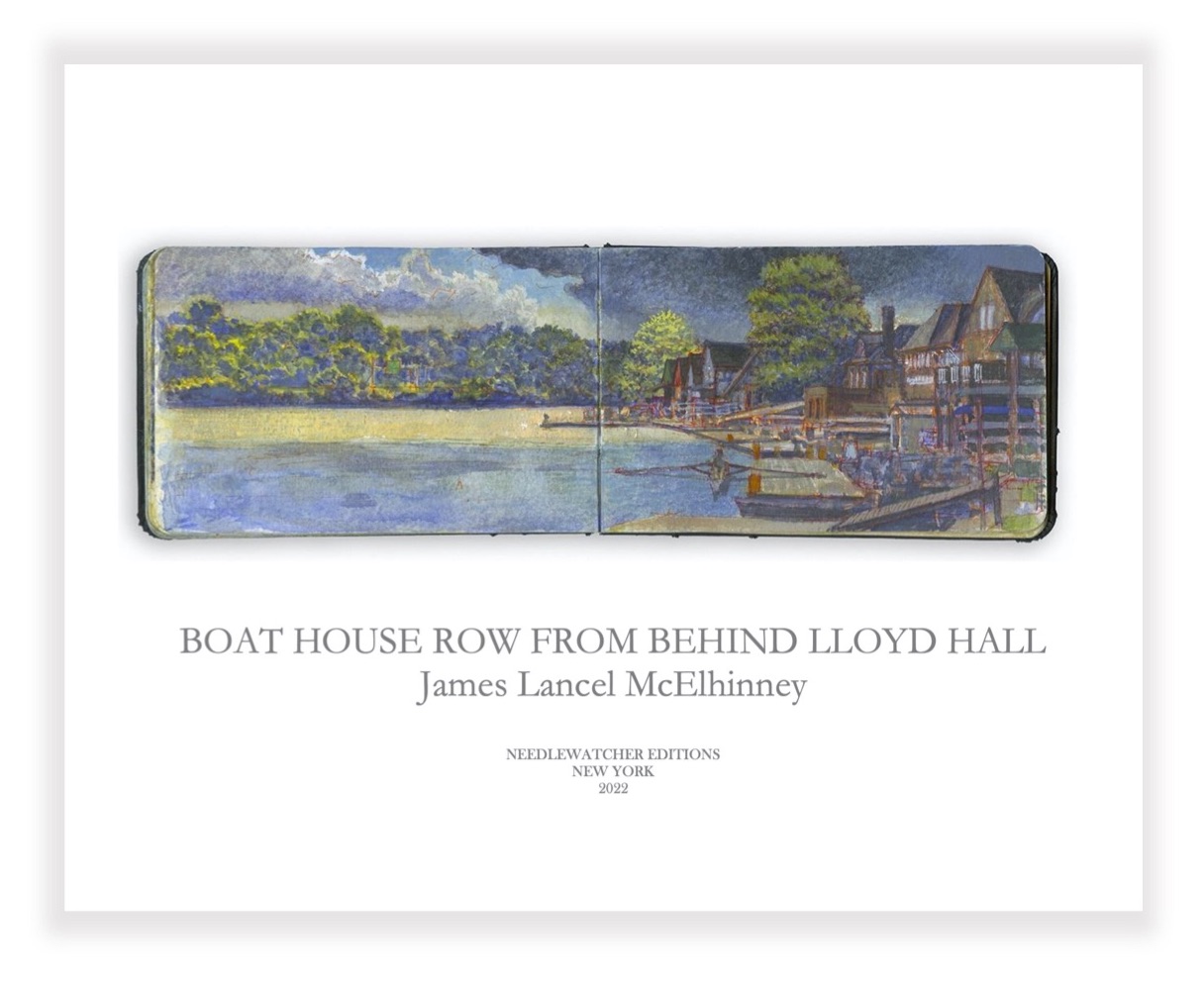

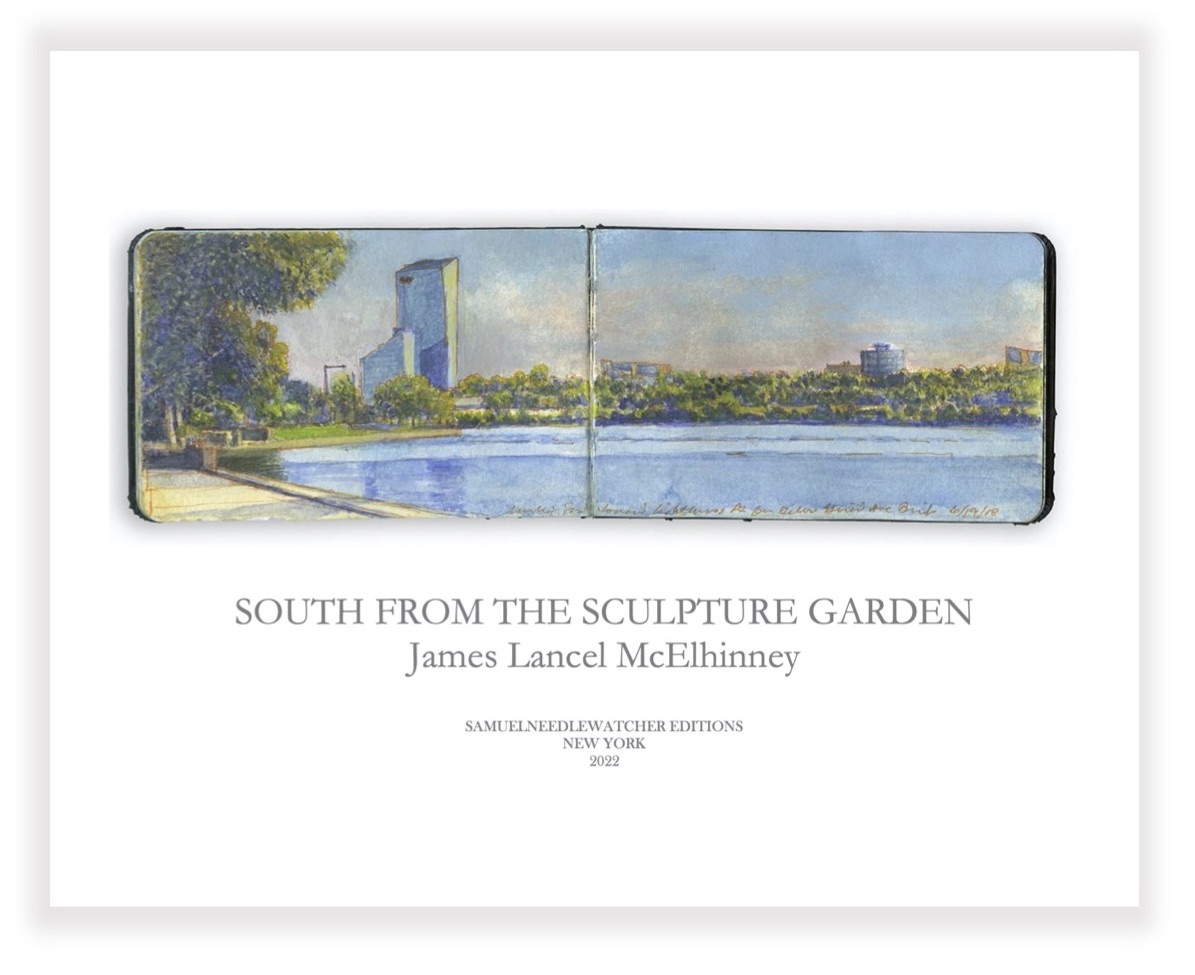

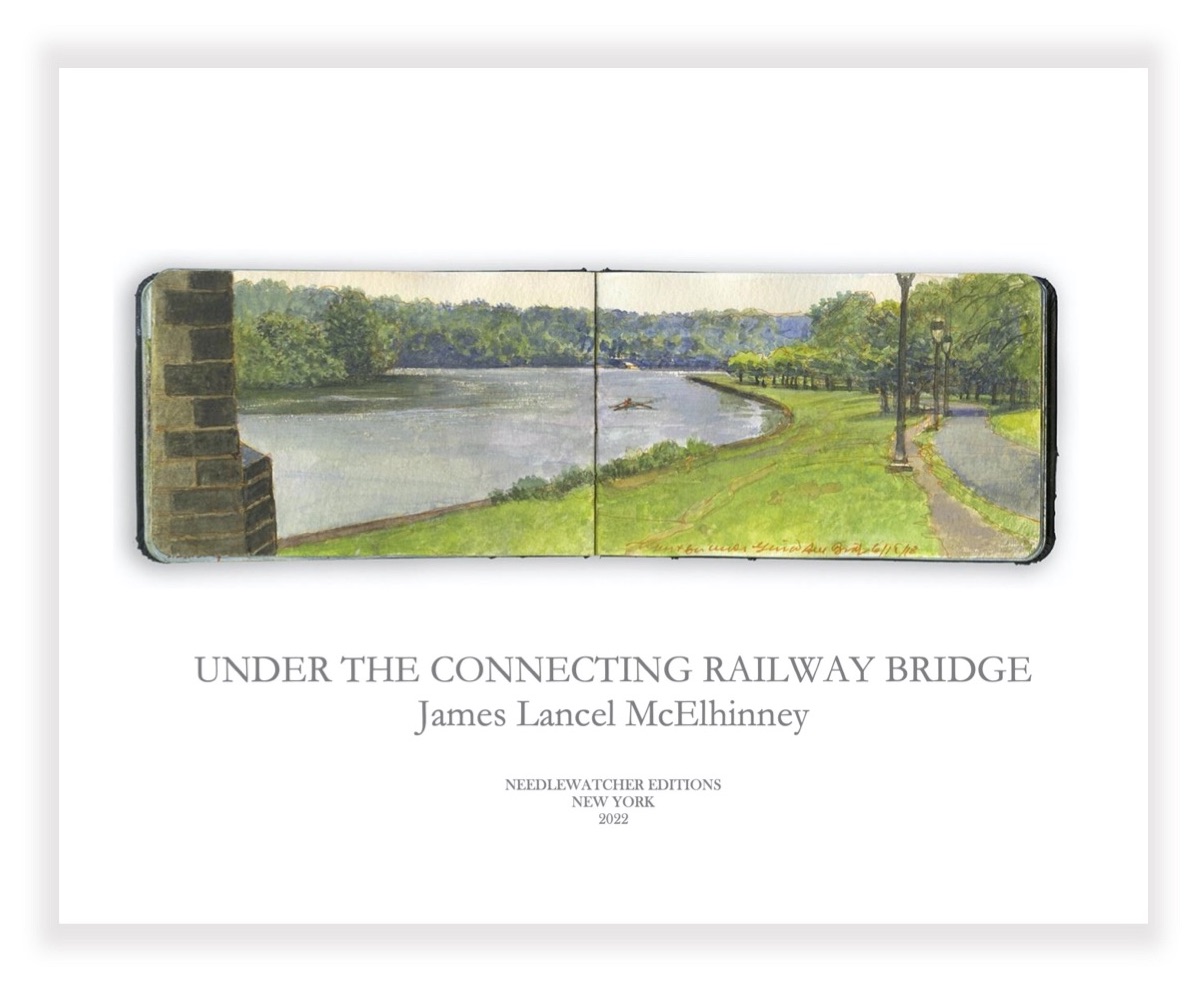

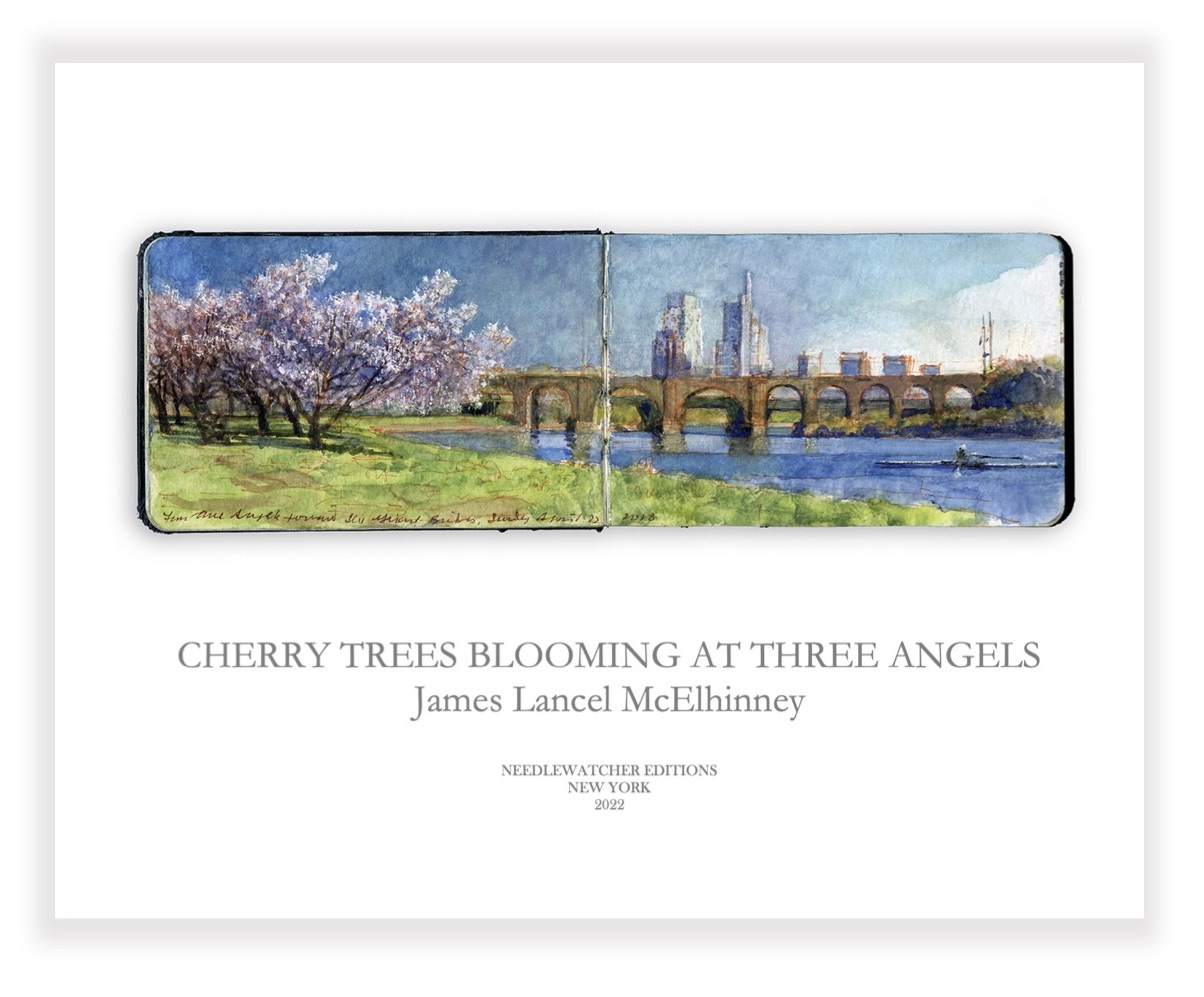

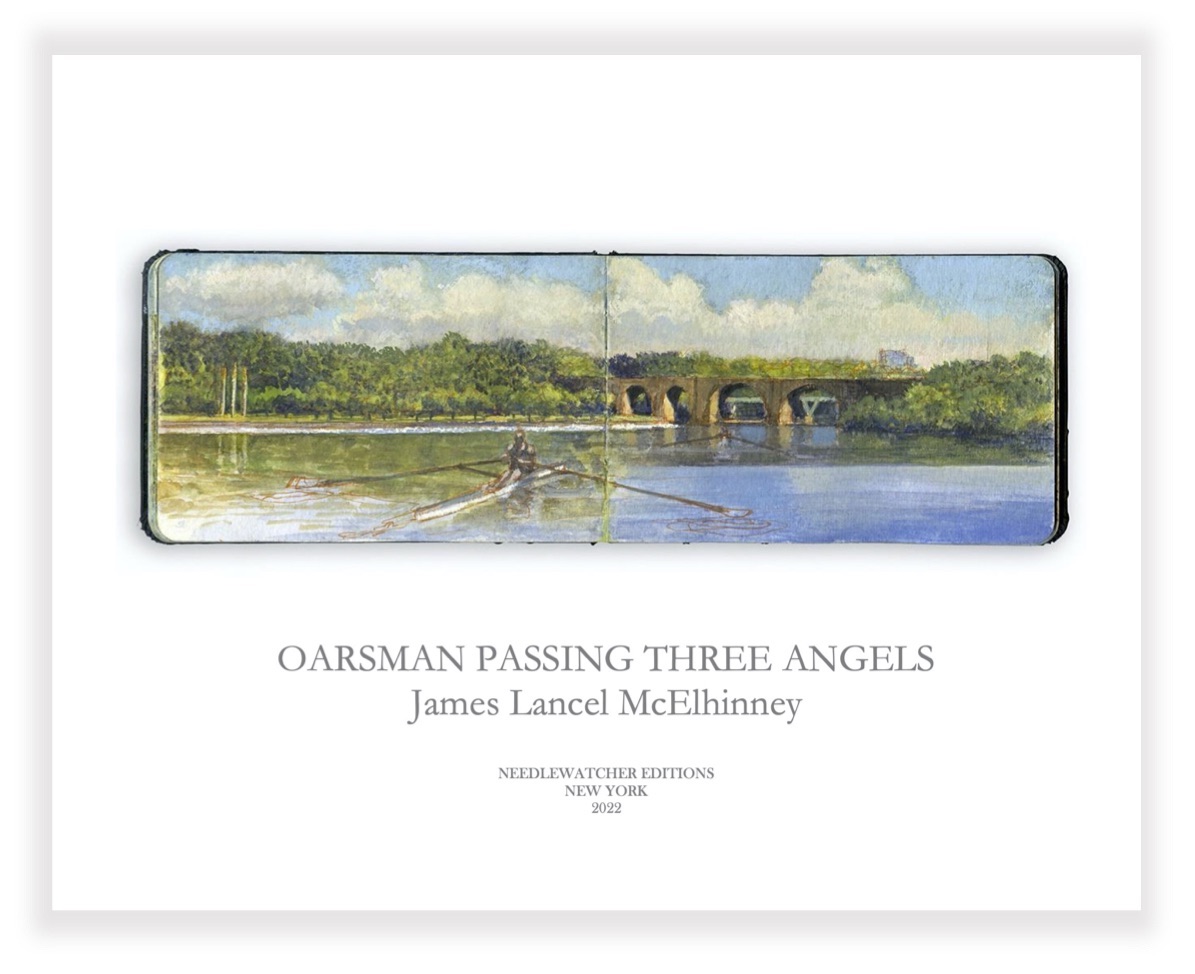

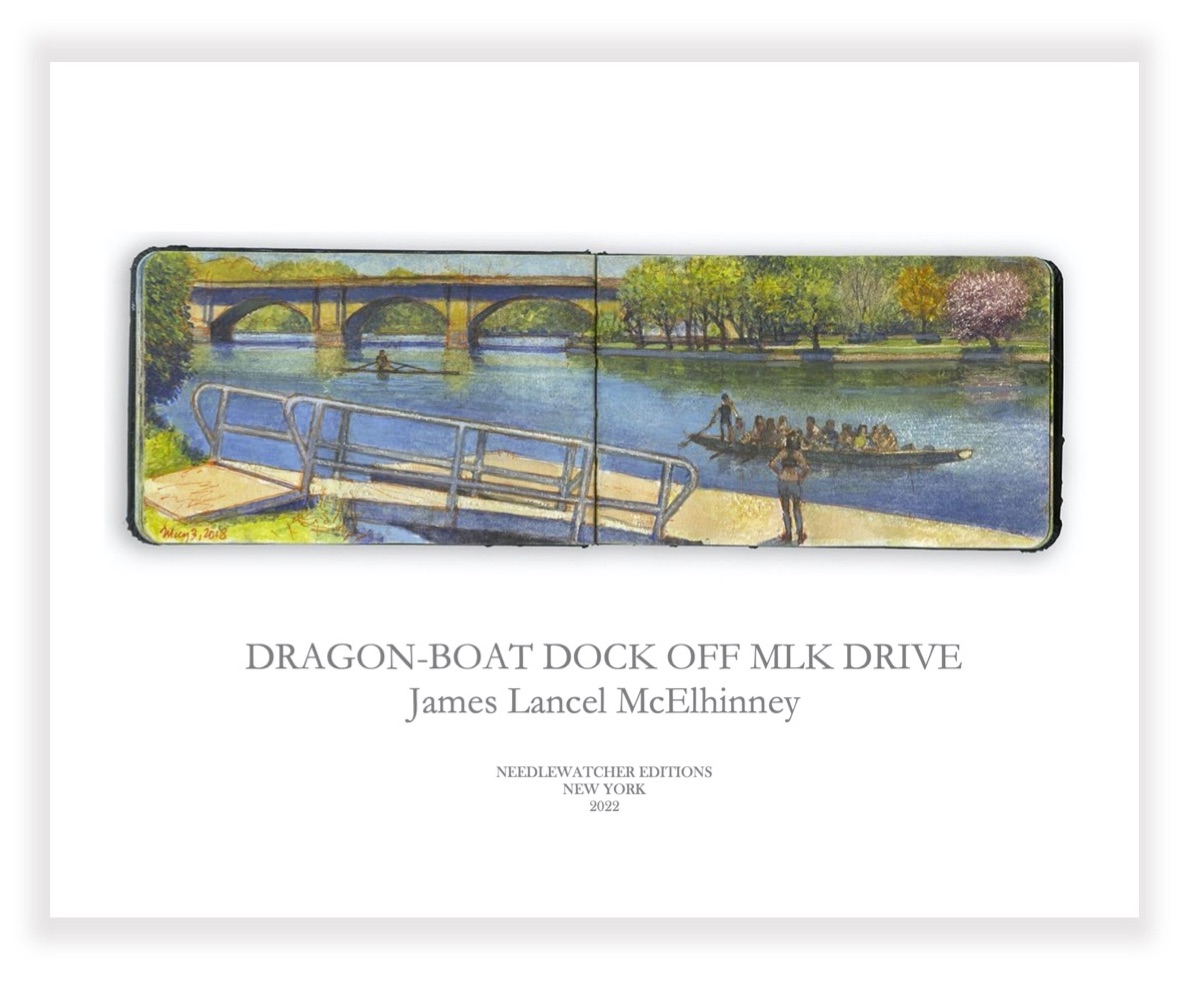

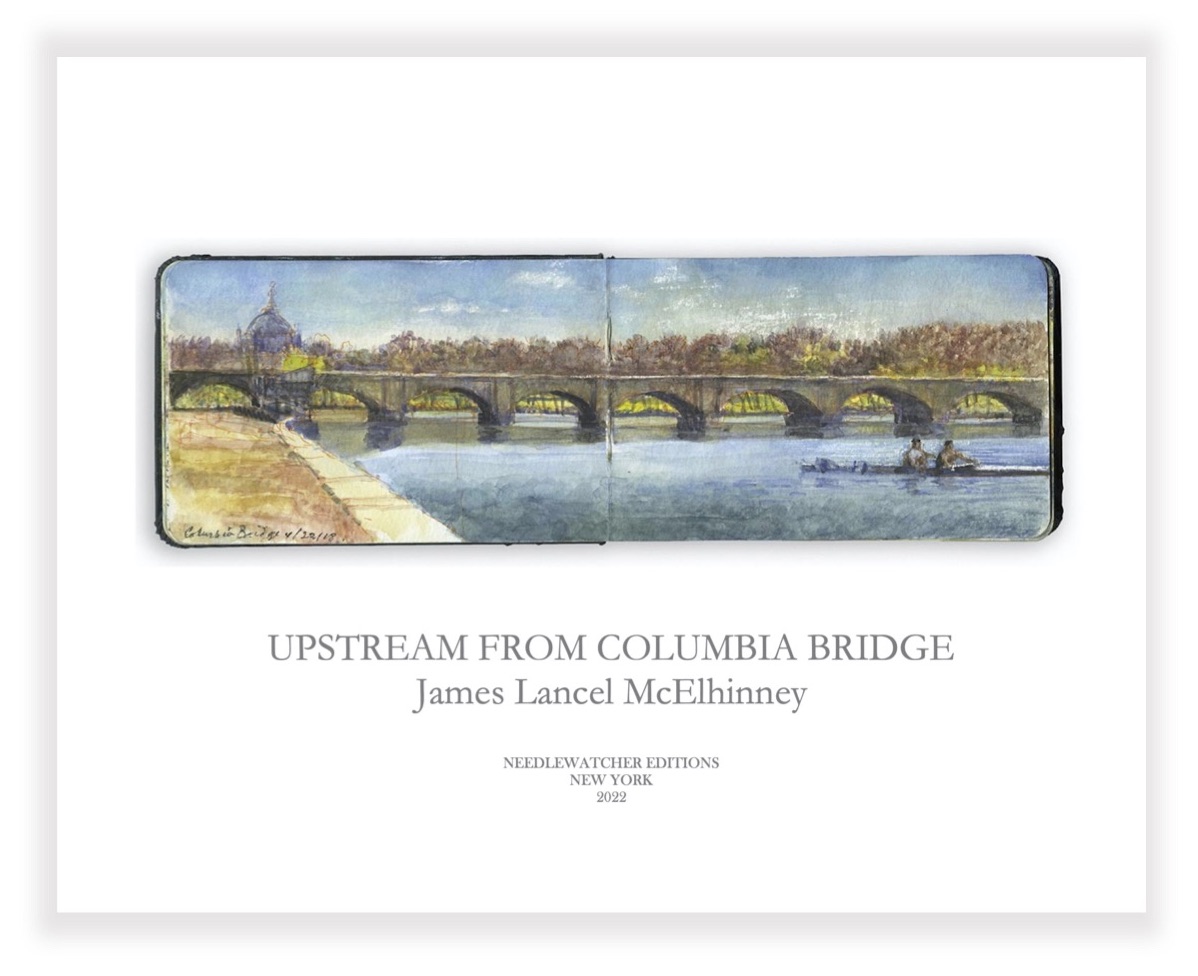

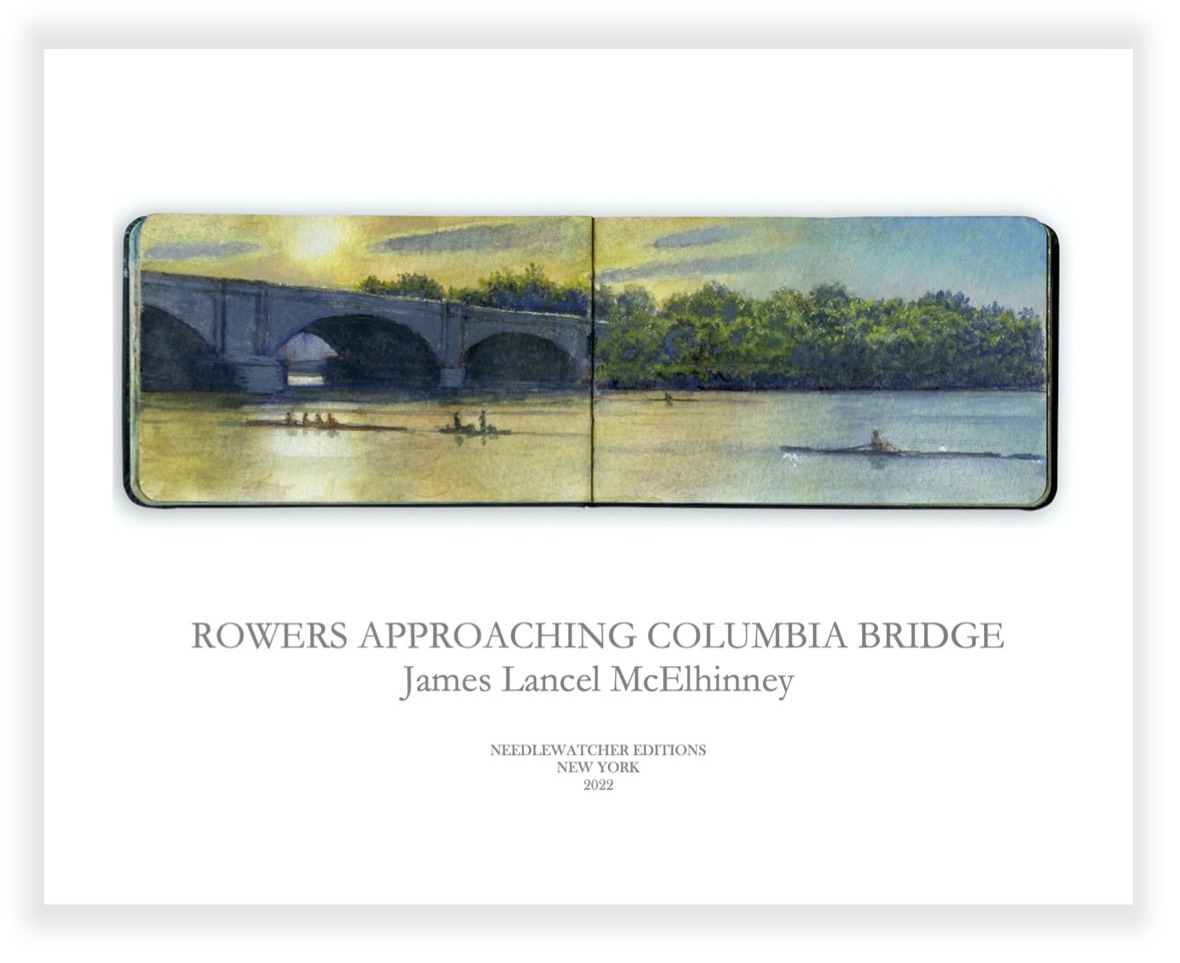

