Thomas Pownall, Paul Sandby and William Elliott. View of the Great Cohoes Falls on the Mohawk River. 1760. Bookplate engraving after the original print. Collection of the Albany Institute of History and Art.

Topographical landscape painting was already an established genre that dovetailed naturally with the art of map-making and scientific illustration. Specializing in watercolor with a background in mapmaking, Paul Sandby (1731–1809) gained acclaim as a landscape painter. He was the ideal candidate to oversee the drawing program at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, where it was believed that by learning how to make art, military officers would become keener observers. Sandby began teaching at Woolwich in 1768. Scenographia Americana was published that year in a series of twenty-eight prints of North American landscapes drawn from observation by British military officers, including former Massachusetts governor Thomas Pownall. A view of the Great Falls at Cohoes on the Mohawk River was based on a drawing by Pownall, elaborated by Sandby in 1760 for the engraver William Elliott (1727-1766). An accomplished draughtsman, Pownall also served as Royal Governor of South Carolina, and as Lieutenant-Governor of New Jersey.

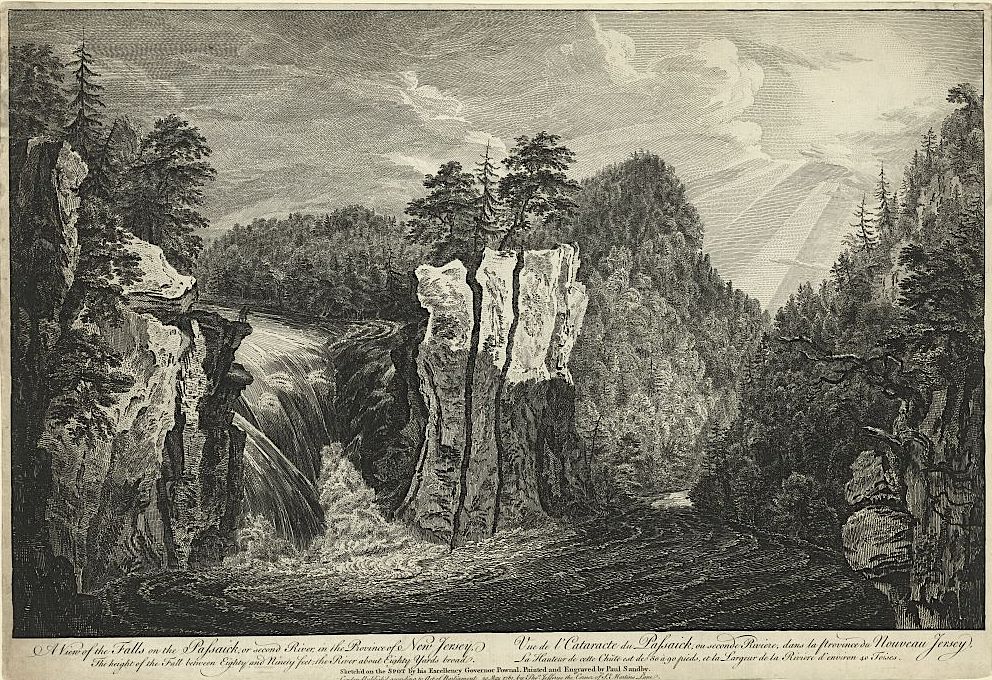

Pownall & Sandby. A View of the Falls of the Passaic River in New Jersey. Scenographia Americana.1768

Pownall & Sandby. A View of the Falls of the Passaic River in New Jersey. Scenographia Americana.1768