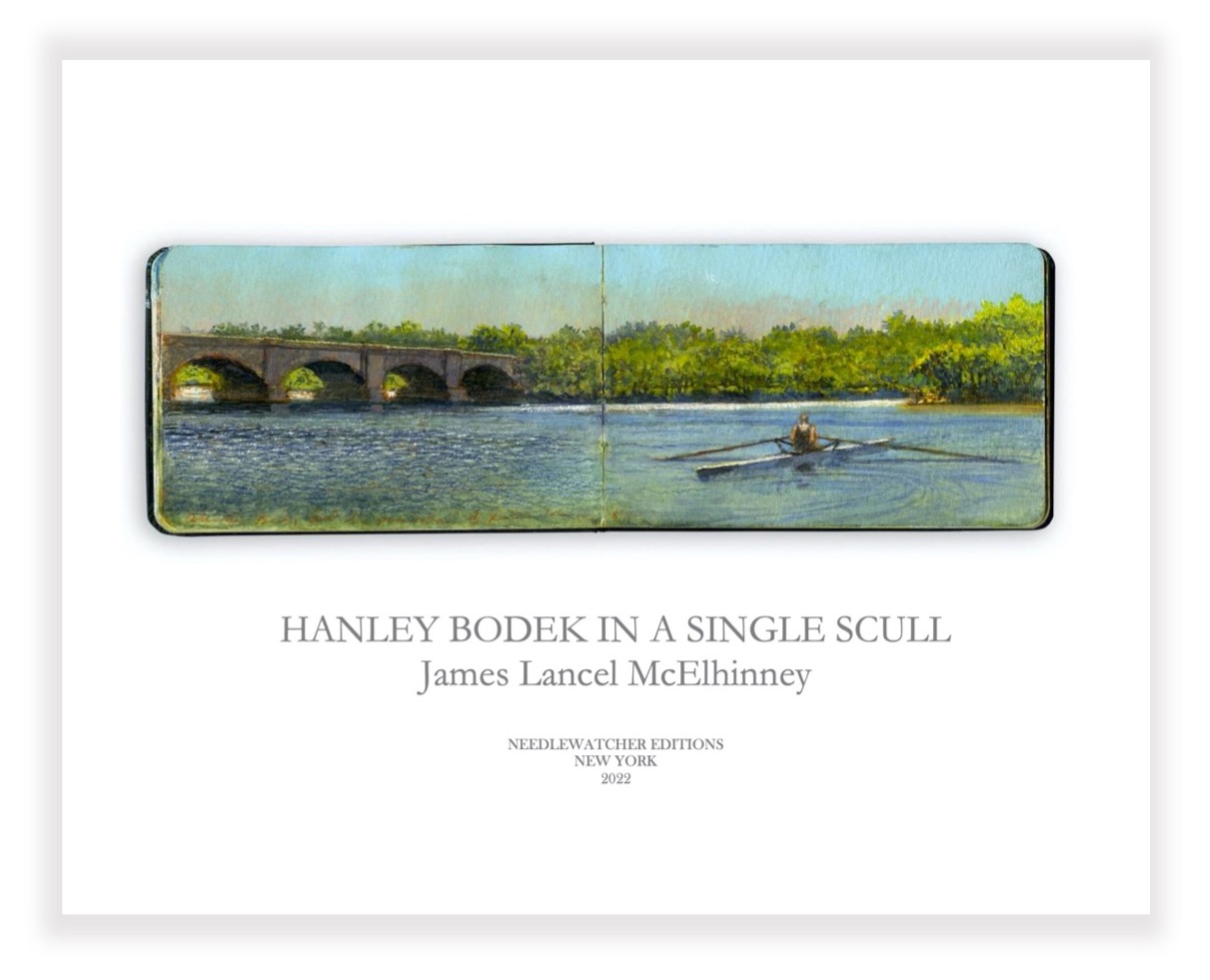

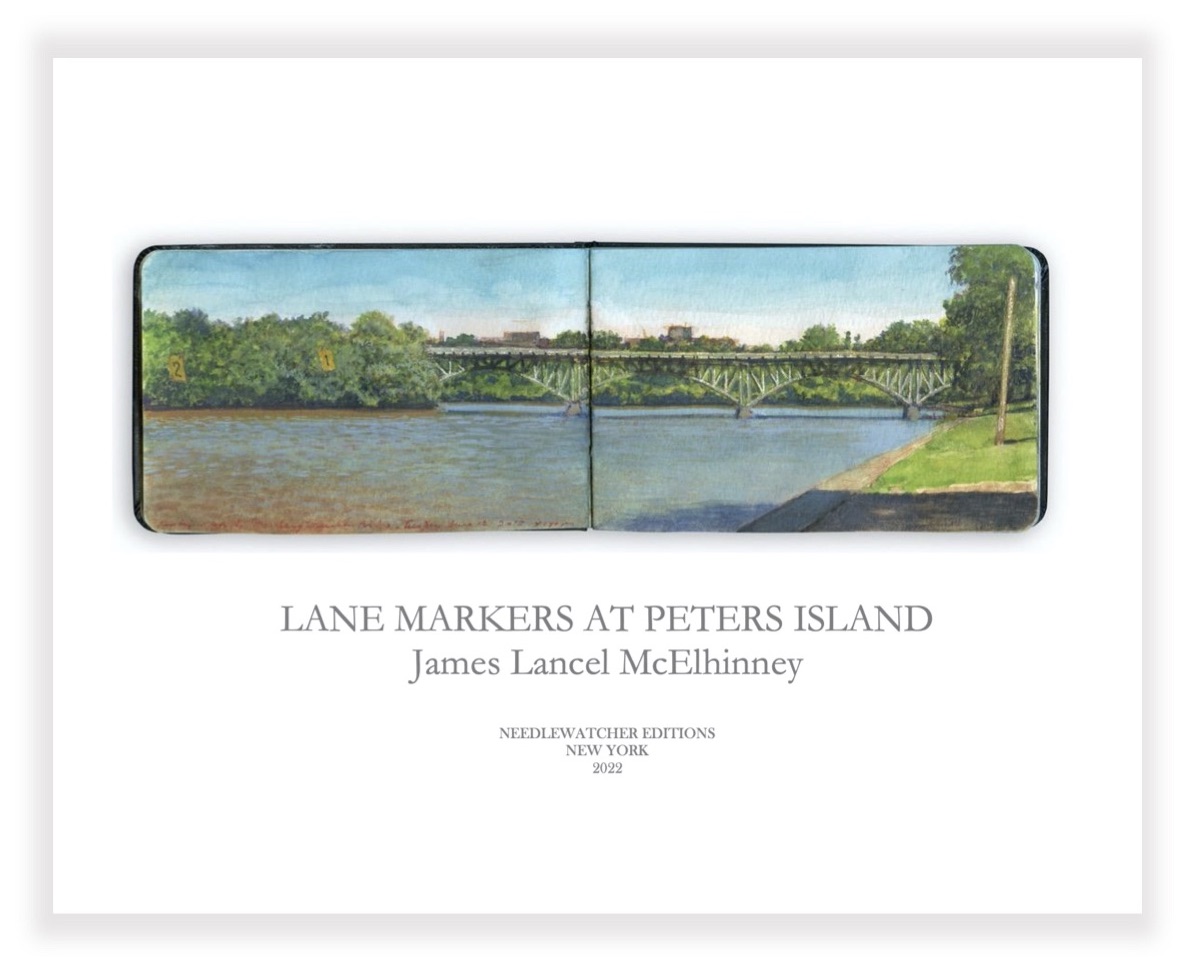

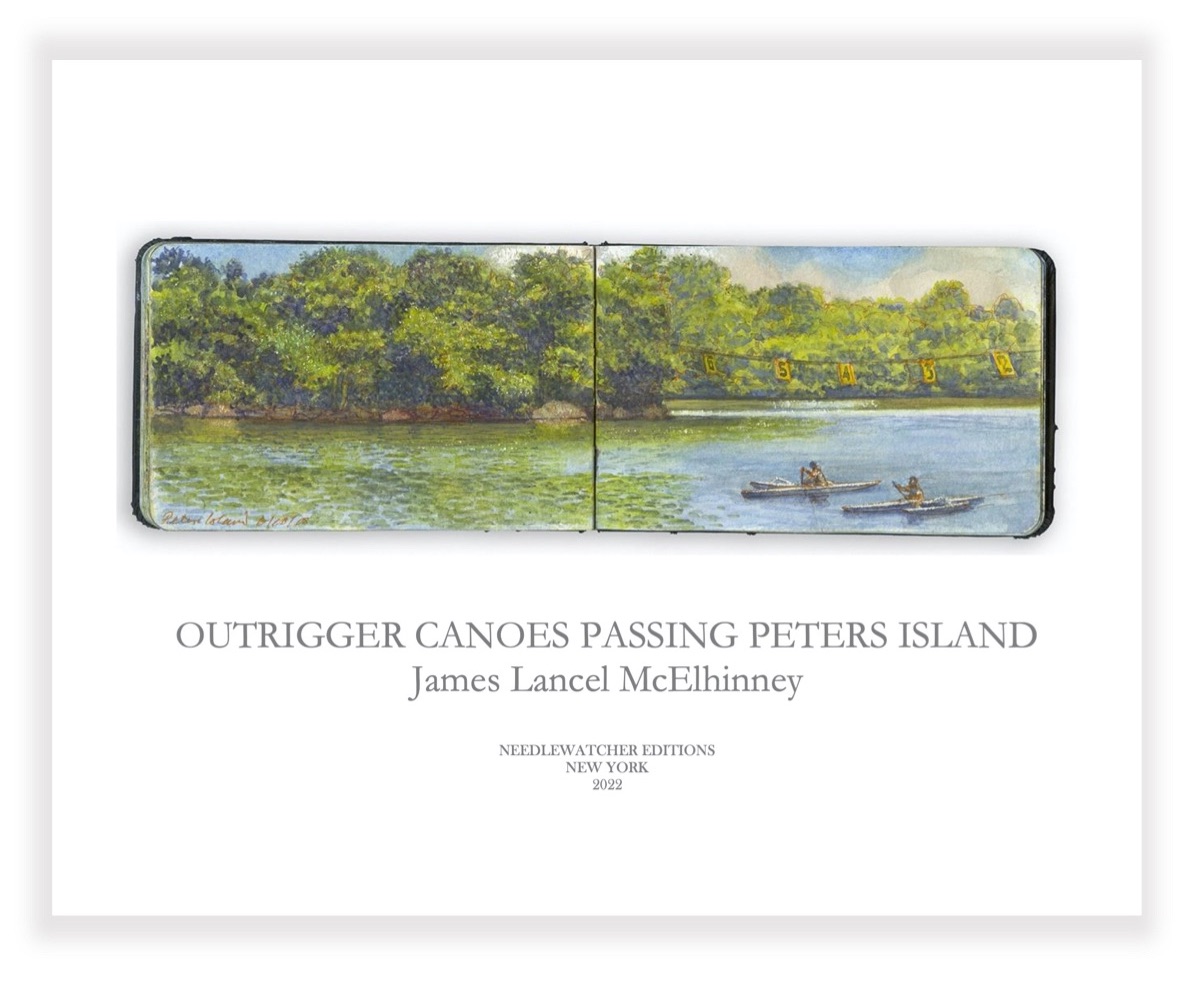

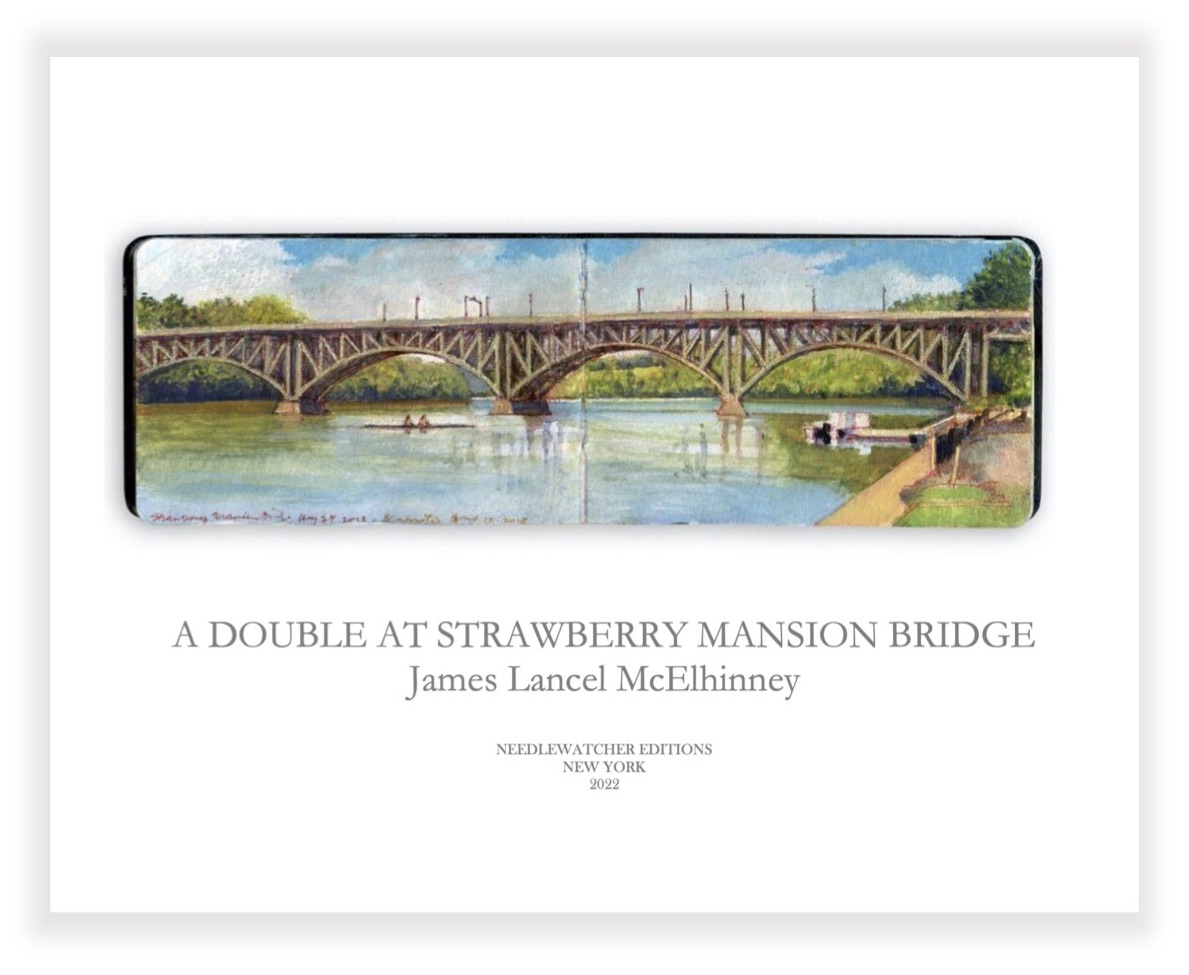

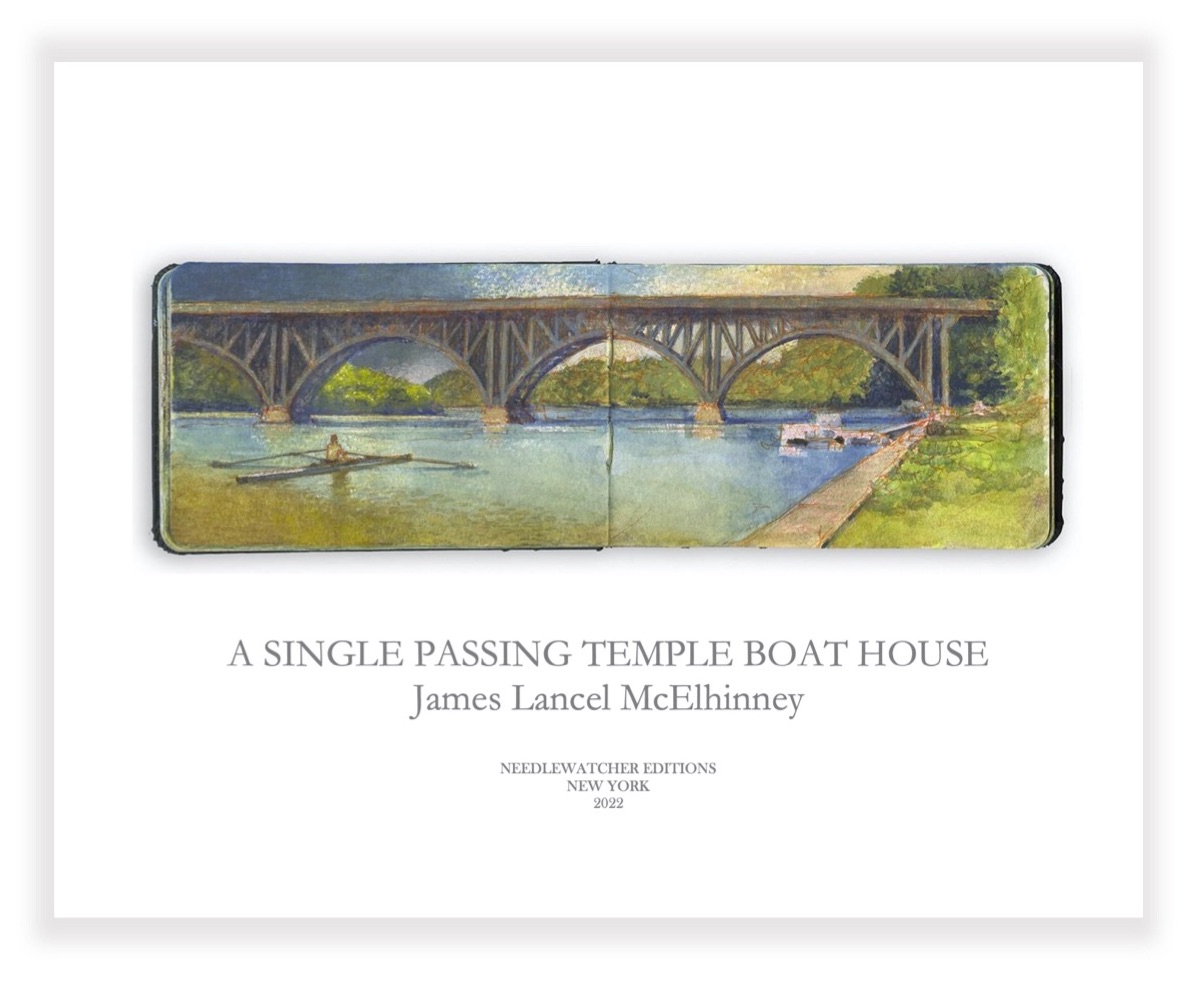

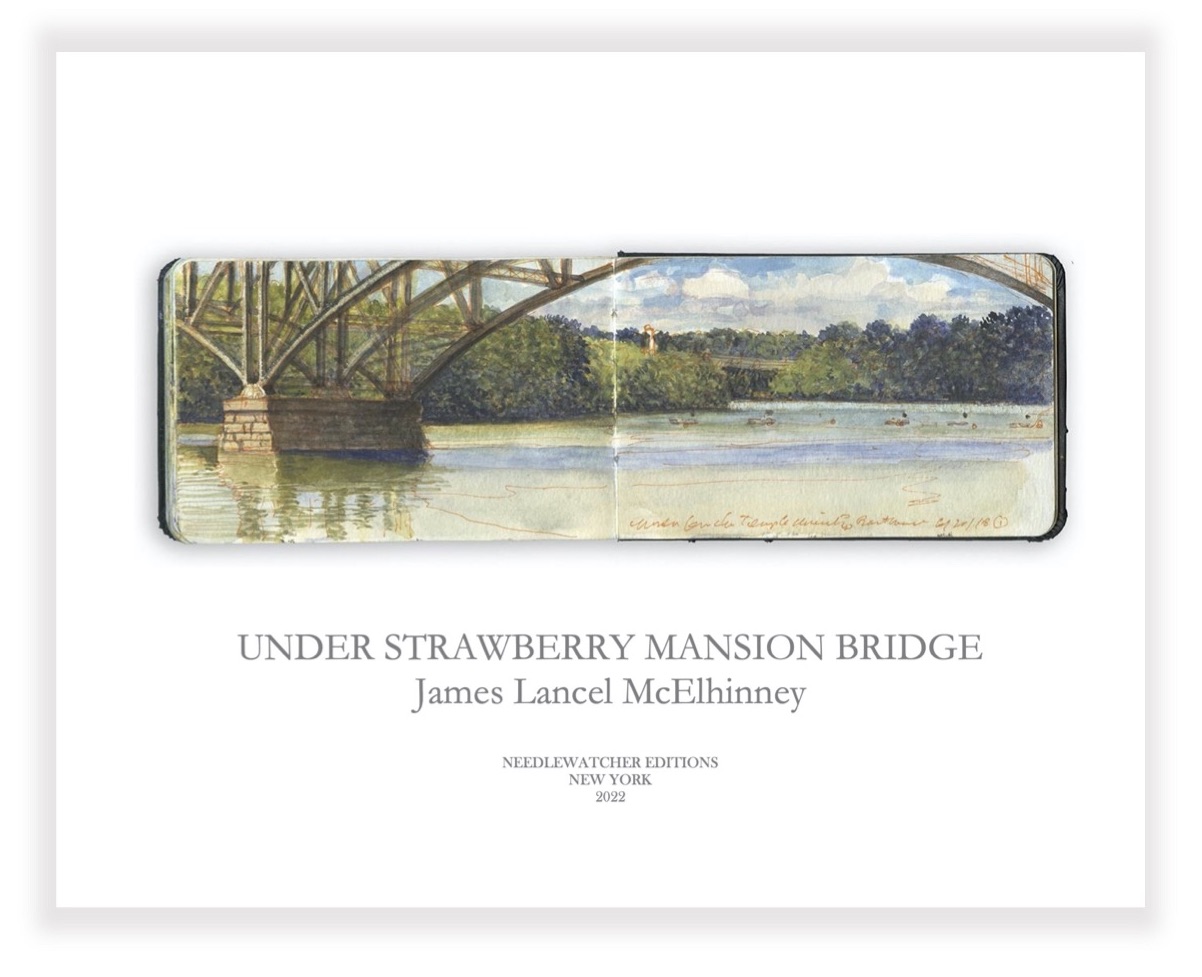

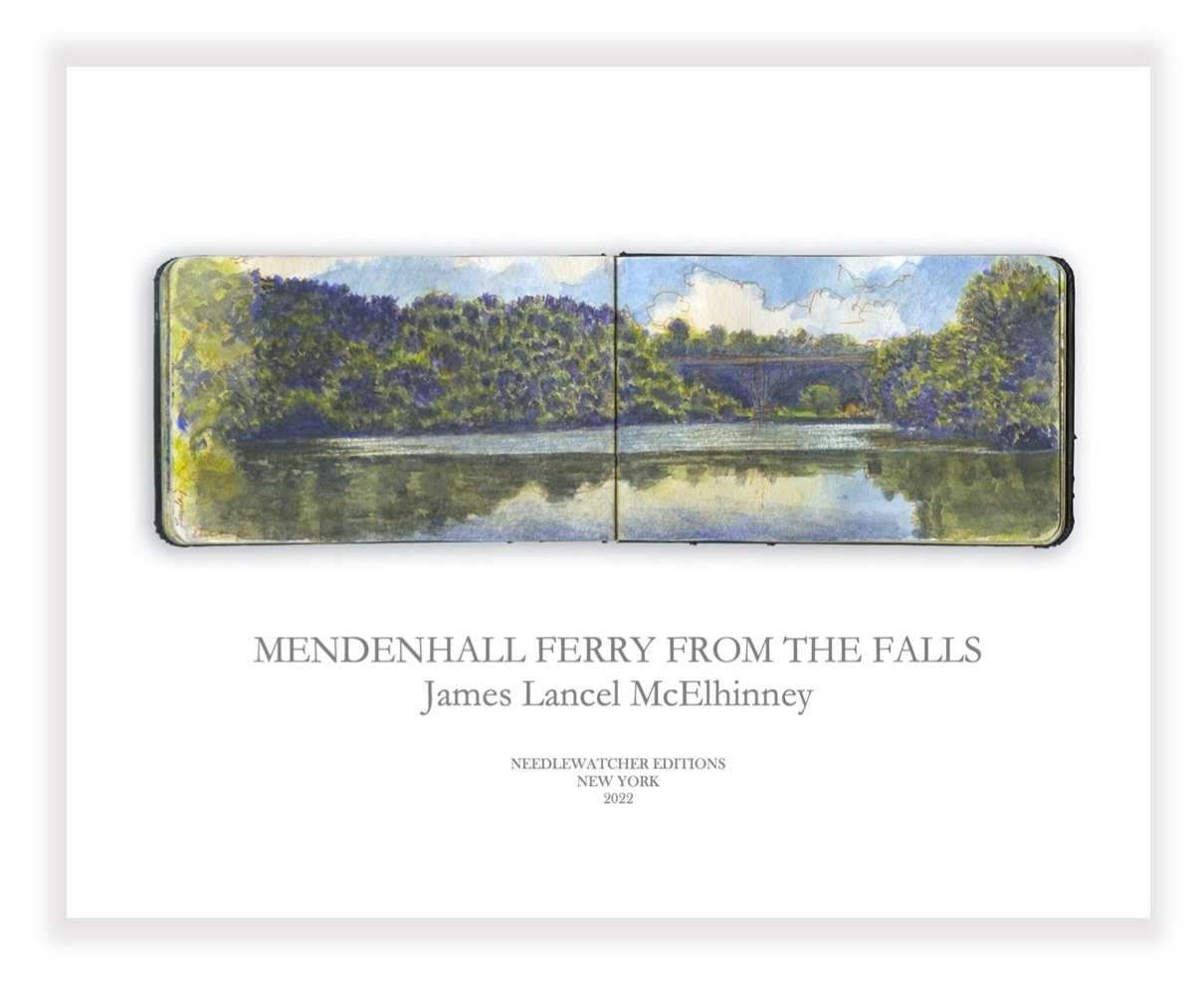

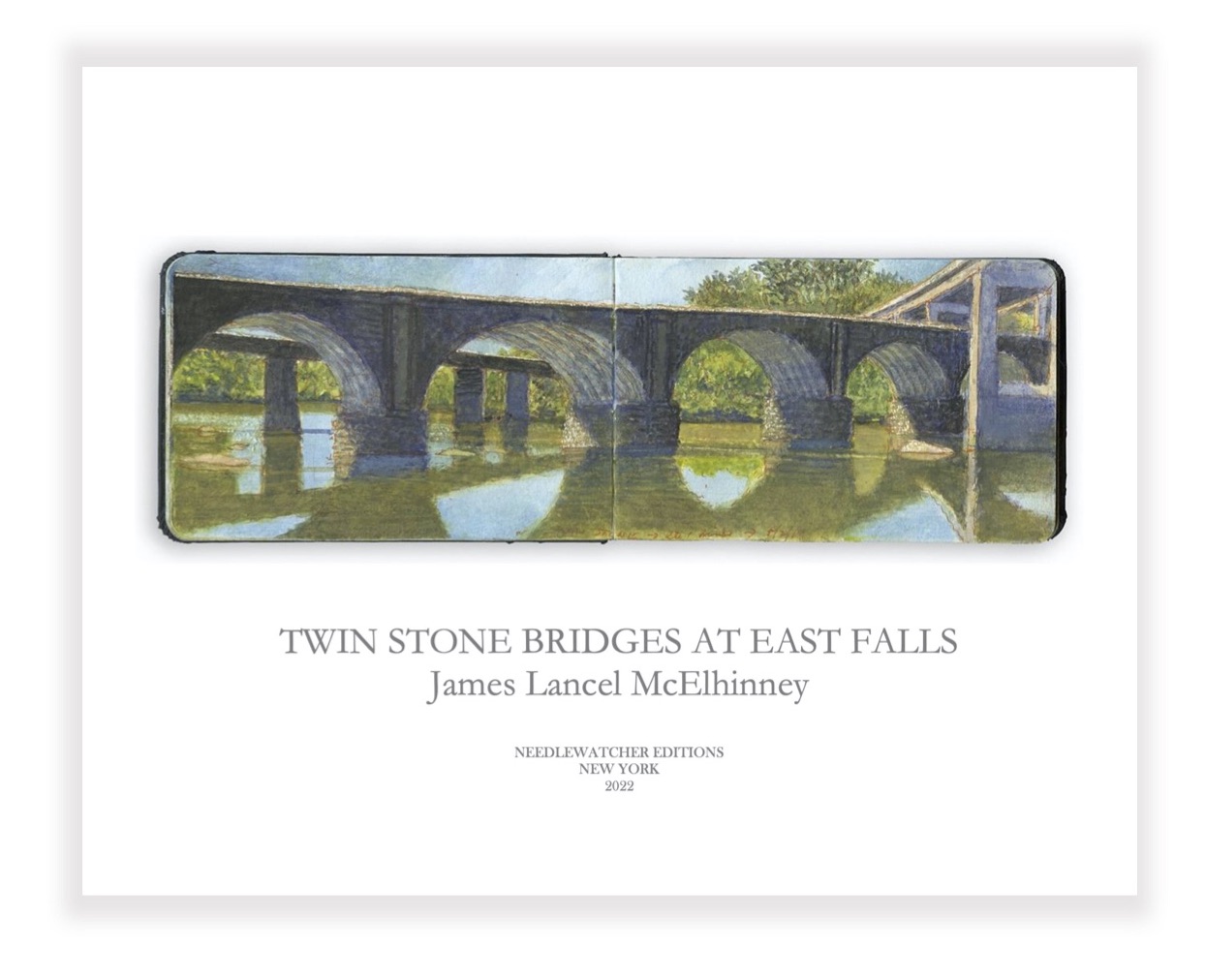