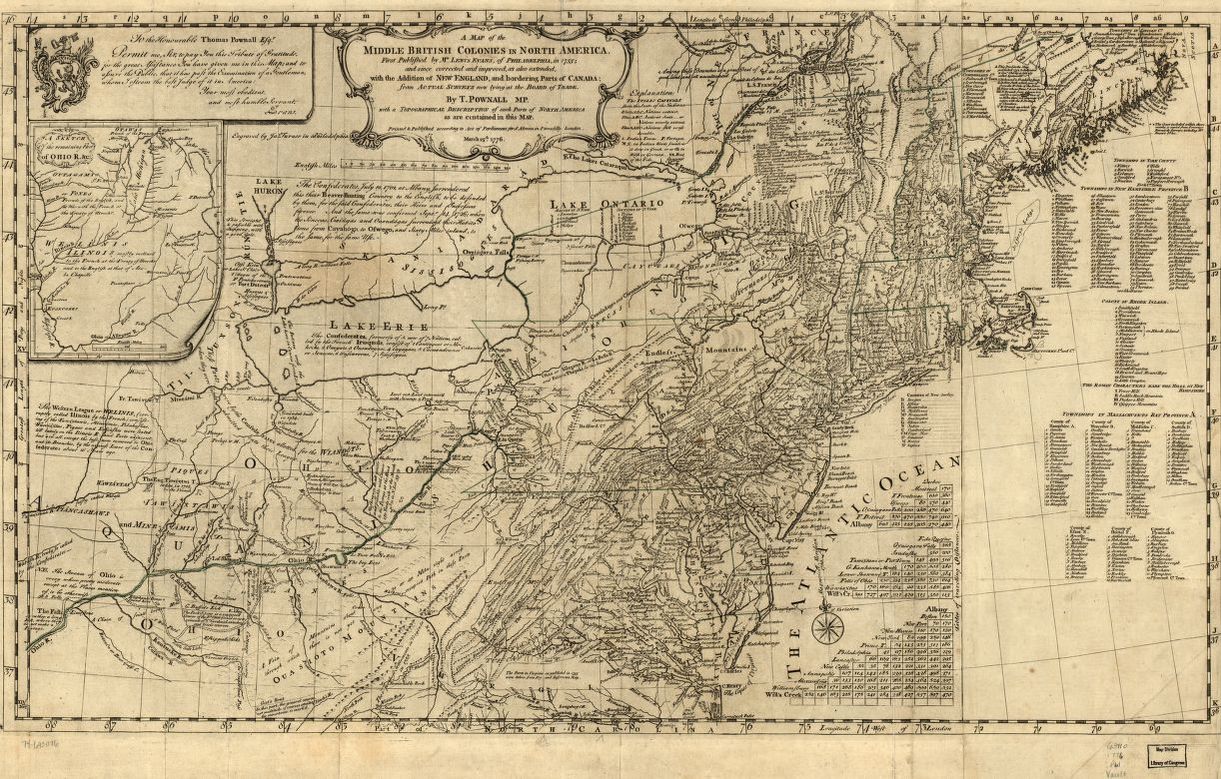

Engravings of views drawn by Pownall and other British military officers were published in London in 1768 as Scenographia Americana, six years before the first plates of Claude Lorrain’s Liber Veritatis (Book of Truth) were published by John Boydell, as mezzotint engravings by Richard Earlom. Pownall traveled extensively throughout British North America, making drawings, keeping a journal and later collaborating with cartographer Lewis Evans to produce the book, A Topographical Description of Such Parts of North America as are Contained in the Map of the Middle British Colonies, &c. in North America. Published at London by John Almon in 1776.

Lewis Evans. Map of the Middle British Colonies in North America. 1755-1776

“When I was afterward in a Situation to direct the Inquiries of others, I formed a set of instructions for directing the Observations and Remarks of such as were sent out to reconnoitre; and the Returns I received gave very sufficient information as far as it could go. If the Plan, which I proposed and began, has been observed through the (French and Indian) War, namely that of obliging every Scout to keep a Journal with Topographical Remarks; and upon the Returns of these, of copying into a Book (under a general Head, each within their respective District) all these Informations so returned; a very ample store of Topographical Knowledge of the country might have been collected and classed, which is now dispersed and lost. I can speak from experience of the Use of this; I experienced it is my own Province; such classed and posted Accounts would have proved a good Check of the Unfaithfulness of many an artificial journal cooked up by Scouting Parties; moreover the Habit of keeping such Journals, and making such Remarks, would have trained many a good Regimental Officer to become a real General. Without this Knowledge and practical Readiness in applying it, no Officer ought to be trusted with the command of a Body of Men.”

–Thomas Pownall

Paul Sandby is considered the father of watercolor landscape painting. In 1768 Sandby accepted a position at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich to teach drawing to cadets. It was (correctly) believed that instruction in the art of drawing would sharpen the observational skills of future artillery and engineer officers. Pownall’s comments echo this sentiment. This belief, and this pedagogy it demanded, would later be adopted into the curriculum at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

One might presume that because Claude Lorrain (1600-1692) predated Sandby and the others by more than a century, his work exerted a direct influence on their development. Given that no museums yet existed, the only direct access painters might have had to Claude’s work would have been via private collections. Claude’s Liber Veritatis—a kind of catalogue-raisonné of original compositions created by the artist, was known only to those in Georgian England with whom its owner, the Duke of Devonshire, chose to share it. One of these was John Boydell, who engaged printmaker Richard Earlom to reproduce all two hundred of Claude’s drawings in etching and mezzotint for their publication between 1774 and 1777. It is tempting to ponder the notion that the success of Scenographia Americana, published six years prior, helped convince the duke to share Claude’s Liber Veritatis with the world.

Claude Lorrain (1600-1682). A plate from the Liber Veritatis, engraved by Richard Earlom. From a later edition published in 1803 by John Boydell. Claude’s success as a landscape painter inspired legions of mediocre imitators. In order to protect his intellectual property, Claude documented his original compositions as ink drawings, sometimes with color accents. This he did from ca. 1635 until his death, referring to his catalogue of images as The Book of Truth or in Latin, Liber Veritatis.

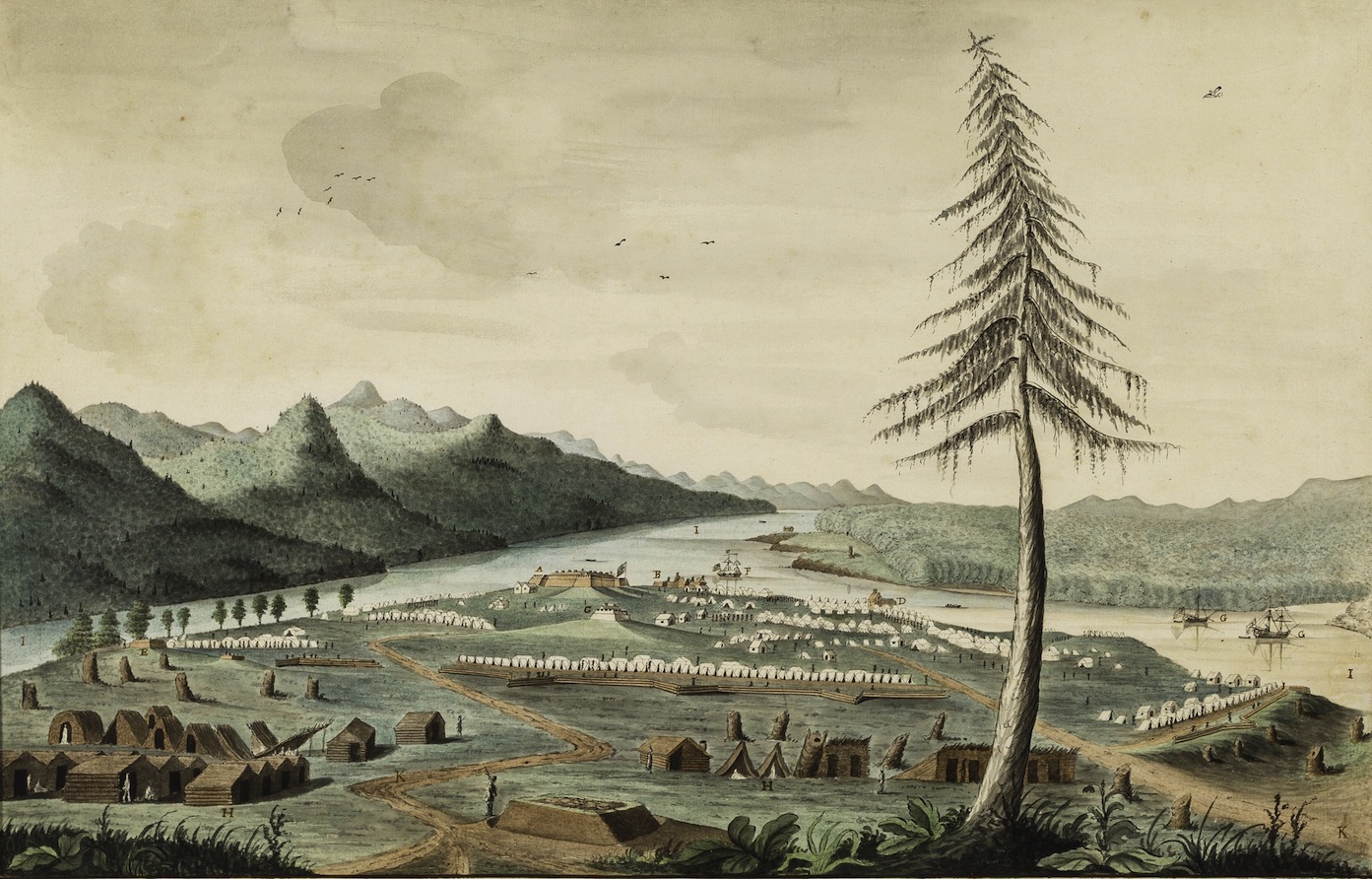

Thomas Davies. A South View of the New Fortress at Crown Point with the Camp commanded by Major General Jeffrey Amherst in the year 1759. Watercolor on paper. Collection Winterthur Museum, Delaware