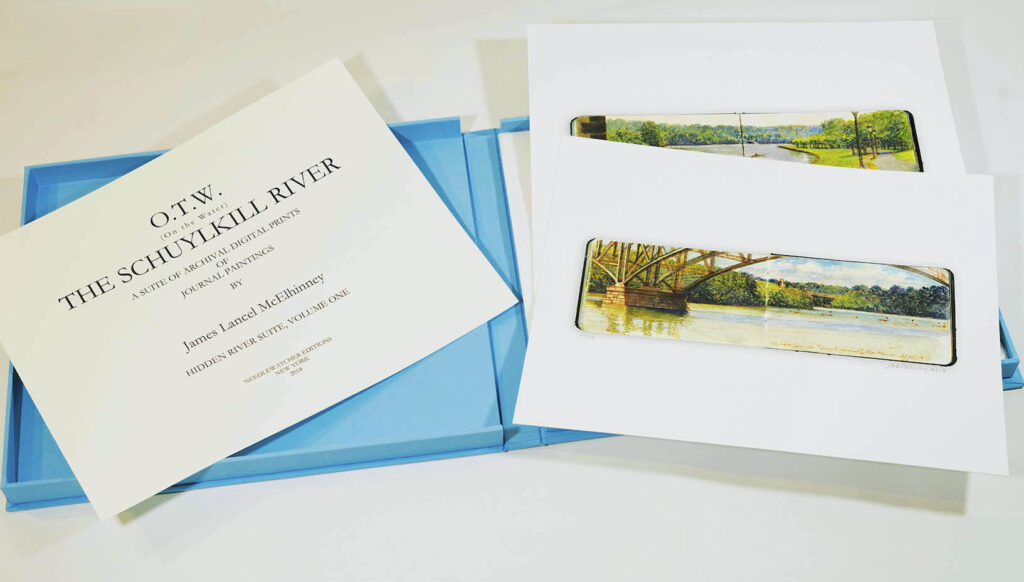

In 2017-18, I filled a painting-journal with sites along the river, from East Falls to Fairmount. These formed the centerpiece of an installation at Independence Seaport Museum at Philadelphia’s Penns’ Landing. Seven of those images were published as a fine press limited edition. Those views and and more are now being unpacked by Needlewatcher Editions as affordable individual archival pigment prints, in the spirit of expeditionary & Grand Tour loose-sheets and bookplates.

—J.L. McElhinney, 2022

These images are drawn from James Lancel McElhinney’s exploration of the Schuylkill River, from Fairmount to the Falls. The fine press limited-edition the centerpiece of the installation O.T.W. On the Water. The Schuylkill River, (below) at Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia. October 24, 2018- January 5, 2020.

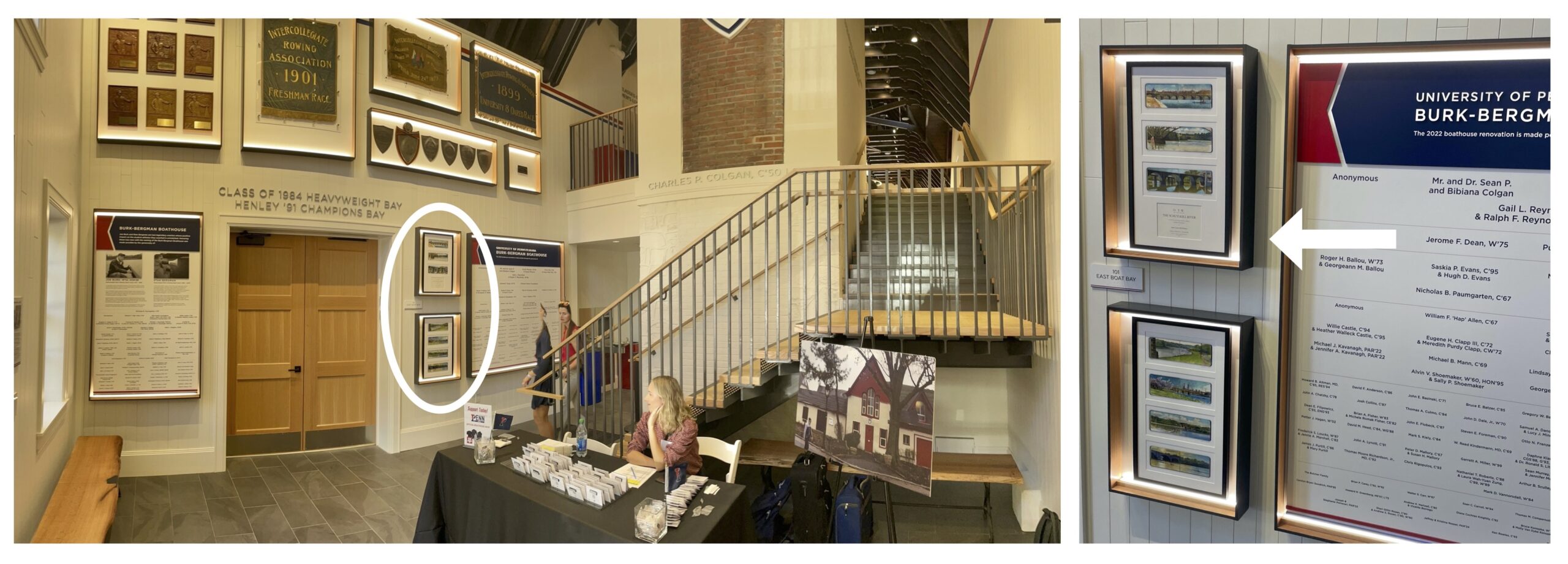

Prints from O.T.W. On the Water. The Schuylkill River have been installed in the lobby of the newly-renovated Burk-Bergman University of Pennsylvania Boat House, on Philadelphia’s historic Boat House Row (below)

Format: Each archival pigment print is on high-quality acid-free paper. Sheet size: 11 x 14 inches. Image size: 3.5 x 10.5 inches. Printed by Orion Studios in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Following the traditions of expeditionary art, a descriptive legend is printed below a full-size facsimile print of one of James Lancel McElhinney’s journal paintings; signed by hand below the lower right-hand corner.

(Scroll down)

OTW_1. Fairmount Waterworks and Philadelphia Art Museum.