Filtered through the landscape paintings of Richard Wilson (1713–1782), Paul Sandby, and his brother, Thomas Sandby (1728–1798), Claudian influence can be seen in the early works of British artillery officer Thomas Davies (1737–1812). His 1760 watercolor of the British forts and encampment at Crown Point, New York, aestheticizes what could have been little more than a diagram.

Thomas Davies. The Attack of Fort Washington . November 16, 1776. Watercolor on paper. Collections Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

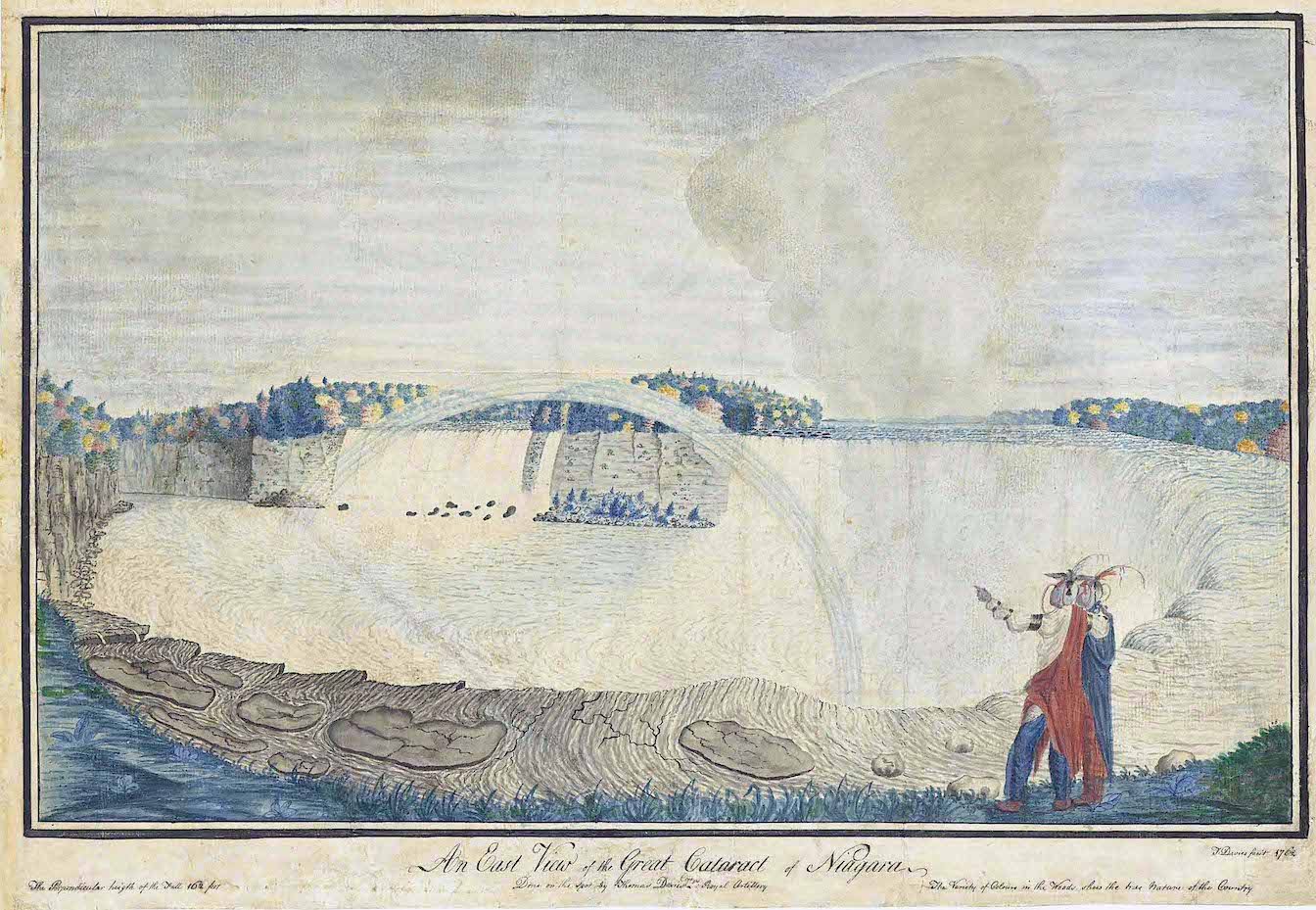

Davies’s view of the November 16, 1776, attack on Fort Washington in northern Manhattan expresses both topographical specificity and artistic élan. Davies is credited with being the first European to draw Niagara Falls from direct observation.

Thomas Davies. Niagara Falls. Watercolor on Paper. Collection National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

The visual language developed by the British military for topographical rendering provided some of the undergirding upon which the civilian artists J. R. Cozens, Thomas Girtin, and J. M. W. Turner built more poetic, creative visions of nature. The landed gentry eagerly decorated their dwellings with views of their rural estates, along with portraits of their horses, hounds, and wives. Like Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) and his brother James (1749–1831), the Scotsman Archibald Robertson (1765–1835) and his younger brother, Alexander (1772¬–1841), trained under Benjamin West and Sir Joshua Reynolds at the Royal Academy in London. Moving to New York in 1792, the brothers established the Columbian Academy on William Street in lower Manhattan. Touring the Hudson Valley in 1796, Alexander Robertson collected picturesque views along the river that were influenced by the British topographical tradition embodied by Richard Wilson, Thomas Gainsborough, and Cozens.

William Russell Birch and Thomas Birch. The City and Port of Philadelphia from Kensington. 1800

During the first decades of the nineteenth century, Philadelphia became the publishing capitol of the nation. Four years after Robertson’s Hudson Valley sojourn, the English-born artist William Russell Birch (1755–1834) engraved and published views of Philadelphia in multiple editions, the first of which appeared in 1800. A booming print culture soon flooded the American public with picturesque views of scenic attractions, from Virginia’s Natural Bridge and Lake Champlain to the falls at Cohoes, New York, and the Fairmount Water Works in Philadelphia. In the catalogue for her 2019 exhibition From the Schuylkill to the Hudson: Landscape in the Early Republic. Anna Marley writes, “Centrally located between the mighty Delaware and the picturesque Schuylkill . . . Philadelphia was defined and limited by those powerful borders. Images of these rivers not only embodied the ideals of the new American nation-state, but also led to the creation of the Hudson River School.”

Thomas Cole. View of Fort Putnam. Oil on Canvas. 1825. Collection Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The actual start-date for American landscape painting predates Thomas Cole by more than a century. Meeting a practical need for chorographic imagery to accompany topographical maps and nautical charts, scenographic drawings and paintings assisted in the visual recognition of landfalls, harbors and terrain, in much the same way as Jane’s silhouettes later identified warships and aircraft. Military topographical landscape sketches were elaborated for the print market by professional artists like Paul Sandby, who in turn delivered drawing instruction to future military officers. Proficiency in drawing enhanced reconnaissance skills, and thus the process of intelligence-gathering. Following the French and Indian War, popular demand for North American scenery increased. Images produced for military and scientific use were repurposed as etching and engravings, to be consumed by veterans of the Grand Tour, landowners and drawing-room pathfinders.