OTW_1. Fairmount Waterworks and Philadelphia Art Museum.

OTW_2. Fairmount Dam from the Summit. $250.00 Purchase now

OTW_3. Boat House Row from behind Lloyd Hall. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.

OTW_3. Boat House Row from behind Lloyd Hall. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.

OTW_4. Looking south from the Ellen Philips Samuel Memorial Sculpture Garden.

OTW_5. North from under the Railway Connecting Bridge. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.

OTW_5. North from under the Railway Connecting Bridge. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.

OTW_6. Cherry Trees Blooming at Three Angels. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.:

OTW_6. Cherry Trees Blooming at Three Angels. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.:

OTW_7. Oarsman passing Three Angels. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.

OTW_7. Oarsman passing Three Angels. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.

OTW_8. Columbia Bridge and the Dragon-Boat Dock. Price:

OTW_8. Columbia Bridge and the Dragon-Boat Dock. Price:

OTW_9. Columbia Double with Memorial Hall. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.

OTW_10. Rowers approaching Columbia Bridge. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.Price:

OTW_10. Rowers approaching Columbia Bridge. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.Price:

OTW_11. Single. Columbia Bridge. Peters Island.

OTW_11. Single. Columbia Bridge. Peters Island.

OTW_12. Lane Markers at Peters Island. Price:

OTW_12. Lane Markers at Peters Island. Price:

OTW_14. Outrigger Canoes Passing Peters Island.

OTW_14. Outrigger Canoes Passing Peters Island.

OTW_15. Strawberry Mansion Bridge from Temple Boathouse.

OTW_15. Strawberry Mansion Bridge from Temple Boathouse.

OTW_16. Single Scull Passing Strawberry Mansion Bridge.

OTW_16. Single Scull Passing Strawberry Mansion Bridge.

OTW_17. Under Strawberry Mansion Bridge. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.

OTW_17. Under Strawberry Mansion Bridge. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.

OTW_18. Mendenhall Ferry. Below the Falls.

OTW_18. Mendenhall Ferry. Below the Falls.

OTW_19. Twin Stone Bridges. East Falls. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.

OTW_19. Twin Stone Bridges. East Falls. Included in the limited edition O.T.W. The Schuylkill River.

PURCHASING OPTIONS (Click on the image below)

Limited copies of O.T.W. The Schuylkill River are still available: Click on the image below for more details about the fine press limited edition of 50 copies released in 2018.

Return to BOOKSTORE

American landscape painting was born not on the easel of Thomas Cole, but in the sketchbooks of British military officers like Thomas Davies and Governor Pownall during the French and Indian War. Elaborated by professional artists such as Paul Sandby, these North America vistas published in London as Scenographia Americana motivated a new generation of artists such as William and Thomas Birch, Joshua Shaw, William Guy Wall and Samuel Seymour to expand the Grand Tour aesthetic to the New World, again in the form of prints created for popular consumption. J.M.W. Turner cut his teeth translating topographical drawings of the Second Anglo-Mysore War for a booming art-publishing industry. Albert Bierstadt, F.E. Church and Thomas Moran all translated their grand visions of South America and the Rocky Mountain West into chromolithographs and etchings. In 1872 and 1874, Appleton & Company released William Cullen Bryant’s Picturesque America; a compendium of scenic destinations across the United States. Its publication coincided with the rise of a tourism industry that delivered visitors to natural wonders that a nascent environmental movement hastened to protect.

A new set of prints is now being developed, built on this tradition. Drawn from my painting-journals, like the Sketchbook Traveler books produced by Schiffer Publishing, these individual prints celebrate personal travel with an environmentally mindful expeditionary spirit.

(Click on any of the images above to learn more)

(Preliminary comments I delivered at Art Talk/The Artist’s Estate; a panel discussion held in conjunction with the exhibition Known/Unknown: Artists’ Estates, at Blue Hill Center for the Arts in Pearl River, New York. November 12, 2022.)

“It’s great to be here. I would like to extend my hearty thanks to Blue Hill Art & Cultural Center, the Marjorie Strider Foundation, and Barbara Sussman of Fog Hill & Company, for giving me an opportunity to address you all today. I’ll try to keep my comments brief.

Let me begin by telling you a story, Exploring a wooded island-chain in the vast waters of Secaucus Bay, hundreds of years in the future, a team of archaeologists makes a startling discovery. Boring down into sylvan prominences that once were landfills, excavators bring up cylindrical soil samples. Something captures their attention. At a level corresponding to the second quarter of the 21st century, they notice an anomalous, brightly-colored band—the residue of countless works of art. Other digs yielded similar findings.

A plastic Ziplock bag is retrieved from a former dumpsite near the ruins of Santa Fe. Contained within is a cassette-tape of Terry Allen’s 1979 album Lubbock on Everything. One track holds particular interest. Truckload of Art recalls a highway fatality, when blue-chip artworks worth millions of dollars were consumed in the fiery wreck of a westbound Cab-over Peterbilt 18-wheeler, somewhere in Flyover Country.

Could it be a clue? Why was so much artwork abandoned during such a brief period of time? What could explain this massive surplus? Archaeologists compared their colorful cake-layer to strata from volcanic cataclysms, or fallout from the asteroid-strike that wiped out the dinosaurs. Farmers were known to have plowed under crops in exchange for government subsidies, but what calamity had compelled society to shed so quickly such massive quantities of artwork? Lacking sufficient primary documents to support or refute any of the theories pout forward, the search for clues continues. . .

Before anything like this comes to pass, mankind could be annihilated by a nuclear holocaust or killer plagues. Or—just maybe—artists might wake up to the fact that none of them will live forever, and take steps to preserve their legacies.

In all likelihood, a majority of makers will leave their heirs with a chaotic assortment of objects and papers, with no plan of action for its management. Restrained by sentiment, grief, and vain hope of future sales, the inheritors warehouse these heirlooms at great cost. Decades pass. Nothing happens. Bleeding money, the heirs make the painful decision to get rid of it. Sometime later, one of the paintings comes to light at a flea-market, hanging on a snow-fence. Another sells for peanuts at a rural auction. “Listed Artist” is lettered in pencil, on a paper tag dangling from a loop of thread, taped to a battered frame. The artist’s name rings a bell, but nobody remembers why.

We (Boomer artists) are sailing into a perfect storm. A sea-change is underway in how artworks are produced and consumed. When Tom Wolfe published “The Painted Word” in 1975, he predicted dire consequences, as a result of art-schools and universities flooding the gallery scene with legions of graduates wielding “artist’s statements.” Some of his predictions have come true, but he missed the mark when it came to foregrounding the backstory. Artworks may speak for themselves, but only to those who know how to listen.

While art fairs, auction houses, online sales platforms and social media now provide makers and dealers with many ways to sell art, new hires in studio art at art schools and colleges are in decline. As boomer art professors retire, their job lines disappear. Whole departments are being allowed to vanish through attrition. For the sake of brevity, let’s look at how this small corner of the market is being affected by these trends.

Studio art professors regard themselves as professional artists. The blue-chip art business sees them quite differently, despite the fact that many have been producing and exhibiting artworks for decades. Let’s say that a teaching artist shows twenty works at a gallery. Only ten manage to sell. The remainder are returned to the artist, who squirrels them away; saving them for future buyers, or a pipe-dream retrospective. The problem with this line of reasoning is that it defies real market practices. For example. One consigns an object to be sold at auction. If bidding fails to reach the “reserve”, it is “bought in.” Having been exposed to the market, as an unsold lot it would be considered “burned,” unsaleable for at least a few years, when it might be offered again–in a different market setting, perhaps at a lower price. Publishers release hardcover editions. Some become bestsellers. Others that die on the shelf are remaindered, to be sold at cut-rate prices.

Having taught in higher education for decades, I have come to understand why teaching artists are benighted to these facts of life. They consider themselves exempt. It’s too easy to conflate the meritocracy of academe with market validation, despite the fact that one has nothing to do with the other. A solo show at a gallery could be the equivalent to publishing an essay in a peer-reviewed journal, and thus count toward meeting expectations at one’s day job, and advance their progress toward tenure and promotion. Sales are not part of that calculus. Showing is enough.

But what of those works that came back from these exhibitions? Having been exposed to the market and refused a sale, why are they exempt from the taint of failure—like auction-house “buy-ins,” or remaindered books? The answer is simple. They were made not to be consumed by the market, but to generate academic capital. In other words, most teaching artists are not subject to the rules of the game because they are not on the field. They’re not even in the locker room. Despite this fact, a large number of studio artists working in academe continue to believe that they are shaping culture in durable ways. One supposes they are—by way of the “Butterfly Effect.” What most will accomplish is to be blessed with a creative lifestyle; no small achievement in itself. Unless steps are taken by these folks to establish some kind of durable public legacy; as part of their creative practice, all will be forgotten. It’s one thing to be recognized by one’s peers in one’s lifetime. It’s quite another matter to be remembered by posterity. If the future cannot find you, you were never here.

Let’s do a little math. A painting professor might have had solo exhibitions every two years. Each show featured twenty works, half of which sold. The other half went into storage. Retiring after a forty-year career, the professor find herself/himself burdened with the care and feeding of hundreds of artworks for which no market exists. What can be done? Of course, there will always be dauntless souls who churn out new works until they drop, leaving to their inheritors a chaotic assortment of equipment, papers, sketches, paintings, drawings, and maquettes. Loath to consign all this treasure to dumpsters and landfills, Heirs are often clueless about how to manage it all. What are their options? How might they proceed? Finding answers to those questions is why we are gathered here today.”

(To be continued)