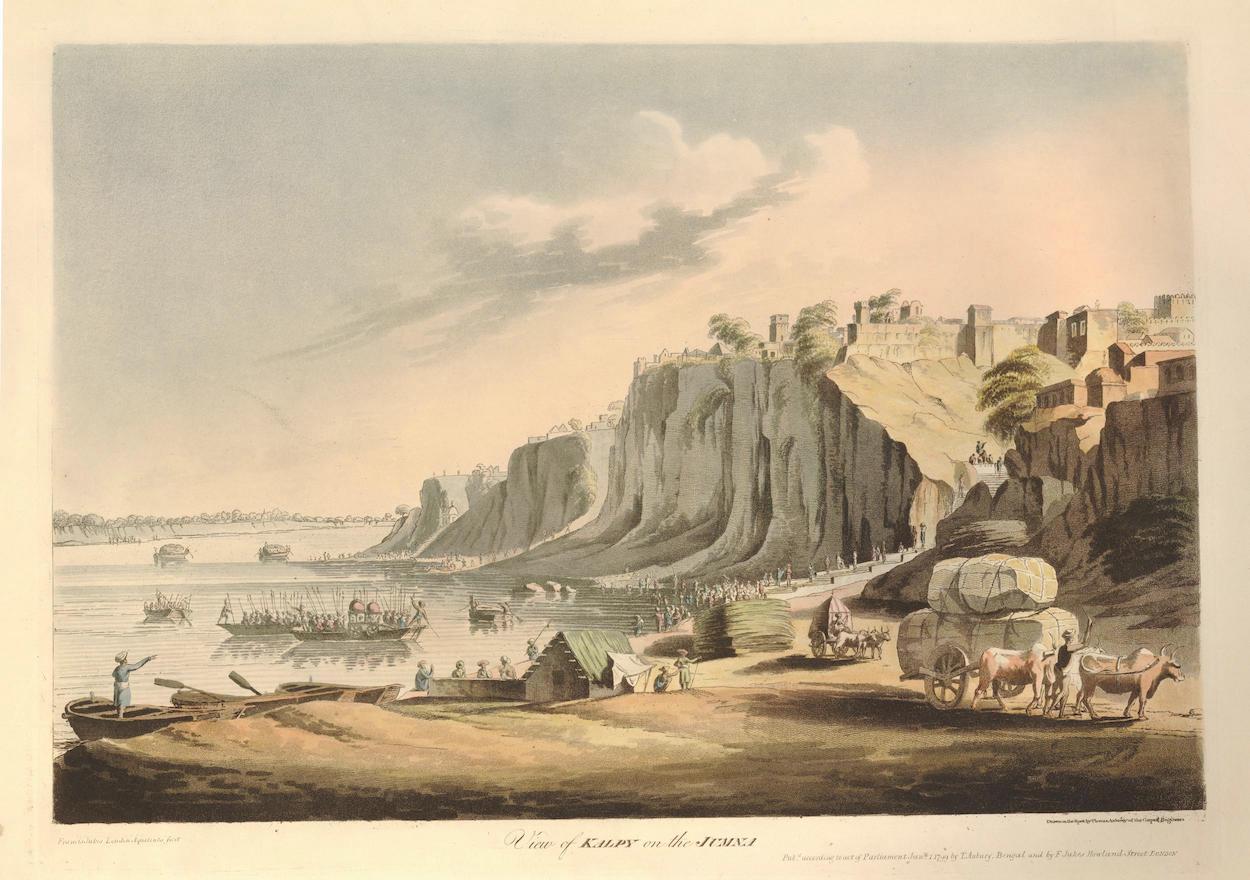

After Thomas Anburey (1759-1840). View of Kalpy on the Jumna. Francis Jukes. London, 1799. Collection of the British Museum.

(Thomas Anburey served as a lieutenant in the 47th (Lancashire) Regiment of Foot, during Burgoyne’s campaign of 1777. Taken prisoner at Saratoga, Anburey traveled to Cambridge Massachusetts, then to Charlottesville Virginia before returning to England in 1781. In 1789 he published as a series of letters an entertaining book Travels Through the Interior of North America, 1777-1781. Anburey’s keen observations and clever narrative has been called into question.)

Into this publishing boom enters Claude Lorrain’s Liber Veritatis in 1774, ninety-two years after the artist’s death, and one year after the Boston Tea-Party. Its publication exerted a major influence on both poetic artists and military topographers alike, by further defining their aesthetic goals. In the years following American independence, homegrown talent was joined by new arrivals, clamoring to celebrate the natural wonders of the new republic. The burgeoning print-culture became a melting-pot for professional artists, naturalists and geographers, having already put the American landscape on the map, many years before Thomas Cole made his first voyage up the Hudson River. As before, armchair wanderlust fueled popular demand for etchings and engravings of faraway places; visual travelogues described in a graphic language developed by mapmakers and military topographers. The American landscape-painting tradition was born not on an easel, but in sketchbooks carried in the field by explorers, naturalists and soldiers.

Download the essay Explorers, Naturalists and Military Precursors to the Hudson River School. in HUDSON RIVER VALLEY REVIEW. Volume 37, Number 2. Spring 2021

Now available to own: Sketchbook Traveler: Hudson Valley

Explore my Quaranteam Dispatches, from April 1-June 8, 2020

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Linkedin

Linkedin